Archives

Night Shifts

The last time I saw Donnie, he got drunk on Lemon Lovers and I drove him to the Emerg. A drizzly, freezing-rain kind of night, and I work graveyards hauling laundry at the old base in Cornwallis-mess-hall scrubs in two kinds of marinade, big pallets of Air Cadets’ wet-dream sheets. Still, it beats the garbage truck, which I drove for three years until Ed, the fat foreman, found the recreational skirt and blouse I kept jammed under my seat. Brenda left me once I left Sanitation; she rented herself a basement apartment in town and enrolled in Medical Office Assisting. Took the cat and all her tarty V-necks with her. She never found out about my skirt and blouse, mind, and at least the laundry gig gives me free dental. Anyway, night shifts at the base are more private.

So I’m driving putrid sacks of old jock straps and Christ knows what else from barracks to barracks in my best Frenchy’s silk, when I get my 2 A.M. business call from Donnie.

“I’m sloshed, Uncle Hock!” he warbles proudly into the receiver, like after twenty and a half years of knowing the kid I haven’t learned to tell the damn difference. It’s those Lemon Lovers again, I know it. They’re this foul, cheap drink his girl Christine made up: mouthwash, lemonade, and a jigger of lemon extract. I couldn’t even drink one; he pounds six or seven, no trouble. I think of his liver and all I can picture is floor joists once termites have gnawed clean through them.

“You don’t say,” I tell him, cutting the steering so I don’t collide with the blue ruin of the former base chapel.

“Sure am,” he says, even slower than his usual; Brenda’s kid sister, Cheryl, was heavy into Cold and Sinus, so that should give you some idea. She took a stroke last April (Brenda found her swaddled in afghans and puke) so Donnie hasn’t got much family, poor numbskull, and Brenda hasn’t called him since the gong show at Thanksgiving. I guess you could say I’m his pater familias.

“So, yeah,” he says on the phone, even slower, and round about this time I remark that Donnie’s been wheezing real heavy, letting out little whinnies of pain the way our pit bull, Tank, used to do before we shot him. I veer left toward the old range, wait him out. I’m an old hand at Donnie and his cut-rate dramatics.

“I went and got myself stuck, Hock,” he says. The kid never was one for much exposition. I figure I’ll bite. I figure I’ll regret it.

“What do you mean, ‘stuck’, now, Donnie?” I ask him. Around Digby, Donnie’s become a bit infamous for getting himself Brigadoon-blotto and spending the night in a hospital bed. Like Thanksgiving, when they had to tweeze out the turkey wishbone he’d jammed into his left hand. Or July before last, when he went streaking at Mavillete Beach and turned out to be allergic to poison ivy. Welts all up his rump like a ridge of scales. So I figure either it’s his girl, Christine, or it’s some damn doctor thing, and either way I’m not an especially interested party at the moment, as the silk and pleated chiffon is tickling my ankles in a little sneeze of wind. I always crank the van windows down on the night shift, so I can feel my skirts blow around.

There’s a wild howl on the other end like a coyote giving birth.

“It’s-all them exotic fruits I bought,” he says.

The chittering idiot. Ever since Donnie got the mechanic’s job out at Pettipas Garage, he’s been ass-deep in kumquats and gaudy, greenish- pink dragonfruit, just because he can shell out for pricey grub.

“Did you try to eat them, for a change?” I asked him. “Instead of letting them moulder and get thrown to compost?”

“It ain’t that, Uncle Hock,” Donnie groans. “I been readin’.” Something in his gravedigger’s voice makes me careful. “It was an article,”-he keeps at it-“in GQ. About fruit and veggies, the things you can do with ’em. And it’s been fuckin’ forever since Christine-she’s a woman of morals, she says, and there’s certain things she just won’t…. anyways, it says there’s ways fruit can take care of it. Hollowed out, like, or halved. So this avocado…that’s what got stuck. Will you come help get it off?”

It’s my turn to groan; I’m a stag full of buckshot. It’s been almost a week since I was gussied up this much. I’ve missed my beige bra, my K-Mart pearls.

“I’m not leaving work in medias res to come pry an avocado off your dick,” I say.

“Well, will you drive me out to Emerg at six? The thing’s burnin’.”

“What about Christine? It’s more her department.”

“Can’t call her,” he says, like I’m totally thick. “Thinks it’s cheating.”

I can’t cook up a rebuttal to that; Brenda never knew about Mary Kay or Gloria Vanderbilt, either. Of course, I also never got my peter stuck.

I get off at six and there’s still a load of starched uniforms in the rear of the van for tomorrow night, so I figure I’ll suit up before I pick up Donnie in Flat Iron. He’s had the avocado on him for hours by now, and if he’s gotten into something else calamitous he’ll call back. To undo all the hooks and buttons on my chemise might take half an hour at least, so my safest bet’s to hide what I’m wearing. Lucky I’m a veteran at that.

At the Frenchy’s stores in Saulnierville and Meteghan (cluttered, fluorescent hodgepodges of used-rag bins and real French Acadians) I always go for earth tones and taupe. You pick the least conspicuous clothes so they charge you for garb from Men’s X-Large. All the better if you luck out with tops that stink of mothballs; it’s more believable that you picked them by mistake. I never liked shiny fabric much, anyway, and it used to drive me nuts when Brenda went shopping and carted home a car full of rhinestones and lace. Next, I go to the Men’s Coats rack and find something down-filled with really deep pockets, expensive enough to make up for the dress or whatever it is I’m about to pilfer. I bundle up the women’s stuff so small it could fit inside a purse if I wore one, and I cram it in the pocket of the coat I’ll buy. It helps that the fabric’s thin as tissue paper and feels like I’ll break it in my beefy hands.

I’m a do-gooder-I am, just look at Donnie-and it kills me that I have to steal every time. I’ve worked out a system to make amends- the coat has to cost twice as much as the dress, and then I donate it to a group home for the challenged. I’ve glimpsed the beneficiaries of my charity work around town: guys with Down’s Syndrome sporting too-long trenchcoats, or else unlikely hunters in their camouflage and feeding tubes. I like to think my moral compass still points Due North. I like to think that maybe it matters.

