The Up Drafts is an ongoing series of essays and interviews that examine creativity, productivity, writing process, and getting unstuck.

BY NANCY REDDY

I am writing this column from the passenger seat of my car, which is parked alongside a road deep in the snowy woods. I’ve dropped my kids off for two hours of outdoor camp at a wildlife center, and before I know it, it will be time to retrieve them. They’ll tell me all about the turkey vulture and the bald eagles and the blue jay (named Blueberry! my five year old yells over and over, to make sure he’s heard) and ask for snacks and complain about being too hot in their snow bibs and then too cold. But for now I’m trying to write.

This column has been hard to start. In the ongoing emergency of the pandemic and the long-term emergencies of systemic racism and gendered caregiving burdens, which have all highlighted in stark terms that time to write and even think are allocated unevenly, even writing the words “writing retreat” has made me a little nervous. With half a million Americans dead, it has sometimes felt frivolous to write about buying nice chocolate and writing goals on a white board. But also I believe that writing is vital, and that claiming space for writing is just as essential now as ever.

To think about how we might recreate some of the benefits of a retreat or residency, I spoke with three writers, all poets and parents, who have recently created at-home writing retreats. Chelsea B DesAutels, author of A Dangerous Place, forthcoming later this year from Sarabande, talked to me going on “retreat” while dogsitting for her parents. Twila Newey, author of Sylvia, created a one-week writing retreat in her own house. And Christen Noel Kaufmann, whose hybrid chapbook Notes to a Mother God was a winner of the Paper Nautilus Debut Chapbook Series and will be published this year, has declared each Friday her writing residency in her home.

All three writers talked about the significance of calling their time a retreat because it allowed them to claim it as a space for writing. Kaufmann wrote that “Calling it a residency/retreat is important to me because it lets the people around me – my husband and kids – see it as real time for work. I literally tell my children I’m going to work. It also helps me take it more seriously.” Similarly, Des Autels said, “Calling it a “residency” is actually kind of a big deal. First, it indicates to me that this is time I’m allowed separate from my other obligations, and that I am supposed to prioritize writing. Second, it indicates all of this to my family—they know I’m away to work.”

A few tips from these three writers, whether you’re looking to get away entirely or just carve out an hour or two one day a week:

Prepare your space and anticipate your needs

All three writers described physically arranging their space to prepare for writing.

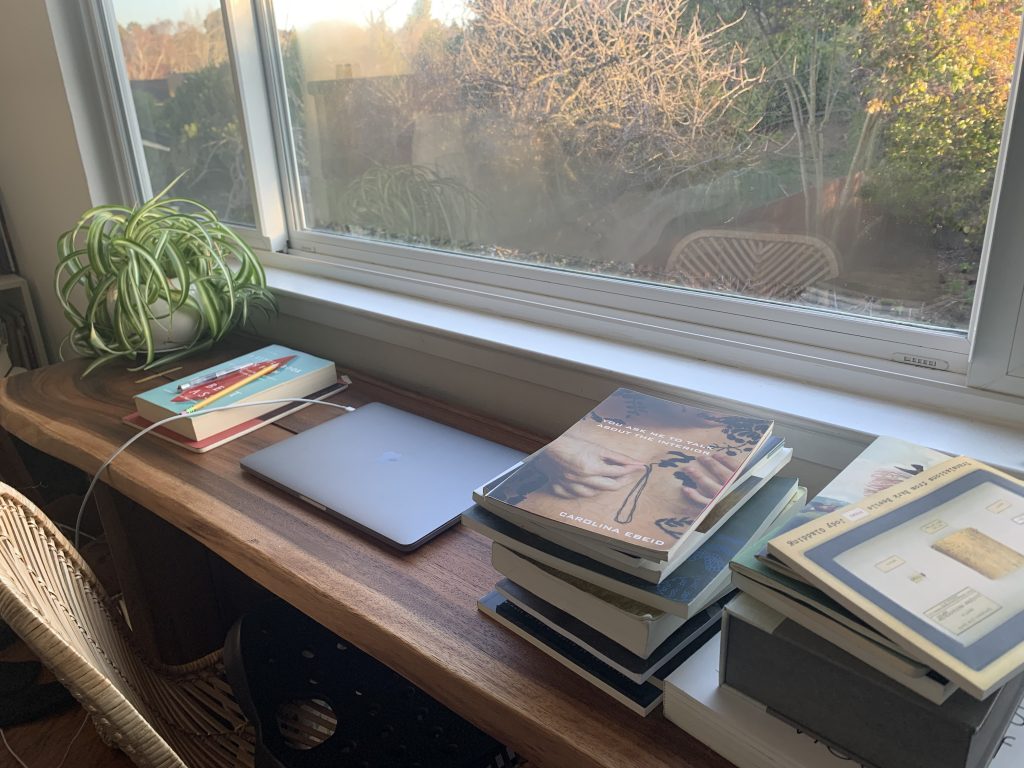

When DesAutels worked at her parents’ home, she wrote on a dining room table in front of windows overlooking a frozen lake. She says, “the first thing I did was clear off their table so that it was completely open, and then unloaded and organized my own work—laptop, notebooks, a few of the books I brought and knew I’d need to reference, folders with research and edits, and a candle.”

