34 pages, $10.00

Review by Hannah Rodabaugh

Brandel France de Bravo’s poetry chapbook Mother, Loose combines childhood nursery rhymes and a sense of overwhelming grief into a fascinating, hybrid document. At times, it resembles the humor of the book Politically Correct Bedtime Stories—except this collection is more like its grown-up cousin than its twin. Other times, the collection is intense in its portrayal of the narrator’s dying mother—sometimes similar to Plath’s aesthetic-like immolation of her father. This chapbook’s lush language, its poignant grief, and its imaginative retelling of classic nursery rhymes are a delight to read.

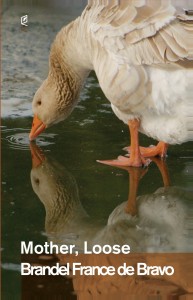

The title appears to be a sort of intersection: a play on the words “Mother Goose” and “Mother Lose.” This double meaning is intentional as so many of the poems, even the retold nursery rhymes, are about the death of the narrator’s mother (or at least a mother figure) from some form of cancer.

de Bravo suggests the intersection of these two mother figures in the poem “Mother, Tongue”:

“Here,” said the midwife guiding my hand,

and I caught, then brought the soft, slippery

weight, not covered in vernix but blood,

eye level. “It’s a liver,” I cried

before noticing my papoose’s papillae.I swaddled the slippery softness, my little

lingua, frankly feeling tender,

dare I say, iconic, golden

—Madonna, child, mother, tongue—

and cooing gosse like the one who

birthed me, French for baby goose.

References to tongues, language, and speaking blend naturally with motherhood and goose references. The poem seems to suggest that the figure of Mother Goose has birthed her linguistically—if not physically. But it’s the messiness—the bodiness—of the poem that really draws our attention. The poem is most compelling in its images of actual motherhood: its midwives, and vernix, and blood. Mother Goose, a mother figure from all our childhoods—perfect, incandescent, sterile—cannot hold up against the messiness of real life. There is always a point in any child’s development when we see our parents as fallible (or at least mortal) and cease to admire them as authority figures in the way that we once did. This poem, like many in this chapbook, seems to suggest this contrast—the contrast between how you view your parents as a child and how you view them as an adult.

While I was delighted by the nursery rhyme retellings—the author has a teenage Mary and little lamb shop at Victoria’s Secret and get their nails done—what stayed with me the most was de Bravo’s powerful witness to the narrator’s mother’s slow departure into death. For example, the poem “Ladybird Ladybird Fly Away Home Your House Is on Fire” has this beautiful sequence:

phone in my hand standing in the garden of

a house I no longer live in my mother says

“x-ray” her dry cough flowering unremarkable

except for its constancy walking less the year before

a winded valley surrounded by mountains until

the smokeless fingers grew bulbs (they called it

“clubbing”) sent smokeless signals “please”

I said “see someone”

It’s sad—and perhaps prototypical of losing a loved one—like listing the things we regret—but it stays with you. There’s a kind of edge to it—a kind of bright sharpness—like the colors you see when your eyelids are shut in a bright room.

However, bitter moments are not the only thing that this chapbook offers. One of the other delights of this collection is its wonderfully inventive language. For example, the poem “The Old Woman in the Shoe,” contains the lines:

For dinner I give them broth, shouting,

“Cup your hands. Them that’s got the will

knows not to mind the scald.”

I love the idea of this old woman giving a gritty, surly monologue about living in her boot. These three lines may seem simple, but they carry a lot of weight. After reading them, I get a sense of exactly what kind of person this character is. I can even imagine the tone of her voice: a sort of portly bar matron crossed with a Victorian street urchin.

Another favorite passage is this gorgeous section of “In the Arms of Morpheus III”:

Ushered past empty velvet

seats to a baritone boudoir

where everything transpires

—oxygen machine overture

gurgling in the pit—

through the wrong end

of an opera glass

in a distant spotlight.

An ebony bed, a cave

burning with flowers,

the wilted elm where dreams

hang

golden pupa.

Reading lush lines like “the wilted elm where dreams / hang / golden pupae” makes my mouth water. The pleasure of lines like these is their tactile sensations—they glitter like sunlight across water as I read them.

Mother, Loose can be sad and serious, or playful and whimsical. But its sense of urgency, almost like the driving rhythm of a Beethoven symphony, compels you to keep reading. You certainly don’t need to know the death of someone close to you, or even their absence, to react to its universal sentiment. Whoever you are, it touches you.

***

Hannah Rodabaugh received her MA from Miami University and her MFA from Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School. Her work was included in Flim Forum Press’ anthology: A Sing Economy. Her work has been published in Defenestration, Used Furniture Review, Palimpsest, Similar:Peaks::, Horse Less Press Review, Smoking Glue Gun, Drupe Fruits, and Nerve Lantern. Her chapbook, With Words: Verse in Concordance, is forthcoming from dancing girl press.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)