So I know what I’m doing when I hide a blouse. My plan is to find a chambray work shirt like the ones the cleaning staff (South Milford Scrubbers) wears, since it’s the only thing both broad enough to cover my shoulders and thick enough to hide the ruffles on my blouse. Luckily, I find one, and a pair of standard-issue navy-blue cadet slacks, a foot too short and looking more like capris with my hefty brown work boots beneath them. I tuck the frills of my skirt up inside an olive drab jacket, which I wrap deftly around my waist like a kimono sash. It’s almost enough to pass for usual.

When I pull up to Donnie’s trailer out in Flat Iron at six forty, he’s already crouched on the front stoop waiting. He has himself nestled in beside a rusty old Frigidaire to hide the offending appendage. Good job he never trucks anything to the dump.

“Thank Christ,” says Donnie when he sees my van. “It’s turned purple. How the shit are we gonna get me into the clinic? I can’t wear pants, Hock. I can’t hardly stand.”

I look down at my Air Cadet short pants, my South Milford Scrubbers blue button-up.

“I’ve got this, kid,” I say to Donnie, and I goose him on the shoulder the way dads do in Canadian Tire adverts. The front yard at Donnie’s place is a weedy mess, all wood chips and old bed frames and half-empty paint cans. I practically have to hoist him through it to get over to the van, where we unearth a Navy Blue Dress Jacket, large, to hold against his compromised crotch.

“Look at me!” Donnie giggles, still drunk. “I’m an Admiral!”

“You’re an ‘admirable’, all right, Donnie,” I tell him.

The drive to the outpatients in Digby is uneventful, unless you count Donnie yowling for mercy each time we hit a rut in the road. The Digby County Emergency Wellness Clinic is actually housed in an old Presbyterian manse, with extra wards built on as addendums when need or municipal make-work dictates. As is, it looks like a shabby Victorian with growths coming out in little rows. Even the hospital seems to have cancer.

Donnie and I manage to sidle up to it together, me bracing Donnie’s legs for support and propping him up so he doesn’t keel over. As we topple through the plate-glass front door I have the distinct impression we’ve swaggered into a saloon, abetted by Donnie’s alcohol breath. Saloons, however (I’ve watched my John Wayne) don’t come with hand sanitizer and Hep B pamphlets. They also don’t come with receptionists.

She’s lost a little weight since either of us have seen her last. Which is somewhat tragic, as there wasn’t much to lose and the effect is of a frightened sparrow atop a teetering birch. She can’t wear her tarty rhinestone V-necks or hoop earrings at a place of work (she must have graduated from Medical Office Assisting, by now) but she’s got this glittery, bug-eyed frog brooch on her mint-green hospital scrubs. The bitch.

“Good Mornin’, Aunt Brenda,” Donnie chirps, like he’s come to take her out for a donut at Tim’s.

“Name, Health card, and reason of visit,” she tells him, real businesslike, not meeting either of our eyes. He forks it over and tells her the information she already knows-his name-which she punches into a computer with glowing white words on a black background, like stars.

“Reason of visit,” Brenda repeats, unsmiling.

Donnie’s eyes tango all around the room-the TV blaring Tonka adverts, the patent-leather chairs, the Public Health posters. Suddenly his face clears, regal and rational, and for a second I almost believe he is an Admiral.

“I’m here for one of them PAP smears, Aunt Brenda,” says Donnie gravely, his head held high.

So if you see him around, will you tell him to call me? I have a down payment on a lean-to by the lake, and I think I’ll adopt a pit bull again. But I still work the graveyards-the restless graveyards- every night until six.

Sexual Abuse

Translated by Aaron Crippen

despairing I wandered the night

in despair

Little Brother come with me

a thin man in white with glasses

extended a sisterly hand

and woke me from my loneliness and pain

he took me to the Happiness Hotel

took my shadow

shrunken on a white bedsheet

the lights tearing gray memories

lights snuffing gray memories

lie in my arms, Little Brother!

here are a hundred spring kisses, Baby!

praise me-Little Angel

abuse me-Daddy!

rape me-my man!

scourge me-Brother!

ride my nude body

treat me like a con

I rode his back hard

I was limp but no tears with despairing claws I

followed his incoherent commands-

broke his thick myopia glasses

knocked out his gold teeth

beat him black and blue-

while he whimpered for Daddy and Mommy

I helplessly followed his commands

like a madman sleepwalking

with hard fingers on a beer bottle

I fucked his hairy ass

as the clock struck zero

his anus tore . . . he wailed like a newborn child

Two Poems

[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_12/Smith1.mp3″ text=”listen to this poem” dl=”0″]

Dear Mrs. Thompson,

Sorry if you ever tasted the salt of me

when you kiss your husband good morning.

I hope it didn’t taint your coffee

or make bloody murder of your lipstick.

I killed your marriage, and you

deserve to know that

he is not everything you prayed for,

but maybe his sweet kiss morning

is enough.

Dear Thompson,

Your ATM code is 9976.

Your family owns one Honda, one Ford,

all 3 of your children have bikes.

You have a fireplace,

3 copies of People magazine,

at the top of the stairs your children’s room is to the left,

the guest bed to the right,

your room straight ahead,

all your walls are white

like lies,

everything smells like lavender,

you have really nice sheets.

Dear Mrs. Thompson,

Your husband pays me 50 extra dollars

when I bust on his face,

25 more when I kiss him after.

I have never seen a man scrub so hard,

his skin red like the sin he’s trying to exfoliate.

He never brushes his teeth.

Can you taste his shame?

Did I bitter the back of your tongue?

Dear Mrs. The Bitch (as he calls you),

I imagine your scalp

adorned with 300 grey follicles,

one for every dead president

your man slaps on my chests,

his hand dragging until on the pillar he prays to.

I’m sorry for being holy to him.

Dear Mrs. Clueless

Sorry if I ever took food out of your children’s mouths.

If they have ever gone hungry

because your hubby feasted on me,

let me offer them the groceries I bought with his sacrifice.

Dear woman,

Have you ever wondered

why it takes him long to get dressed?

His outfit must be perfect and able to disguise.

He can’t leave the closet

until he can’t recognize himself.

Dear Mrs.,

When your husband tells you the bruises on his neck

are from bar fights, that’s my fault.

I have choked him twice.

Once because he asked me to.

The second time, he called me his nigger child

and I choked him.

Yes, I still came.

Yes, he came harder.

Yes, he paid me extra to apologize.

