We wanted the holiday bustle to settle before sharing this wonderful story by Divya Mehrish for our November Future Friday! It’s our first prose piece of the series!

Divya Mehrish is a high school senior from New York. Her work has been commended by the Foyle Young Poets of the Year Award and the Scholastic Writing Awards, which named her a recipient of National Gold and Silver Medals. Her work has been published in the Ricochet Review, the Tulane Review, Body Without Organs, and Amtrak’s magazine The National.

Snapshot

We keep leather-bound photo albums on the bookshelves. Dust slithers over the front covers, reminding us to read our memories like encyclopedias, to search for the definitions of who we could have been. My mother has stacked them onto the shelf at the back of the living room, behind the piano no one plays anymore. On some Sunday mornings, as her espresso whistles on the stove, she sits at the dining table, her baby blue bathrobe draped over her narrow shoulders. She leafs through the books, her eyes wide. It’s my first birthday again. The pale pink cotton of the little embroidered dress wafts over my body, the body my mother had forged with her own hands, her own thighs, her own breasts. As I sip on my orange juice and try to balance redox reactions on the tablecloth, I watch her out of the corner of my eye. Her eyelids are fluttering, her face changing. One moment, her lips part to reveal her small jaw of beautiful, straight teeth. The next moment, she is gnawing at her lips, little vermillion carnations bursting in the thin line separating each half of her smile. Briny drops the size of the dew clinging to the petals on the terrace flow down the concaves of her cheeks. My mother never could hold back tears.

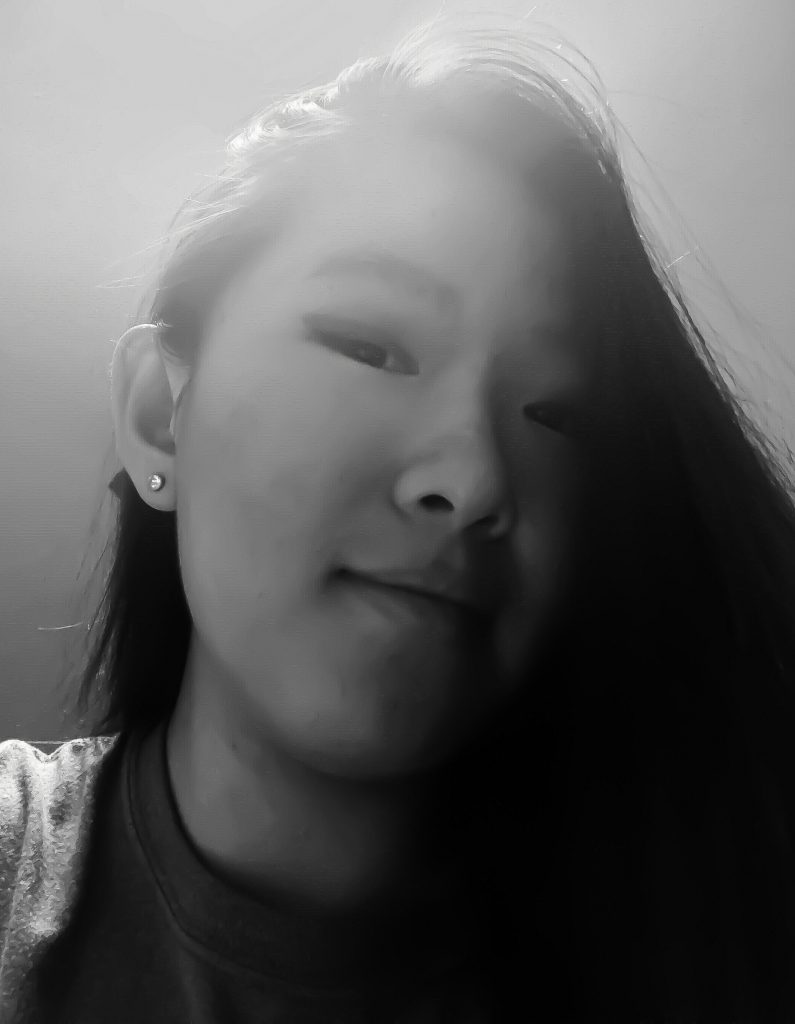

She leans over to me, holding the book in her arms like a sleeping infant. “Divya, look—this was your first birthday.” My gaze flutters over to the image. My hair is thick, dark, soft—raven feathers humming at my shoulders. It seems that I had my mother’s hair, once. Little gold bangles suffocate my fat little wrists. I am holding onto the pole in the playground for balance. I must not have been able to walk properly yet. My first two little teeth are showing, peeking out behind my moist, plushy upper lip.

I don’t look at my mother. I refuse to engage. I swallow the growing lump in my throat. I don’t remember that girl, but I miss her. I bite the inside of my cheek until I can taste metal stinging my teeth, rotting my gums. My mother’s fingers are stroking the waxy paper the same way she caresses our goldendoodle’s flaxen curls. “Weren’t you so sweet? Look how happy you were.”

“Leave me alone.” I turn back to my chemistry homework. But no matter how hard I try to focus my eyes, I can’t make out the oxidation number I am staring so hard at. As I squint, a drop of warm liquid slides out of the safety of my bottom eyelid, leaking onto the piece of paper. The crystal of fluid makes contact with a portion of the instructions on the top of the page. The water pools into the ink, clinging to the fibers. I think about the polarity of water, and for a moment, I hate knowing the chemistry behind my tears. I imagine what might have happened if I had not known the instructions yet or started the worksheet. Could I have gone to Mr. Nick and told him “my eyes consumed my homework”? I wonder what he would have said.

