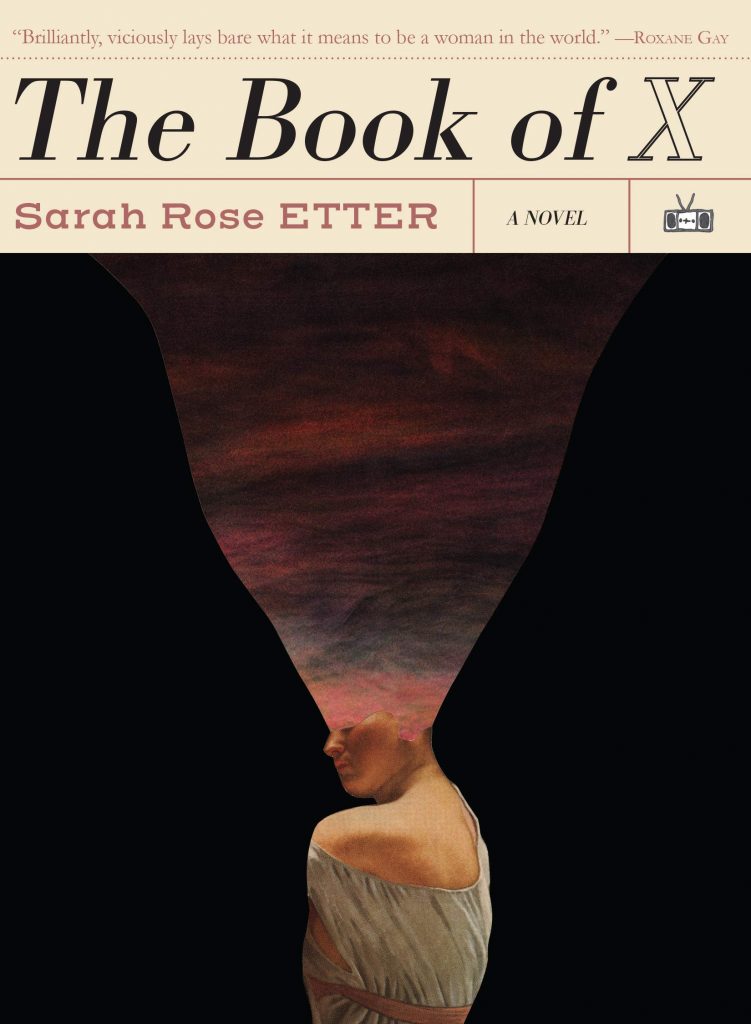

Two Dollar Radio, 2019

—

REVIEW BY GABINO IGLESIAS

Sarah Rose Etter’s The Book of X is a strangely poetic, heartfelt, dark, and wonderfully creepy exploration of womanhood dipped in surrealism and wrapped in a bizarre love story where physicality plays a central role. Packed with writing that inhabits the interstitial place between horror, literary fiction, science fiction, and dark fantasy, The Book of X is a unique narrative that pushes against the boundaries of the genres it draws from while simultaneously carving a new space for itself in contemporary fiction.

Cassie, like her mother before her, was born with her stomach twisted in the shape of a knot. Despite the deformity, she spends a somewhat normal childhood with her parents and older brother on the family meat farm. She usually stays home with mom while her father and brother go to the farm to rip chunks of flesh from the earth to sell at the market. When Cassie starts going to school, her life is sometimes disrupted by people who discover her physical abnormality. Cassie grows up and learns that finding a boyfriend and making friends are no easy tasks when your body is considered grotesque by most people. After surviving school, she leaves home and moves to the city where she finds a desk job. While living in the city, Cassie meets a few men, but it never works out. Meanwhile, the knot in her abdomen starts causing her pain and she begins to visit various doctors in hopes of finding a solution. The struggles with her body seem to be a physical manifestation of the struggles she is forced to face in her new life. Her boss is abusive, the city is depressing, and her family is far from perfect. The meat from the farm brings less money every day and her parents’ aging becomes obvious to her. Finally, her father dies and that sends her back home. Her return to the farm, an experimental surgery, and a new man who enters Cassie’s life under less than ideal circumstances force her to reconsider her life as she learns to enjoy imperfect love and comes to terms with her identity and body.

