(Apocalypse Party, 2020)

INTERVIEW BY KELBY LOSACK

—

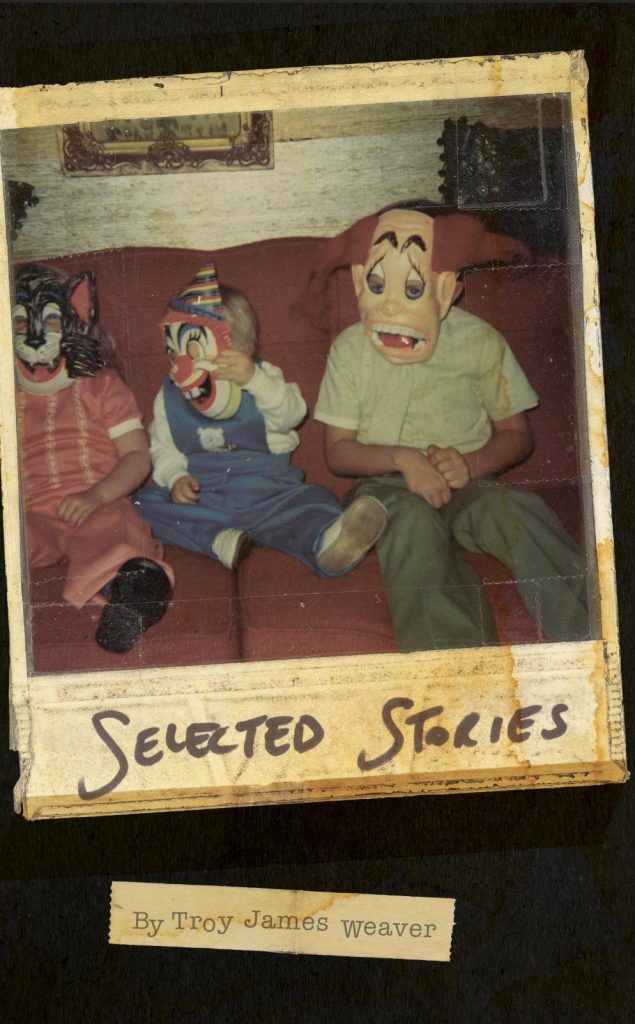

Troy James Weaver is the author of Witchita Stories, Visions, Temporal, and Marigold. He lives in Wichita, Kansas with his wife and dogs. I’ve been hooked on the kid’s writing since seeing his first reading ever in Norman, Oklahoma, where his words and his voice had a smoky bar full of tweakers using their handlebar mustaches to wipe tears from their faces. Weaver’s writing is refreshingly human, finding the beautiful within the ugly and vice versa. His characters are reflections. Though he writes with the experience and insight of a 700-year-old Buddhist monk, I refer to him as “the kid” because—in spite of the loss and heartache spilling from his pen—Weaver writes with a level of empathy only an unjaded child could muster. And that blend of honesty with compassion is hard to find in an increasingly nihilistic, cynical landscape. I reached out one night to discuss with the kid his most recent book, Selected Stories, and after our conversation, I ascended to the highest plane of enlightenment.

Blood doesn’t come out of a puncture much more than a dot. You could run a sharpened dowel through somebody and yank it out and you’d barely see a drop or two. I don’t even know why they bother with the cotton swab after a shot. Just roll your sleeve down and move on. That’s how my brother does it. Sometimes there might be a smear of bleed-through, but it’s rare that you’ll see it. Dark-colored shirts, an expert. He doesn’t bother rolling them down for me, though. He knows I know what he does.

~Troy James Weaver, Selected Stories, 2020 [30]

KELBY LOSACK: The common thread through this collection seems to be this clinging to memories of a lost life, a lamenting of literal death, or what could have been, or of a lifestyle being reshaped around sudden changes. How often was death on your mind while penning these stories?

TROY JAMES WEAVER: All the time. I lost my dad and my father-in-law a year apart from each other. Most of these stories were written during that time, with a couple of exceptions. In choosing the stories, too, I wanted the tone to be consistent.

Experiencing death changes you.

I think my characters are working through the same state of confusion I was working through at the time, though I didn’t realize it then.

KL: There is a strange relationship that’s hard to navigate after a close one passes, right? The way you wrote about characters mourning in “Construction” and in “Instructions for Mourning,” for example—like, sometimes you find yourself mourning in very bizarre ways. Or you try to find ways to communicate with the spirit or memory of that person, in a totem such as an unearthed alien plush toy or one of those lifelike sex dolls. In a way, those are no different than an RIP tattoo, right? What are your thoughts on how we commemorate and communicate with our loved ones post-mortem?