To Whom this may concern,

Have you ever fucked your husband

from behind?

I have, when he’s been a bad boy

cause it hurts him more,

but most of the time he is on his back,

he likes to rub my chest

while I gut him.

I wonder does he rub yours

when you are laying and open

and lied too.

Dear Ma’am,

You look lovely

in the pictures next to the bed

he turns face down.

Your smile bright as starry country night,

never let him cloud it.

Dear, Dear, Dear Sweet Woman,

I feel like we are family now.

I say this because I love you:

Caution the way his hips grind

and teeth part in his sleep.

Dear Mrs. Thompson,

I fuck your husband twice a week.

He pays me.

He is lying next to you.

Dear you,

He called me your name once, Ann.

I just thought you should know.

10 RentBoy Commandments or Then the white guy calls you a nigger,

[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_12/Smith2.mp3″ text=”listen to this poem” dl=”0″]

but not just any white guy, the one

who’s paying you, and not just any nigger,

but his little nigger child.(Never let a 50 dollar trick

do 100 dollar shit.)

You can’t deny he owns you

for at least as long as you are still

black and deep in the dark of him.

(Remember the terms discussed.)

So what do you know now? (If you failed

to discuss, know anything goes.)

You know he thinks of you

as a lion or AIDS or anything

scary and African to him.

(When anything goes, don’t panic.)

You know he thinks of you

as his son, which makes you scared

for his son, the thought that he could

want anything sweet to be this wild, wet,

and trenched in him. (Dazzled him,

even while dying inside him.)

He still called you a nigger,

but so what? You still gonna get paid.

(Respect or Groceries.)

You still gonna answer

next time he call. (this is money.)

You still broke? Still piss –on him– poor?

But you got clothes on your back,

brandy in your coffee mug. (Drink.)

Is it worth it to stop this history mucking

your skin if you ain’t you gonna eat?

(Pray soon.)

But this is all after thought,

it takes you ten seconds

longer than him to realize your hands

around his throat, ten more for you

to notice white mess on his stomach,

ten more for you to cum too.

(The customer must always leave satisfied.)

from Dick Strong

These excerpts from Dick Strong have been presented as a PDF to best preserve the author’s intentions.

The Wake She Leaves Like a Whirlpool

[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_12/Tansley.mp3″ text=”listen to this story” dl=”0″]

Something must have happened between then and now, here and there, because Imogen has been ignoring my smiles. It becomes clear I’ve done something wrong when she pulls my hand from the small of her back like a plug from a sink. I washed your hair earlier, I think; washed it clean of the gel and wax you use that leaves a damp film on my pillows and there are only so many times I can turn them over.

She plays with the snags of skin around her nails while we wait for our table. I drink Campari to pass the time and bang my knees on the glass front of the bar when I try to cross my legs. Perhaps tomorrow I’ll prove this with dark, blue bruises.

I ask her to delete the film she has of me on her phone, “it’s unflattering,” I say with a smirk, hoping to prick the tension, “I don’t like where it centres.”

Imogen runs a hand through her hair, pulling away loose threads. She stretches strands over the flame of a candle till they fizzle like a fuse and snap.

Victorian lamps and the film of cloud that lies over the city keeps me warm but in the shadow of the arches of the viaduct I notice the goosebumps on the parts of my skin that are exposed, hairs raised in anxiety since she walked out during dessert. Maybe by the time I get home, by the time I boil the kettle and fill the teapot, by the time she has decided to come home, I will know how to soak this all up, ring it all out.

There was a time when she gnawed my fingers, chewing an ache like growing pains into my bones. She liked to bite her way into the centre of attention, to carve an impression with her teeth. At parties she’d reach across conversations to leave little purple punctuations in my skin.

CrownGate shopping centre is full of the hulks of black and empty buses. She slept in one once, broke in and made a bed across a row of seats because coming home hard and angry wasn’t enough, she wanted me haunted. So I stand on tip toes, peer through the curved glass that makes a mockery of my face, looking for signs of her.

Imogen doesn’t have periods; she’s got an implant which stops them. It makes my pallor all the more noticeable when I get my own, when it feels as if my skin is being stretched. But my time of the month has become exhausting because of the weight of her. A pale film of desire and frustration settles over her round face. She is rampant; and crosses her fingers when they’re inside me.

As I cross the Severn Bridge I think I can see Imogen coming out of the hedged entrance of Cripplegate Park, but it’s not her. This woman isn’t walking slowly, holding her weight on each hip for long enough to think she might pause, for long enough to think she might sit down there and then like a child having a tantrum. The possibility of her, the rumour of her, is like the sweat that runs down a cold bottle of something, of beer, of water, of wine. And when she’s not here there’s not much else to say except that hopefully she’ll be back soon.

The street lamps cause a shimmer on the cling-film that covers my wrist and hand and I think again about how I’m going to get money out of my bag, sign my name if I need to, or go to the bathroom. My arm stays bent upwards, poised in the air, while the rest of me slides across the back seats of the black cab as it moves through the centre of town. Warmth comes in waves like cross words from the puckered skin. I should tell Imogen, tell her what happened. How the lid of the kettle, if you pour it like that, at the wrong angle, will fall open. How a blister can appear in an instant, needs no friction sometimes, but boils up from underneath. I take my phone out of my pocket but only check the time.

I’ll call her eventually. She won’t speak but I know she’ll cross herself. Not for me, but for the benefit of whoever is around. Two fingers touching the skin of her forehead, her chest, the left shoulder, and then the right. She’ll hang up and say, “needs her Imogen,” to whoever she’s with, but there’ll be time to finish her drink first. It will play out like a film; a chase down a hospital corridor, a reunion, a kiss. Her at the centre of it all.

Melanie and Edith

[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_12/Swide.mp3″ text=”listen to this story” dl=”0″]

The exotic fish were dead. Death should never come before noon. That skinny red headed guy who sold exotic fish told me to be careful, feed the fish regularly. He didn’t have faith in me. How could I go back to the fish store and tell him that I killed four of the fish? He would swear at me and call me names like fish-killer or give me that pathetic look like you left my motorcycle out in the rain.

The sun that shined through the windows dispersed my living room graveyard long enough for me to realize I needed a goldfish. My roommate was in Hawaii. I could borrow her gold fish and put it in the living room and then get my gold fish later before she came home. What if I mixed up the fish? Would she be able to tell? And then the phone rang. No one called me in the morning except for my best friend Edith.