I can’t concentrate anymore. I’m beginning to confuse single and double replacement reactions again. My mother has gone on to look at the album for my seventh birthday. She appears to have her favorites. I rest my chin in the curve of my elbow and think about how much I loathe my mother’s use of the past tense. I don’t have the stomach for nostalgia, for the “weres” and “would have beens” of this world. I can’t reminisce about my childhood without feeling my intestines clench and gurgle inside me like a ticklish fetus. At the moment, I don’t feel like being pregnant with sentimentality.

My mother is stacking up the albums as she finishes with them. She’s moving more quickly now, her fingers accustomed to the routine of pinch, flip, turn, slam, stack. She’s on my tenth birthday now. That was the year I had a tea party at the Plaza Hotel. We binged on petit fours and saccharine pink tea that smelled like my body the time I poured my mother’s rose-scented perfume all over my arms like body oil. For the party, I wore a lovely blue-and-white sailor dress with what I used to call a “poofy” skirt. I wonder what happened to that dress. I notice that there is only one pile of books now, stacked high, and that it is slanting over precariously like the Leaning Tower of Pisa to the left of my mother’s elbow. She is finished. Her eyes lost in the leather, my mother traces the covers, her fingers circling over the hills and valleys of what may once have been animal skin, but now shields my childhood. For a moment, I wonder why my mother isn’t looking at the photographs from my more recent birthdays. I feel the space in my mouth begin to increase in size behind my closed lips, pressed tightly together in the shape of the “m” sound. But just as I am about to interrupt her meditative silence, I slam my jaw closed. I already know why. After my tenth birthday, I began to grow touchy around photographs. I became increasingly conscious of the way my cheeks swelled in pictures that would last forever, the way the dark circles under my eyes sunk into my pale skin like black holes. I stopped letting my mother capture the progression of my smile, either with palms shielding my face from the grenade of the flash, or simply letting my eyes frost over with a hard, angry expression. Sometimes, my mother still managed to capture some images when I wasn’t paying attention, but only with her grainy phone camera. An actual camera would have been much too obvious. After the party, I would demand that she hand over her phone so that I could systematically check the Photos app. I knew where to look—she had grown too intelligent and too practiced to simply leave the photographs in the normal Photos section: she had begun deleting them. These images would remain “hidden” in the Deleted Photos section until my swiping fingers, bent on annihilation, would encounter the bolded red letters warning me that if I chose to delete the already deleted images, I would never again be able to retrieve them. Yes, I told the device. I understand. I would breathe a sigh of relief as I expunged the few moments that my mother had been able to secretly capture—blurry images of my face, neck bent back, as I sipped on a glass of water, or as I turned my back to continue a conversation. None of these snapshots were worthy of preservation. On my most recent birthday, as I handed back my mother’s newly-cleansed phone, smiling strangely with a mix of relief and irritation, she refused to look at me. Her waiting fingers grasped the sides of the slippery case and slid the device into her purse without a pause. She zipped the bag closed and trudged forward into the wet April afternoon. We walked for a few minutes in silence, our steps in sync. As I rubbed my bare arms, the chilliness seeping into my bones, I clenched my jaw. I was peeved at her reaction, but not at all at the fact that she had taken those photographs, despite my many warnings. I had almost learned to enjoy the tradition—to let my mother engage in her foolery, and then punish her for it. But at the same time, I felt almost felt guilty. What other fourteen-year-old would force their parent to hand over their phone so that the child could survey and delete information off of the device? I began to wring my hands, taking a deep breath as I prepared the introduction to my apology—

“You will regret this.” Her crude comment cut sharply through my beautiful, flowery train of thought.

“What do you mean?” I had stopped walking, taken aback by her brusquerie. I folded my arms against my chest, ready to defend myself against any bullet she shot against me.

“One day, you are going to wonder where all these memories are. Don’t come blaming me then. All I’ve ever tried to do is to help you preserve them, to lock them into books that one day you might have flipped through, letting your childhood flow back in.” Her voice was beginning to tremble. “I was a child once, too. I only wish that my mother had taken this effort to hold down those few moments of happiness, before they flew away, and pinned them down to paper. You don’t know how it feels to reminisce and then wonder if your mind is playing tricks on you. You don’t know how it feels to live each day the way the breeze zips through your hair—with you one moment, gone the next. All I’ve been doing is trying to help you save yourself.” Her voice was thick and wet, but also hard, like frozen ice. It seemed that we both already knew this secret—anger is the best kind of tissue. She didn’t wait for me as she continued to march up the Avenue, the brown paper bag holding the leftover cake slamming against her thigh. I let her keep walking, imagining the lilac frosting clinging to the sides of the plastic. Standing off to the corner of the sidewalk, I folded my arms against my chest and hid my chin in the concave formed by my elbows. As my throat began to close, I let myself travel back to my first birthday. I was an infant again, blissfully ignorant of flashing cameras, of the rolls of fat cascading down my pudgy legs. I wondered, momentarily, how I had such clear memories of my toddler self, playing out like a film in my mind. Tucked behind my irises was a leather-bound album, with a series of photographs so similar but for slight differences—a movement, a change in background. My mind had learned to splice the images together, creating its own album out of the memories someone else had found worthy enough to capture.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)