Etter created a unique world in The Book of X. Most of the narrative deals with everyday events like going to school, going to work, financial woes, a rough mother, and coping with rejection and depression. On the other hand, the story is infused with surreal elements?a store that sells men, meat farming, strange medical procedures?that somehow make perfect sense within the context of the story. Reality and weirdness inhabit the same spaces effortlessly and without clashing against each other. The result is a novel with a gloomy, depressive core that is also somehow hauntingly beautiful and wildly entertaining in its strangeness.

While this novel is unique and Etter’s voice is entirely her own, there were passages that reminded me of a variety of works, all of which are among my favorites. For example, the combination of sadness and strangeness brought to mind the novels of Alejandro Jodorowsky. Also, the book features short chapters made up entirely of dark imagery, strange visions, and nightmares that haunt Cassie. These passages are strong enough to cause discomfort in the reader. Also, they reminded me of the bizarre sense of discomfort and fascination I always feel while watching Begotten, an American experimental film written, produced, edited, and directed by E. Elias Merhige that has no dialogue and is entirely made up of dark, gruesome, religious, disturbing imagery:

“He opens the lid wider. More light creeps into the box, and I can see bodies slithering beneath the water, slick, scaled. Suddenly, a small face comes into view beneath the surface: two eyes, strange nose, a mouth.”

While the darkness that permeates The Book of X is one of its most powerful elements, the narrative is also infused with poetry that comes at the reader unexpectedly, kind of like finding a gem while looking for lost papers in a dumpster. That said, the poetry is also imbued with an unrelenting melancholy that crawls into your chest and refuses to let go, settling between your ribs and camping out for a few days:

“My throat is so full of love and sorrow that no more words come out. I can’t breathe and I know nothing, looking into the heart of the future, the relentless oncoming of death.”

Etter is a talented storyteller and The Book of X is proof of that. This is a book that is many things at once. On the surface, it is a narrative that explores a disfigured woman’s life and how cruelty and adverse reactions to those who are different are at the core of humanity. However, just under the surface, it is a sorrowful story about a lonely woman whose biggest wishes are to achieve some degree of normalcy in a world that has shown her how ugly normal can be and a look at the ways in which our nature as social animals drives us to relentlessly pursue companionship even when doing so repeatedly leads to suffering and rejection.

“In the afternoon, I read a book on the couch. I can barely catch the sentences, I can only imagine Henry’s lips, the history of the entire world in a kiss various genealogies of flowers blooming each time our mouths touched, how first I smelled lilac, then rose, then hyacinth, wet from the garden.”

The Book of X shines because it brilliantly enters into multiple conversations with various genres and shows how writers can use elements from whichever genre they please while respecting the rules of none of them. Etter’s many conversations, and the way she creates something entirely new, effortlessly bridge the gap between bizarro fiction, surrealism, horror, literary fiction, and noir without ever adopting any of their limitations. Furthermore, all of it happens while she creates a delightful dark and brutally honest narrative that shows what it means to be a woman in the world and that explores the ways in which what we are is brutally and/or tenderly shaped by the way others perceive us. In a way, this is a book created to expand the canon of what can be considered feminist literature, but it is also a celebration of storytelling that proves making up your own rules is sometimes the best way to create something unique and memorable.

—

GABINO IGLESIAS is a writer, journalist and book reviewer living in Austin, Texas. He is the author of Zero Saints and Coyote Songs. He is the book review editor for PANK Magazine and a columnist at LitReactor. You can find him on Twitter at @Gabino_Iglesias.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)