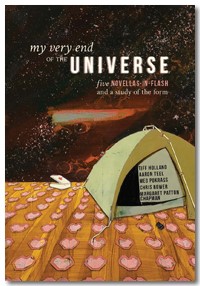

by Tiff Holland, Aaron Teel, Meg Pokrass, Chris Bower and Margaret Patton Chapman; Abigail Beckel and Kathleen Rooney, editors

306 pages, $15.95

Review by Jay Besemer

Chances are you’ve already heard of Rose Metal Press. You’ve probably also heard of the five authors contributing to Rose Metal’s latest anthology, My Very End of the Universe: Five Novellas-in-Flash and a Study of the Form. Like the press’s previous anthologies (and like the flash novella itself), it collects discrete prose packets into a unified, diverse, quirky whole. It’s like a good potluck; we get reacquainted with two Rose Metal Short Short Chapbook winners (Aaron Teel and Tiff Holland), and see fresh work by three other writers. Each author also provides an essay about his or her writing process. Highlights include Chris Bower’s wacky account of how a mechanical failure determined his working method, and Margaret Patton Chapman’s exploration of writing as cartography. All the authors’ comments are fascinating—far from the textbook-dry blah-blah one often gets in the context of studies of literary form. A great introduction by the editors also fills us in about the working nuances of the flash novella animal.

My Very End of the Universe refuses to reduce the genre to a generalized set of rules and characteristics. Each novella is a rule-breaker, each author something of an outlaw. Form and content are as idiosyncratic across the book as are plotlines. You’ll notice some common ground, though. Some of it’s formal; the flash novella highlights the tension between positive and negative space (transplanted from a visual to a fictional context) almost as keenly as poetry, and you can see this throughout each novella in various ways. Negative space in these texts tends to manifest either as absence or contrast—think of a black and white photograph, and how differently the negative is “read.” Curiously, these are all family dramas, playing on memory and pain as well as absurdity and love. The evoked situations are intense, as are the emotions brought up in the reading process. This is where the positive/negative space comes in handy. As Meg Pokrass suggests, we need those absences as much as we need the text. The conceptual space taken up by what isn’t shown provides relief from the more emotionally demanding things that are shown. Moving between contrasts, or from presence to absence, allows us to move through the story, taking it with us—and thereby assisting in its telling.

This is especially evident in the novellas by Chris Bower and Aaron Teel, though in very different ways. Teel’s work Shampoo Horns is a sort of pastoral grotesque in which startling brutality is balanced by equally startling depths of love:

She jumped up and dug under her bed, then pulled out an old Polaroid camera and aimed it at me. A whirring sound came from it, followed by the flash, blinding. We sat together with the developing picture between us, awed by its quiet magic. The picture caught me half turned away. She stuck it in her book, at the very end, then stood to put it back on the shelf. When she leaned over me a cross on a chain slipped free of her shirt and I touched it with my tongue. I thought wildly that Dad, sunburned and tired with his baseball and beer, had never done anything like that.

Here, we have negative space in its photographic sense of contrast and the play of light and dark, rather than a dance of absence and presence. What registers is the awkward tenderness of the scene, deeply contrasting the horrific banality of some of the other moments in the novella.

Chris Bower’s The Family Dogs is complex and potent, fragmented—even shattered—and condensed. Bower’s novella is the least narrative of all the novellas collected here. It’s easy to imagine some of these scenes actually taking place in a person’s life, though in slightly less tweaked versions. Here’s an entire flash segment from page 288:

Jewelry

When I was small Mom used to hold me in her palm, cupping me with her fingers. She didn’t have unusually large hands, I was just unusually small.

Dad used to say, ‘Don’t hold him like that. He’s not a piece of jewelry.’

‘Yes he is,” Mom said.

‘Can you wear him out to dinner?’ he asked.

Mom replied, ‘Will you take me out to dinner?’

And Dad said, ‘Fine, he’s a piece of jewelry.’

The fragmented, absurd, distorted and disjointed flashes comprising The Family Dogs actually resemble the experiences and perceptions of young children trying to process their world and their lives into a framework that more or less makes sense. Bower’s glimpses into the mysteries of life and death turn readers into kids peering into the View-Masters of our own past perceptions. Our role in telling the story is to be immersed in it this way—and to keep pressing the lever to advance the disc across the blank space into the next scene.

The flash novella is evolving into a potent form for use in telling 21st-century tales. Too intense and weird for longer, more commonplace prose genres, too complex and unresolvable to risk the temptation of cheap forced resolution in a short story, this sort of fiction makes for compelling reading that is as urgent for the reader as is its need to be written. I get the feeling that these authors did not necessarily write the works they wanted to write, but instead were granted the form to hold the stories they needed to write, or the ones that needed to be written: the ones we in turn need to read.

***

Jay Besemer is the author of A New Territory Sought (Moria) and Aster to Daylily (Damask Press). As Jen Besemer, he also authored Telephone (Brooklyn Arts Press), Quiet Vertical Movements (Beard of Bees) and Object with Man’s Face (Rain Taxi Ohm Editions). Jay is a teaching artist with Chicago’s Spudnik Press Cooperative and contributes critical essays to multiple publications.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)