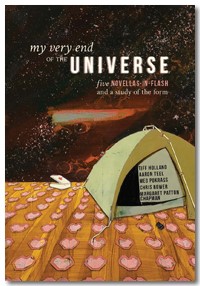

by Tiff Holland, Aaron Teel, Meg Pokrass, Chris Bower and Margaret Patton Chapman; Abigail Beckel and Kathleen Rooney, editors

306 pages, $15.95

Review by Jay Besemer

Chances are you’ve already heard of Rose Metal Press. You’ve probably also heard of the five authors contributing to Rose Metal’s latest anthology, My Very End of the Universe: Five Novellas-in-Flash and a Study of the Form. Like the press’s previous anthologies (and like the flash novella itself), it collects discrete prose packets into a unified, diverse, quirky whole. It’s like a good potluck; we get reacquainted with two Rose Metal Short Short Chapbook winners (Aaron Teel and Tiff Holland), and see fresh work by three other writers. Each author also provides an essay about his or her writing process. Highlights include Chris Bower’s wacky account of how a mechanical failure determined his working method, and Margaret Patton Chapman’s exploration of writing as cartography. All the authors’ comments are fascinating—far from the textbook-dry blah-blah one often gets in the context of studies of literary form. A great introduction by the editors also fills us in about the working nuances of the flash novella animal.

My Very End of the Universe refuses to reduce the genre to a generalized set of rules and characteristics. Each novella is a rule-breaker, each author something of an outlaw. Form and content are as idiosyncratic across the book as are plotlines. You’ll notice some common ground, though. Some of it’s formal; the flash novella highlights the tension between positive and negative space (transplanted from a visual to a fictional context) almost as keenly as poetry, and you can see this throughout each novella in various ways. Negative space in these texts tends to manifest either as absence or contrast—think of a black and white photograph, and how differently the negative is “read.” Curiously, these are all family dramas, playing on memory and pain as well as absurdity and love. The evoked situations are intense, as are the emotions brought up in the reading process. This is where the positive/negative space comes in handy. As Meg Pokrass suggests, we need those absences as much as we need the text. The conceptual space taken up by what isn’t shown provides relief from the more emotionally demanding things that are shown. Moving between contrasts, or from presence to absence, allows us to move through the story, taking it with us—and thereby assisting in its telling. Continue reading

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)