Though Kaufmann and Newey both described cleaning, Newey also granted that “maybe you work well in a cozy mess” and so she advises writers to “prepare your nest so you’re comfortable,” whether that means total tidiness or piles or something in between.

If you’re working at home, you may need to also proactively block out distractions. Newey, who was writing while at home with her husband and four children, wrote that “I recommend ear plugs or a pair of shooting range earmuffs if, like me, you can’t tune out your children’s complaints/arguments.” (She clarified that “I do not own a gun, just the earmuffs.”)

Define your goals for your retreat

DesAutels’s work was driven largely by the need to finish copyedits and write the acknowledgments for her book, so she was working with a clear task and deadline. Similarly, Kaufmann wrote a list of tasks and projects: “I usually make a list of what I want to accomplish and write it on the white board above my desk. That can be a certain number of poems written/revised, a word count, books read, or more administrative tasks that come with publishing.”

If defined goals feel too constricting, you might draft a menu of options. Newey wrote a big list of possible things to write and read, then selected a few from each list.

Establish a rhythm

DesAutels based her schedule on the one she’d used previously while at a month-long residency: “I planned to wake every morning at the same time, make French press coffee, and write early and for as long as I needed until I had a poem draft. Then I’d walk the dogs and eat lunch. I planned to spend my afternoons working on the other projects. I brought food that wouldn’t require much preparation. I planned to spend my evenings reading and revising.”

There’s a great conversation during the Commonplace episode on Macdowell about setting up a routine during a residency that includes several different poets’ approaches.

Give yourself credit for everything, including your rest

In writing about her retreat, Newey reminded me of the twin definitions of “retreat,” which both feel relevant now:

retreat: n. a quiet or secluded place in which one can rest and relax.

retreat: v. move back or withdraw. as from battle

She went on to say that “For me the week was also a rest from social expectations around production, publication, the scarcity model. My time to sink into the rich and generous space of creativity where there’s always more than enough or take a daily nap or leisurely walk or watch some t.v.” On the list of things she’d accomplished during her week Newey listed both finishing and submitting a chapbook and writing new poems and sleeping in until 8 or 9 AM and taking a walk each day. This feels like an important reminder that all of those activities can be part of the writing process.

Similarly, DesAutels wrote that, even though she hadn’t written as many poems as she’d planned during her time away, “I still count the residency as a success. I’ve had a hard time during the pandemic setting aside private time to write. The residency was so wonderfully quiet. I got to spend time in my own mind. And I read a lot more than I have in a long time. I might not have come home with as many new drafts as I’d wanted, but I came home with ideas and with a softer mind, and that’s a step in the right direction.”

More Resources

Several residencies have shifted some portion of their programming online, making parts of the residency experience available to writers working at home.The Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and the Vermont Studio Center have both launched virtual programs (Virtual VCCA and Virtual VSC, respectively) that aim to build community and celebrate fellows’ work. (The Virtual VSC event calendar for February, celebrating Black History month, looks bonkers good, with a lineup including a reading and a craft talk by Joy Priest, Tommye Blount and Nathan McClain in conversation, and a conversation about Kiese Laymon’s Heavy, among others; all events are free and open to the public.)

If you are looking to actually get away, Sundress Academy for the Arts is accepting applications for summer residencies through February 15th, with full and partial scholarships available for BIPOC writers and writers with financial need. Because the residency is so small – two people in the farmhouse and one more person at the coop up the hill – I think it would feel quite safe. Tin House is accepting applications for its residencies, which include programs specifically for writers working on a debut and for teachers, and weekend residencies for parents, through March 14. If you’re a parent, the Sustainable Arts Foundation’s list of residencies to which they’ve awarded grants in recent years to make them more accessible for parents can serve as a helpful starting point for residencies that might work for you, either by allowing you to bring your children or providing funds to offset the cost of childcare while you’re away.

I hope that, wherever you are in your writing and your writing life, you’re able to carve out some small space to feel like a writer, whether that’s a week or a weekend or a sliver of the morning before anyone else is awake. As Melissa Stephenson writes in her lovely essay, “Confetti Time,” “In the end, it doesn’t matter when or how the work got done. It matters that it did get done, one tiny piece at a time.”

NANCY REDDY is the author of Pocket Universe (LSU, 2022); Double Jinx (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a 2014 winner of the National Poetry Series; and Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018). She’s also co-editor, along with Emily Pérez, of The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood (UGA, 2022). Her poems have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Pleiades, Blackbird, Colorado Review, The Iowa Review, Smartish Pace and her essays have appeared in Poets & Writers, Electric Literature, Brevity, and elsewhere. The recipient of a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and grants from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Sustainable Arts Foundation, she teaches writing at Stockton University in New Jersey.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)