“I am sleeping.” I said.

“I need to tell you something. Let’s have lunch.” She said.

She always had to tell me something.

I walked outside and the world looked flat and the sky was the color of the sidewalk and the two people on the street looked like two people on any street. There was nothing vivid about this day until Edith pulled up in her fancy car with her dark messy hair and her loud voice. She was in an orange vintage dress.

“Let’s take two cars.” I said.

We went to a swanky, outdoor shopping mall for lunch. The clouds above us were bland and we were with bland people; none of these people had ever been in Rome. I was fiddling with the menu and watching the waitress who had a hot ass. The restaurant was crowded. The air was stuffy. I wanted to get home to my one living fish Greta, who had survived the fish flu. My apartment rug needed to be vacuumed. My bottle of red henna hair dye was on the dining room table. I could have been a red head by now.

“You’re always so distracted.” Edith said.

“Well, you know.”

“I know what?” Edith asked.

“I told you big Connie at work has been on me. She’s going to get me laid off.”

“You’ve been at the same hospital for ten years, every week you tell me they are going to fire you.” Edith said.

“Well, this time it might happen. Connie mixed up the charts and blamed it on me.”

“You’re always so uptight. Jesus. Every day with you, it’s gloom and doom.”

“Yeah, well, you know.”

“You should really see a shrink.”

“That’s your news? you got me out of bed to tell me that?”

“You weren’t in bed, Melanie. And I really think you should start seeing a shrink, you’re not eating your lunch. It’s always paranoia and drama with you.”

She continued talking while I traveled inward to beatitude. I did this by envisioning her naked in a bath tub with a bunch of violets on her breasts. I didn’t like her lectures. Edith sounded like a group of bald congressmen when she gave advice. It was sickening, and the way her lips curled up annoyed me and her pithy statement about seeing a shrink felt like it was delivered to her on a silver dish by her handsome boyfriend Gary, who she might marry once her family determined whether his bloodline was royal or whether he was an impostor. Gary was delusional and thought he was a handsome prince from the Renaissance (he quoted Shakespeare) but he was really a common but arrogant jack-ass who didn’t know shit about how to make love to a woman.

Gary was an important doctor. Women fawned over him. He was a sucker for good looking women. Obviously this is why he was so smitten with Edith.

No doubt, Edith was someone to be admired. She was pretty in an unusual way. Her nose bent towards the Pacific Ocean. Her eyes were green. Her hair was dark, lavish, almost too much. She dressed up every day. And she was intelligent in that annoying way when a person really does know everything–how to tell what century a tree is from, the original mother myth of the knock-off myth, how swimming pools are professionally cleaned, how to make a soufflé, who sold what and to whom on the silk road, who wrote, The Doll’s House, (its praise and dissenting criticism), how opera singers become stars and how many calories there are in an air inflated rice cake. She was the head master of everything. And she insisted on getting a Brazilian bikini wax regularly. She was absolutely and without question a bitch to have as a best friend.

To make matters worse, a beautiful thoroughbred horse trotted behind Edith at all times. I had a humped back idiot that followed me around–an underling from a 1950’s Creature Feature. Edith wasn’t afraid of planes, of bees or of taxes. I was nervous and filled with doubt, but I had come to accept this about myself. We had different internal worlds. Who cares?

Apparently, she did.

We sat next to a suburban couple who blended into the wall. They seemed to be married because they ate their lunch without talking to each other and every once in a while the woman would ask the man a bland question like, “Didn’t I tell you that AT&T has cheaper rates?” And then she would ask another question without letting him answer the first question.

She was much younger than he was. She no doubt married him for his money. The man ignored his wife’s questions and asked her, “Did you find an acceptable accommodation for my mother and father when they fly out from Kansas?”

Edith and I had a bad habit of talking loudly when we were together. This couple was annoyed with us. The woman had platinum blonde hair worn in a retro bee-hive and she made a zip your lip signal at us.

I spoke louder. I winked at Edith and leaned into her close– taking in her oh-so-perfect beauty. This feeling I often had sitting next to Edith was like a rush of warm wind on Catalina Island. I went with it and took a risk.

“Remember that night we got drunk and French kissed?” I asked.

“Why must you always bring that up, Melanie? That was over 15 years ago. We were in college.”

“I bring it up all the time because I fell in love with you that night. I guess I wanted things to go further. I told you, you looked like a Russian princess.”

“You were reading too much Tolstoy at the time.”

“I was in a class entitled Tolstoy and His Works.”

“Well, that’s what I mean, you over focus on shit.”

“We could have been an item. I would have followed you to the ends of the earth, and I would have made better love to you than that stupid art history major Danny, you were so enamored with.”

“Shush, silly, I’m not gay and neither are you. You just like the dark poetry of it.”

“Are you in love with Gary?”

“I was. Not so much now, but we are getting married.”

Her voice got really loud when she said we are getting married. Like she was lost in the Amazon starving to death and her only chance of survival was screaming really loudly into the void we are getting married over and over again.

All of a sudden, I felt sick and Edith looked fuzzy and her beauty became invaluable just like when they auction fancy silver from the early 20th Century at Sotheby’s, gorgeous stuff that you would never need, but somehow your heart wants that silver telephone dialer, and some stuffy Vanderbilt holds up his sign and it’s over. I smiled. Big. Fake. With fangs.

Then I stuck my tongue out at Edith. “Gary is a fag”, I said in anger. I continued to talk crazy, it was painful to listen to myself talk crazy knowing that I did not mean anything that I was saying but I had to continue in this vein as if somehow this bland day had turned into some kind of airborne disease that I had caught from one of these bland suburbanite dweeb heads at the mall. I went on: “This is a prissy restaurant-the men need to get laid and the women need their rugs licked.”

Silence in the restaurant. All ears on us. You could hear a pin drop or a crab walk across the floor. The man sitting next to us (the one with the young wife with the retro-bee-hive hair-do) told us to shut-up and take it outside.

“Who are you? The Egyptian police? I asked.

I gave the evil eye to his wife who had told us to keep our voices down.

Edith grabbed my arm, “Please, stop.” She said weakly looking like a sick kitten.

