Penguin, 2016

REVIEWED BY JUSTIN HOLLIDAY

–

Kim Addonizio, known for her poetry, fiction, and writing guides, has published her first personal essay collection after two decades after writing. As she often does in her other work, she covers topics such as family, writing, drinking, and sex, but what makes this book so different is that it is truly “confessional” writing in the strongest sense of the word. While all of her writing is unvarnished, Bukowski in a Sundress is the barest truth of the persona Addonizio wants everyone to see.

Some of the essays are written in second person. Rather than feeling ersatz by ostensibly addressing the reader, these particular essays allow Addonizio to express insecurities and frustrations in a way that discusses personal experiences and shows the ways they may relate to others. In her essay “How to Succeed in Po Biz,” she provides a step-by-step guide of sorts for poets:

Feel anxious about the upcoming trip because you hate to travel. Feel anxious because you are basically a private person and can’t live up to the persona that is floating out there in the world acting tougher and braver than you. You are a writer, after all.

This rhetorical strategy is a way to explore the anxieties that many other writers feel. Other essays in the collection similarly meditate on the difficulty of writing itself, from procrastination to writing that appears “DOA” on the page. These essays reveal the possibilities, or perhaps the pitfalls, that even successful writers contend with.

Addonizio’s caustic sense of humor shines in the memoir as well as it does in her other work. From failed relationships to odd encounters in the Midwest, she considers nearly everything worthy of witty, often critical response. Even titles like “Necrophilia” and “Children of the Corn” are used to redefine readers’ connotations of such terms. For example, “Necrophilia” refers to loving the emotionally dead, those who appear alive but cannot reciprocate love. Further, she plays with clichés with other titles such as “Pants on Fire, ” an essay that acts as the ultimate confessional for any poet. Here, Addonizio reveals the “lies” in her poems, which are considered lies only because of the contentious space of poetry within the often-false literary binary between fiction and nonfiction. Amidst her “confessions,” she intersperses other truths she has learned as a writer: “I swear on a stack of Bibles that some men really will want ‘to fuck your poems.”’ Such claims not only express the humor and chagrin of Addonizio’s experiences, but also reflect the mentalities of readers.

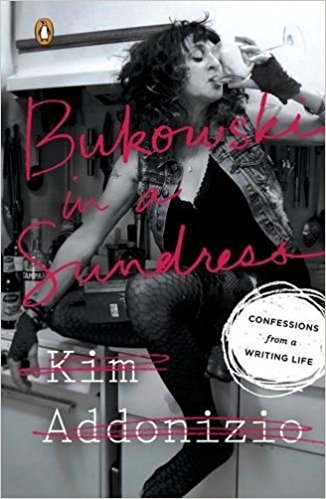

The titular essay actually comes from criticism by a member of the National Book Critics Circle Award committee. When Addonizio was under consideration for the award, one critic dismissed her as “Charles Bukowski in a Sundress,” suggesting her writing was derivative, uncouth, and anti-literary. Regardless of Bukowski’s success, his work is often viewed as flouting “literary” standards, whatever the vaguely and sometimes arbitrarily defined standards may be. While the insult does anger Addonizio, she responds with analogies of her own: “Frankly, I’d have preferred a different, though equally nuanced, characterization of my work—say, ‘Gerard Manley Hopkins in a bomber jacket,’ ‘Walt Whitman in a sparkly tutu,’ or possibly ‘Emily Dickinson with a strap-on.”’ As a poet and a woman, she strives to fight for self-definition, wanting her self-generated comparisons to reflect the creative and occasionally strange but always evocative elements she blends in her work.

Other essays tackle difficult topics that are harder to laugh at; however, Addonizio adeptly reports the seriousness while also trying to acknowledge the humor we can find in our own pain. Essays about her dying mother show tenderness toward her family, reflecting the balance of the woman who has also written about necrophilia, homemade pornography, and the importance of alcohol consumption elsewhere in the memoir. “Flu Shot” provides a look at what it is like for her to be the outsider daughter who rarely sees her mother because they live so far apart. When she writes about the ordeal of trying to get her mother to the pharmacy so that she can be inoculated, Addonizio reveals a struggle that so many families must deal with as parents age. And in this meditation on aging, Addonizio also confronts the emotionally distant relationship she and her mother, renowned tennis player Pauline Betz, have had in the past, finally making some sort of peace with it.

Whether writing about failed romantic relationships or familial conflicts, Addonizio evokes a clear idea of what her life has been like as a writer, a mother, a lover, and a daughter. Although she has reclaimed “Bukowski in a Sundress” as a wry moniker, she is more than that. Kim Addonizio is her own woman, and her writing has revealed that she stands nonpareil, though I would not blame her if she became “Emily Dickinson with a strap-on.”

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)