TJW: Yes, it’s very strange. I don’t know that grief goes away and that’s why it’s confusing. Objects become sacred to you because the person who owned the object was sacred to you. I think I communicate through art. Sometimes it feels like an exorcism. In a way, it immortalizes not only them, but us, writer and subject, together.

I have a hard time articulating what I mean, because these immense losses still affect me every day. I’m still trying to figure it all out.

KL: I feel you on that, big time, and I think art is a great way to articulate what can’t easily be expressed. The tone of nearly every part of Selected Stories carries that sense of trying to maintain remnants of the past in a rapidly shifting present.

I remember you mentioning somewhere that this would be your last book for a while. Is this still the case and what made you decide that?

TJW: I’m just tired of publishing shit. I’m going to be writing, for sure. I’m just not going to send it anywhere. Just tired of giving a fuck. I don’t like all the shit you have to do. Like all the posting and the trying to sell yourself shit you have to do.

KL: Yeah, fuck being a brand, fuck selling shit. It’s almost like people turn their noses up, too, when you talk about just caring about the art and they’re like, “yeah, but I gotta put food on the table and blah blah blah,” like okay cool, get a job maybe?

I just dig art that comes from a genuine place that isn’t trying to pander to anything. Art that communicates something beyond “I really wanted a book deal so here’s this algorithmic bullshit.”

I’m of the mind artists should probably never live off of their art. There’s something lost in the voice of someone who’s not putting in some kind of daily grind separate from their art. And maybe that separation of monetary pursuit and creative expression is the key to making honest art? Just feels like a lot of shit is materialistic, lacking soul. How do you think having a regular job affects your voice as a writer?

TJW: Exactly. I just want to feel the pureness of it again. And I do. I think I got lost in the idea that anybody gave a shit. And that’s fine. But I realized I don’t care if anybody else gives a shit. I give a shit. Having a regular job makes the stories happen. Living a regular life makes the stories happen. I’ve never understood these Ivy League, Big Five writers, trying to write about shit they clearly don’t understand. And also, I find their books to be suspect in almost every way and just straight up fucking dull half the time. There are a few exceptions, but most of it is dishonest bullshit. If I see Rhodes Scholar on the jacket copy, I’m passing. That’s all I’m saying.

KL: I fuck with everything you said 100%. What is the remedy to the situation, do you think? Self-publishing, zines, keeping it all to yourself? Something else?

TJW: I don’t know. I mean, I’ll publish again, just not soon. And as for the Ivy-leaguers, they’ll always be there. I think small presses and indie lit and whatnot are fighting the good fight, I just think we should be slinging more molotovs at the establishment. Make them notice. Get in some shit. Sling mud. Talk shit. Burn it down. Don’t be nice just because you think it will help your “career.” You won’t have a career, or it’ll be a mediocre one, if you don’t say what the fuck is on your mind and mean it.

KL: You’re speaking my language, man. I love the attitude. You’ve had a good streak of small press relationships, speaking of… Disorder, Broken River, King Shot, Future Tense… what made you link up with Apocalypse Party for this collection, and whose awesome decision was it to start a love story on page 69?

TJW: Apocalypse Party is just a cool new press. I think [Benjamin DeVos] is a great writer and I love working with people who are truly enthusiastic about what you do. He’s like that. So that’s how that worked out. I half-jokingly tweeted about putting out a collection and he and a handful of other presses hit me up and I already liked Ben and knew what he was about, so I immediately sent him what I had.

As for that story on that page, that must’ve been the genius that is Ben. Or pure coincidence. I’m not telling.

KL: Hell yeah, Ben is good people. Dude’s got good taste in music, too. What have you been listening to lately? I remember thinking of your last novel, Temporal, as like a shoegaze album in literary form. Selected Stories feels like the blues. Like raw, deep south, hole-in-your-gut blues.

TJW: Sparklehorse’s first three records, mostly the first one. That song “Spirit Ditch” is my jam. (Sandy) Alex G. Lewis’ L’Amour. Polvo. Slint. JPEGMAFIA. Nick Cave. Rapeman. Elliott Smith. 100 Gecs. Robert Johnson. Blind Willie McTell. Skip James. Boredoms. Hasil Adkins.

KL: So I wasn’t too far off, got some Blind Willie in there. JPEGMAFIA is my favorite artist of the moment. And I’ve been going back and listening to Two Nuns and a Pack Mule since you turned me on to Rapeman a while back. I think noise music is the perfect soundtrack to our current era.

TJW: For sure. The insanity is a mirror.

—

KELBY LOSACK is the author of The Way We Came In and Heathenish, both published by Broken River Books. He lives with his wife in Gulf Coast Texas, where he builds custom furniture and hangs out with rappers.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)