I turned away from Edith and apologized to this couple, whose lunch was ruined by my broken heart. I had transferred my pent up hurt feelings about Edith to them. I tried to make reparations. “Please excuse my rude behavior. I have been in crisis ever since they took away my membership at the country club.”

“Please stop talking to us. Or we will get security.” The man said.

“And please stop talking loudly.” The wife said. She was stuck on that phrase. Please stop talking loudly. This was her favorite. She was not the sharpest knife in the kitchen. She never said lower your voice or I prefer quietude. It was always please stop talking loudly. (They didn’t seem to get that speaking quietly was something that would never happen if Edith and I were doing the talking.)

Edith stepped in and said “She’s off her medication and I am the social worker who is in charge of her care.”

I couldn’t let myself laugh at what Edith had just said. We are getting married kept exploding in my head. I got up and left her with the bill and I walked out of that bland mall with the bland people–my beloved Edith with her Gary and her upcoming wedding plans and I promised myself I would get on the crazy train and not stop until I felt like stopping.

Everything is set up before you are born–this little baby will grow up to be the boss from hell, this baby a beauty queen, this baby the bi-polar misfit that nobody likes and this little rosy-faced tot will be the one asshole in the House of Representatives that is singlehandedly holding up the health care bill from passing. It’s hopeless.

When I got to the mall garage, I realized I had forgotten where I was parked. Why does this shit always happen to me? I went floor to floor. Every fucking car was grey. How can that be? I was thirsty and hungry. Happy, well-hydrated, well fed people walked past me. I saw several couples who I’m sure would be engaged soon. I saw an older couple out to rekindle their romance. The man smelled like cigars and old books and the woman smelled of Indian bath salts. Two happy children, a brother and a sister, were throwing their stuffed animal teddy bears in the air. Their parents flashed their prideful parent smile at me. The whole world was happy. I was the last unhappy person on earth. In thirty years my bones would be found in the parking structure and some scientist would make a note in his scientific journal that these were unhappy bones.

That’s when I saw my brown chevy with the big, orange sunflower painted on its side door. I opened the car door and got in. I didn’t feel like driving home or going anywhere. I tried to lie down in the front seat but that was uncomfortable. The seat was stuck and would not go all the way back and it was stuffy in the car. I turned myself around, away from the steeling wheel, and I just sat there with the door open, thinking. I tried to lie down across the two front seats, that didn’t work either. Why did I wear red shoes? They looked funny hanging out of the car. My mind was full of wind and heat. Like a tumbleweed. I closed my eyes. And then I heard the voice of an angel. Or was it a dog barking? When you are lonely the voice of an angel and a dog barking are the same thing. You invent things. You have to.

“Melanie, Mel-get up! Get up!” The voice got louder. I felt as if I was at a football game. When I opened my eyes, I saw her fishy eyes, that perfect dimple in her right cheek and I could smell her cherry-scented toothpaste. She held out her hand.

“What about my car?” I asked.

“We will get your car later. You are in no condition to drive.” she said.

Edith drove like a bat on fire. I thought she would kill us. I begged her to slow down. She drove faster. Then everything turned Twilight Zone. Suddenly a topless dancer was inside Edith and she was rushing to get to her lucrative job at the bar dancing the poles. She was glowing. She was sparkling like a neon sign on a road side motel.

When we got to her street, she demanded that I stay in the car. She went inside. I watched a bird play on the telephone wire. He was tweeting and jumping. A junior Elvis Presley. Edith came back and told me to get out of the car.

“Why are you talking funny?” I asked her.

“You’re nuts.” She said with an attitude.

“And you are perfectly normal like Nurse Ratched.”

“Shut-up,” she said as she pushed me through her front door and grabbed my waist like a jail warden. We walked on her elegant Middle Eastern rug, over the safe blue threads and then made an abrupt right into her bedroom. She had laid down a white and grey Indian bedspread and had removed her throw pillows. Her windows were open.

“I don’t want to watch a movie,” I said.

“Shut- up,” She said.

Then she turned cold. Ice cold. It was Alaska in her room. Where were the polar bears? the ice huts? Jesus, it was cold in there. Then she told me to take off my clothes. “But it’s too cold,” I said.

“Shut-up,” She said. There it was again.

“Shut-up? Last week at the biker party you recited the last three pages of Ulysses.” I said.

“I did that for you.”

I felt guilty. Maybe if I hadn’t talked so much I would have been a contender. Gary might not have won. I was always riding Edith about this or that. I never let her breathe. I felt loud guilt. I had reduced sophisticated Edith to one phrase. I had conquered her in the same way Napoleon conquered Europe and the conquistadors conquered innocent Mexico.

The song bird that had been dancing happily on the telephone wire flew away. Something dreadful was about to happen. Edith pulled the bedroom curtain closed. Her skin was incandescent. She climbed on the bed and her breasts were perfect but I had forgotten how perfect they truly were and we were we were going to make love and I was scared. Edith put her hand on my thigh and I noticed that she had left her alligator shoes on. She looked exactly like Catherine Deneuve in Belle du Jour. She was that elegant. I was trouble and had forced this on her. How could I enjoy it? The whole situation was corrupt.

She kissed me on the lips and drove her tongue inside my mouth and it felt like a mermaid and I was transported. And then she took my breasts with her tongue and they collapsed and became hers and then she went down and swirled her tongue inside of me like small minnows fluttering and she rolled me over and did things and then turned me back over and did more things, countless things, things I would never tell you in the dark, and I begged her to stop but she kept going. I told her I was finished and she told me she wasn’t.

And when she decided she was, I asked her “Why?”

“It was a mercy fuck, Melanie,” She said.

“I forced this. Is our friendship over?”

“Is it? You’re always so in my face. You dwell on the same shit over and over again. It drives me crazy.”

“And you hold everything inside until you turn into monster bitch.”

