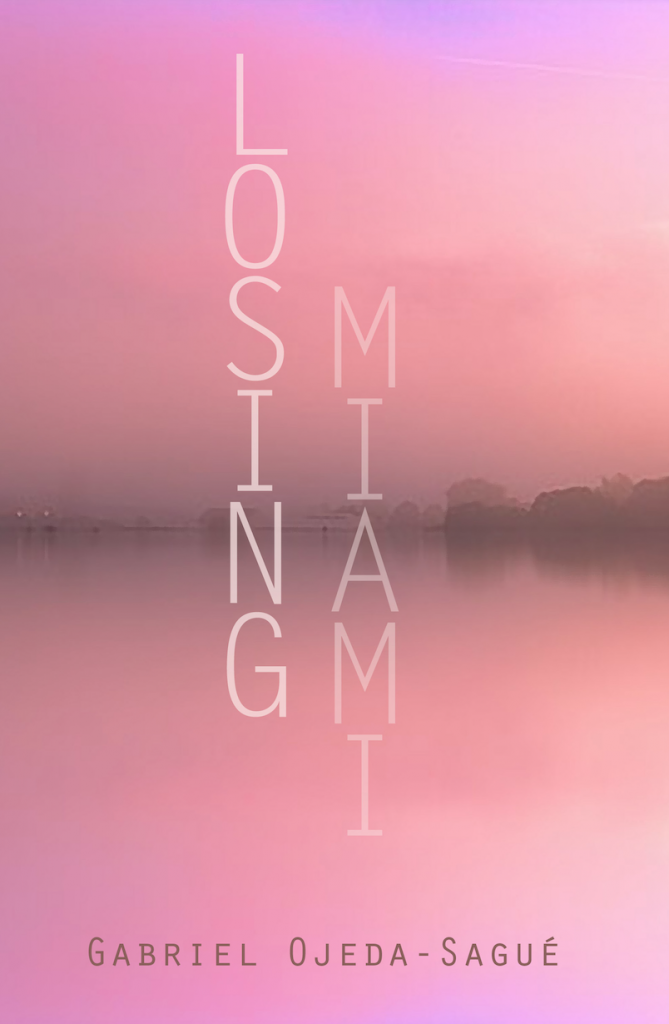

(The Accomplices, 2019)

REVIEW BY GABINO IGLESIAS

—

Gabriel Ojeda-Sagué’s Losing Miami is an outstanding exploration of exile, Otherness, and the possibility of returning to a place you’ve never been to. Unapologetically bilingual and packed with explosions of language in which coherence is ignored and the reader is invited to make connections between words, this poetry collection is at once brave, nostalgic, and passionate.

Ojeda-Sagué is fully aware of his status as a displaced person. His Otherness, like that of many others, make him a permanent nomad, someone who belongs only to movement and transitional/interstitial spaces. The same applies to his family, which came from Cuba. His work reflects that. Much like Gloria Anzaldua’s mestiza, the poet and his family live surrounded by the idea of a return to a place that never was or that could never be again:

I am asked if I would go to Cuba now that policies

have changed. When I ask my abuela the same

question, exchanging “irías” for “volverías,” she says

que “no tengo nada que hacer en Cuba.” Somehow,

I feel the same, even if I could never say “volvería”

because I have never been to Cuba. Returning would

not be the form, in my case. But to grow up in Miami,

as the child of exiles, is to always be “returning” to

Cuba. Everything has a fragrant—not aftertaste,

but third taste—of Cuba. Angel Dominguez writes

“What is the function of writing? To return (home)”

but his gambit is that the flight (home) is the writing,

the verb “to return” is the writing, not the home itself

or returning to it. What is the function of writing:

“to return.” The answer is no, I would not go to Cuba,

because the Cuba I come from only can be returned

to in the murmurs of the exile.

Ojeda-Sagué is a very talented poet, but the most beautiful element of Losing Miami is the code switching. Anyone who follows my work knows I love bilingual writing, and Losing Miami is full of it. The poet cambia de idioma de momento, sin perdir permiso a nadie y sin preocuparse por hacer que los lectores que no entienden el idioma lo puedan entender. This gives the collection an undeniable sense of authenticity and a cultural depth that few of its contemporaries share. Whole poems are written in Spanish without translation. They aren’t italicized or explained. They are what they are in a language that isn’t foreign; it is the poet’s language. Here’s “Esponja”:

el internet me hace sentir horrible, como si

todo pasara a la misma vez, y como si hubiera 30

horas en el día / casco del demonio / ciruela /

avenidas y malas noticias / dominó / dibujo el

mundo sobre un papel / duermo adentro del congelador /

encuentro parte de un radio en el patio / lo siembro /

allí crece un manicomio / azul y marrón /

en seis semanas / azul y marrón /

ciruela / una uva entre los labios de Patroclo /

en seis semanas todas estas ideas

serán ahogadas / serán fluidas /

al dibujo le añado agua de una esponja

While the poems in Spanish can be hard to decoded for those who don’t know the language, they are relatively simple and will not offer much of a challenge for those who opt to translate them. However, there are other poems in which Spanish and English share space that are not that easy to decipher. Ojeda-Sagué writes rhythmic clusters of words that act like a celebration of language, a bridge between cultures, and an invitation to fill in the blanks. These don’t appear early on. Instead, they show up once the reader has an idea of how the poet’s brain works. They are fun to read. They are intriguing. They tell tiny single-word stories and sometimes add up to bigger, multilayered narratives. Readers should slow down when they encounter them. These poems demand to be read twice, to be explored, to morph into new realities in the brains of those who read them. Here’s my favorite one:

sincrética allowance pájaro steak dar

criminal coraje water tendida field debajo

salted mar virus sigue giant carabela city

palma awful infección girls abierta bluer

grama palms sudan rafter mariquita heat

boca agape el great mosquito summons

coraje and viento acid pueblo gridlines

pobreza dreaming Haití they mandan

back queman back pobreza back abierta

back rezo that no take mi sweet vida back

If Losing Miami is any indication of what The Accomplices are going to be publishing, then do yourself a favor and put them on your radar immediately. The strength of this book sent me looking for more of Ojeda-Sagué’s work. It will do the same for you.

—

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, book critic, and professor living in Austin, TX. He is the author of ZERO SAINTS and COYOTE SONGS. His work has been translated into four languages, optioned for film, and nominated to the Wonderland Book Award, the Bram Stoker Award, and the Locus Award. His literary criticism appears regularly in venues like NPR, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Criminal Element, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. His nonfiction has been published in The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and other print and online venues. He was a juror for the 2018 Shirley Jackson Awards and the 2019 Splatterpunk Awards. He is the book reviews editor for PANK Magazine and a literary columnist for LitReactor and CLASH Media. You can find him on Twitter at @Gabino_Iglesias.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)