I wondered if she was going to punch me in the face for saying that. She didn’t. And we gave each other that look that meant so many things that language can’t convey. A look that was built on years of friendship and seeing each other through every disappointment and blessing that life can bring and our respective memories stopped us from our verbal chess game and the automatic way we had grown accustomed to talking to each other. This sexy early evening became still, frozen. We looked into each other’s eyes and saw that they were the doorway to fifteen years ago, back to the time we walked across campus together under a large and heavy moon, just the two of us–both broken hearted because we had failed academically in some way, and Edith’s boyfriend had met some other girl, and my girlfriend had stabbed me in the back and then borrowed my car and didn’t even bother to pay her parking tickets that were in my name and I had got caught recently for stealing a dress at Bonwit Tellar’s on Newbury street and Edith had to bail me out of jail and I still remember how her hair smelled that evening like rotten pineapples and how I wanted to take her on the dewy grass on that golden October night and how she kept talking about boring things and stupid shit and gripes and complaints, and her family drama, and I was tired of listening to her, but I loved the sound of her voice. Her voice pierced the autumn night air like a sea-dragon’s tail and wiggled itself inside of my heart and my blood stream and Edith slipped in like that, without permission and she became my world. Her question put us back to the present and where we were right now. On her bed. Post-sex. And Edith, a bride-to-be.

“Remember that time you wore that stupid cat costume with the scraggly tail to the first frat party we went to together-and you saved me from sleeping with that chemist asshole, what was his name?” Edith asked.

“His name was Frank Steinway. I always had to take care of you.”

“That wasn’t his name. Steinway? That was the name of his piano.”

“No, that was the name of his overrated, underachieving cousin,” I said.

“Cousin? What are you talking about?” Edith asked.

“Don’t you remember? Whenever you slept with someone, you gave their penis a nickname. Often times it was derogatory. You were such a bitch, but of course, you had a string of handsome young men eager to stand in line to dance with you or to ask you out for dinner. Frank’s nickname for his you know what, was cousin.”

“I never gave his penis a name, cousin was someone else’s penis. I guess I was a slut right?” Edith asked.

“No, you were exploring your options. You worked hard.”

Edith laughed and I joined in, our laughter bound us together in bliss-just long enough to confirm how far apart we really were now, how easily deep abiding friendships can be broken and how our college romance had receded. The time in-between those years was lost time, broken time, unrepeatable time. There was a long silence between us that lasted until that pesky cat of hers got into a fight with the neighbor’s cat. Bang! The silence broke. The garbage can on the side of the house spilled over.

“What was that?”Edith asked.

“Your pesky cat,” I said.

We were like soldiers who had come back from war and our own homes seemed unfamiliar to us. And then I grabbed that stupid silk pillow behind her and put it over her face. This felt good. I wanted to keep going-to press harder. I let go. I put the pillow on the floor. The room smelled like Edith–her perfume, her laundry and her indifference. I stared at her Modigliani print. Love is dangerously close to hate I realized in that moment.

“I once had two cats. I named the black one Hate and the white one Love.” I said.

“You’re the only person in this world who can make me laugh.”

Edith pulled me towards her. I was tempted to retreat into her briar, to let her give me anything she offered. I pulled back this time. I didn’t let her kiss me. The light changed in her room. The world had turned gloomy. This turn of light felt tragic and vulnerable, like a newborn that might not make it to the next breath.

“You can’t purchase not being gay, Edith.”

“But I’m not gay. I’m not. I just love you.”

“You have a fucked up way of showing it.”

“Tell me a story,” she said.

I told Edith about my nervous tic. Every time my boss insults me, I need to show someone my tits. I’m not picky. It could be anyone. I just have to show someone my tits after he insults me and the sooner the better. Once it was an anesthesiologist at my job. We got on the elevator together and we both had proper elevator manners and then I said, my boss just insulted me and I need to show you something, and I lifted up my blouse and bra. Then the elevator door opened to the first floor and he asked me my first name and I gave it, and he got out and said, “It was nice riding with you, Melanie.” He said this politely like the way a grandfather thanks you for bringing him soup. Then he walked away. He was used to seeing body parts. No big deal for him.

“You made that up.” Edith said.

“I swear I did this. I did. I showed him my–”

“Equipment.” Edith said. And then she put her head on her pillow.

“I am going to sleep. Stay over.” She said.

I continued my story—

The last time it was the mailman. My boss had insulted me. I went home sick. And then I saw him. I ran outside, he reached out to hand me my mail and that’s when I did it.

“You’re fibbing.” Edith said.

“No, I swear, listen to me.” I continued on.

Then he started to deliver the mail later and later waiting for me to get home. One day I got angry. I went right up to him and told him that he was greedy, that the tit show was over and that he should deliver my mail like he delivers other people’s mail. I told him the story of how my father took me to the opera when I was five years old, just him and me and my brothers stayed home with my mother and my grandmother handmade me a fake fur coat for the event, and that I had no interest in men who worked for the government. I wanted a man who would take me to the opera, but not really, because I am gay and prefer women but if I wasn’t gay–and he ran back to his truck and I finished my story even though now no one was listening.

Edith was asleep. She looked like a sea shell. And this very bland day turned into a happy day, but I knew she was still going to marry dumb Gary, but sometimes life brings surprises and you wake up in Wyoming and the morning light looks like a church in an old, forgotten ghost town. And you enjoy the shadows of what was or could be.

I put my head down next to hers. Tomorrow, I would make Edith a cup of coffee and tell her about my new gold fish and about the fish tank–how it stunk like hell and then I would leave. Gary would take my place. Her breasts like butterflies in my mind.

Three Poems

Boycott trinity

[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_12/Rooney1.mp3″ text=”listen to this poem” dl=”0″]

Is it possible to be a man with a friend. To be a man about it. SHE licks my hand and what I give her is thusly sticky. SHE licks my hand and the whole sidewalk falls from the fervor. Man with a friend watches me or is me. My shady pinkness and sexless mystery. The will-it-stain question. Head-on-the-floor-or-ruined-against-the-door question. There is no chance of this but to be a man about it is to stink up anyway, so all parts of me quash the thought.

Now that this man has a friend the whole world is his friend and steppable. If I lay little rocks for her path HE knows they are his as all space is his and all time. All the time I am pleading with her to draw a bath – leave us hanging – be her own woman and a real woman – leave us – but I am that man – with no fingers.

Central to my manhood is separation. Maybe this is how it always is. But being a man means I like to be the unusual of any two. When there are three of us, which there are, yes, always, I impale myself on the triangle’s beautiful tip. Our triangle spins about with my weight and then it’s her turn.

Shaved birth trinity

[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_12/Rooney2.mp3″ text=”listen to this poem” dl=”0″]

When is a circle a smoothing

When it is lined in one

where are the parts that decenter it

tip tip last tip

Shaved me plots my lives out till they overlap

Shaved HE is a null set, self-sucking

SHE does not want to fit and doesn’t

burn on like broken, hoping us

I posit a circle that would unite all parts

so circulate the literature

stage a new threesome but no one

comes

On the now line SHE says I will never

flub her

HE sips the solid room closed

happy to be here and easing out

HE is my motoring hand while SHE slips

the noose

Knifed me ribbits till I’m smooth again

A bad circle and perfect one

rocks its energy from harder

bone. In a circle where is the home.

Shape sifter trinity

[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_12/Rooney3.mp3″ text=”listen to this poem” dl=”0″]

My heart is a triangle. It has been said. But what type. HE is one side and narrow. SHE is a little less stationary. WE are all of us watching the spin. Which way will we drip next. Long sheets of water slack our sides tryingly. Trine, we are a bit thicker. But where does this width lead, to what does it lend its lecher spear. Gross on the floor SHE slips up, calls me Daddy. HE has no such ink or spill, but when our little room rocks oh we are pasty with it. I lace my wishes in such papery tricks that even I cannot tell the sides apart. Apart from this of course there is another shape, one that is not at all triangular. The shape is inside me, stoutly. In its sanded down edges are pieces of pieces. Years flake off in the shape of flakes. Said shape says we could continue and it says we could not. Rounds and bulbs later WE are all of us still and sticky, are all of us still stuck: HIS lever lengthening my compartment, my plumping spoon newly buttered against HER skin. This aside we are mostly thin. And so the nameless shapes grope mopily on, depressed in something lower than mud and muckier. A severer dance I have never severed. That triangle wanted to wear me into weather.

Three Poems

he gay

[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_12/Seth1.mp3″ text=”listen to this poem” dl=”0″]

my tum has bage in it – a seedy kind.

but it’s fine, my big slick cuz slobs all time:

pretz, peppy, sweet tat fries. no, teddy, you

can’t tag him, he’s my shined bargain find. true,

once chewed tushy takes on pooh. eww? ooh? well,

no b.b.g. gon’ stun holey less spells

swell in cuz’s dome. hallo? knock? any there?

yes, cuz’s sports bra is — his wearable care.

he kissy lick it. mommy say he gay –

he’ll aids. ok! can i sucky his cake?

sports bra fat

[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_12/Seth3.mp3″ text=”listen to this poem” dl=”0″]

teddy’s fallen in bed crack. is he dead?

i can’t reply: unc wants me to be fed.

teddy, teddy – bye! cuz hi. i like specs,

i like eyes. oh, warm chicky – this is heck

for mommy: she won’t shove in tum, she’ll soup.

but cuz will chicky: he’ll slurp till doo-doo.

why aunt let him stroke sports bra in mid feast?

ain’t it beast? mommy’s keyed: she spoons peas.

cuz no sucky cake if you’re sports bra fat.

these no mean, no bad. where’s yo baseball bat?

laser on

[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_12/Seth2.mp3″ text=”listen to this poem” dl=”0″]

cuz wants to tape sports bra ten till midnight.

it’s sore sight. teddy bear, are you all right

in crack? how’s your back? oh, it’s fine; that’s great.

do ya think i should taste cuz’s gatorade?

it may be straw, lem, or blue? i hope blue;

then it’ll morph cheek insides berry crude.

hmm, a dumpster mouth – home to zero blouse.

i want his rub in tum, but sport bra’s louse:

it steals eyes when eyes should laser on me.

there’s no suge in sport’s bra – no wee disease.

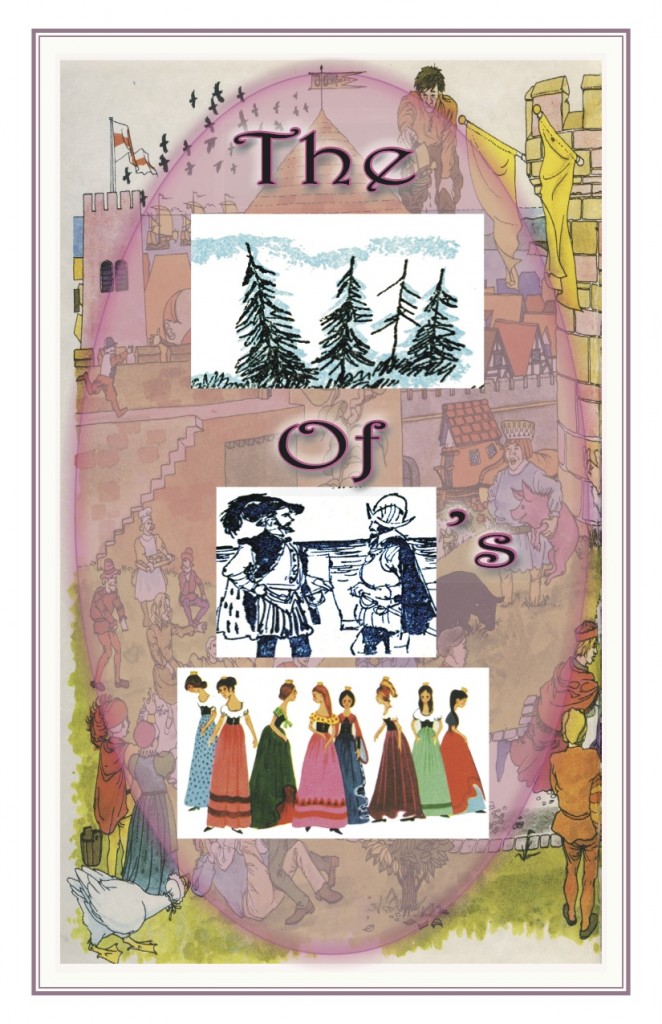

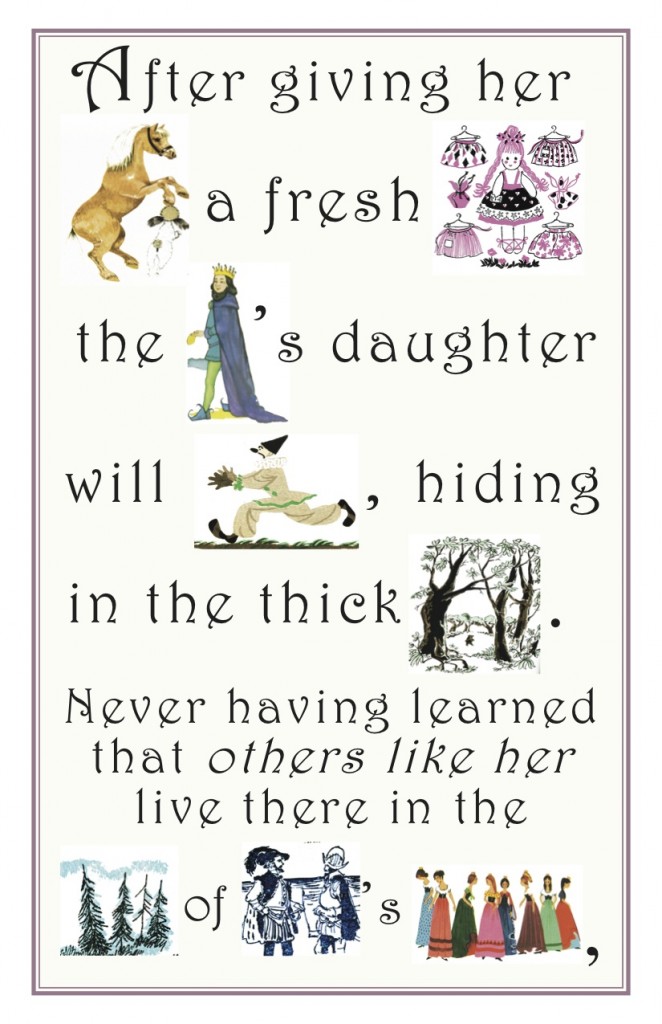

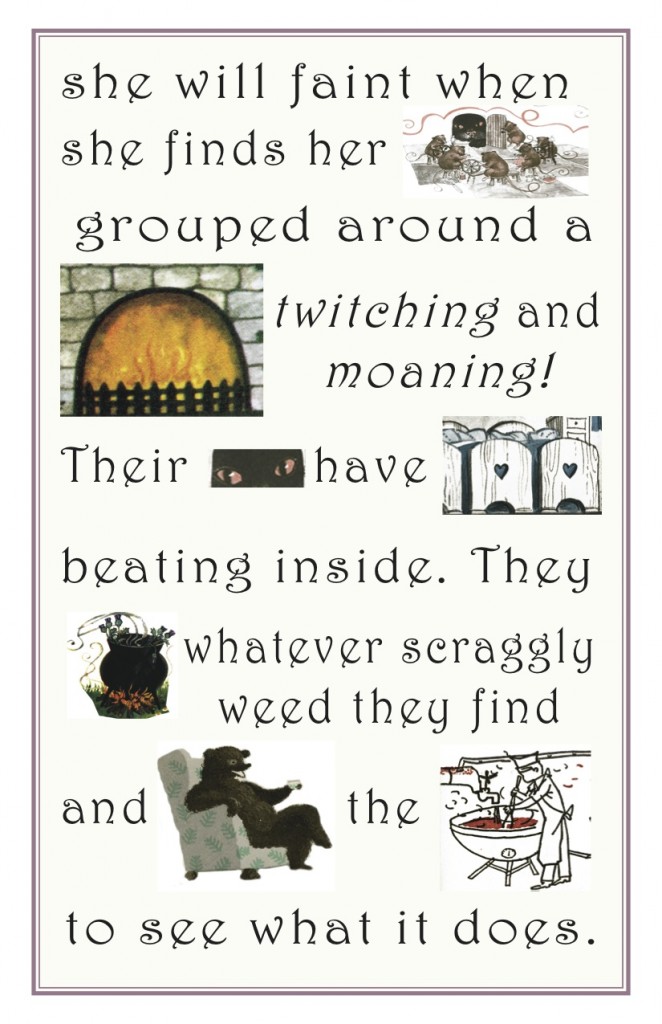

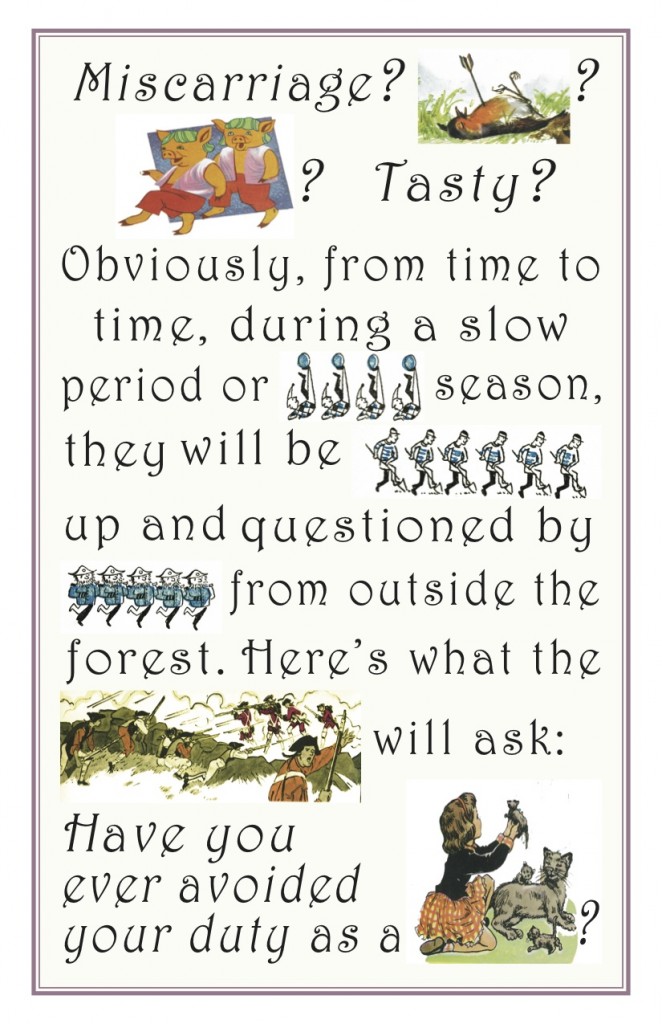

The Enchanted Historical Realm

In order to preserve the author’s formatting, this piece is presented as a PDF.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)