Editorial Assistant Erinn Batykefer sat down with [PANK] Author Maya Sonenberg to talk about her book AFTER THE DEATH OF SHOSTAKOVICH PÈRE and her role as the [PANK] BOOKS NONFICTION CONTEST JUDGE!

Not all ghosts exact revenge or induce terror. Some emerge from a miasma of grief; sad themselves, they spread sorrow. Or perhaps those left behind—daughters and sons—create the ghost of a father, trying to find what’s surely been lost. Following the four-movement structure of Shostakovich’s Suite for Two Pianos and using a mosaic of story, memoir, photographs, literary analysis, and her own father’s journals, Maya Sonenberg’s After the Death of Shostakovich Père is an extended lyric meditation on the death of fathers, both biological and artistic, and the ways in which haunting can produce art. BUY MAYA’S BOOK HERE

Erinn Batykefer: The fiction and non-fiction you’ve published often have multi-media or hybrid elements: prose and drawings, flash mini-essays. Your nonfiction chapbook, After the Death of Shostakovich Père, came out from PANK Books last year and has a similar shape shifting quality, oscillating between literary analysis, storytelling, and a scrapbook of personal photos and journal entries. Do you draw lines between genres?

Maya Sonenberg: I just had a very interesting discussion with my graduate students about whether we thought of the hybrid literary object in botanical terms or mythological terms. For the former, think of the pluot, a cross between a plum and an apricot that has become entirely its own fruit. For the latter, think of the chimera, a fire-breathing female monster with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail. The former is like a mosaic seen from the distance, while the latter is like a mosaic seen up close so that the separate tesserae are distinct. For the former, you might think of the prose poem. In the works of mine you mention, I see myself working in the latter form—the different genres are placed next to each other but remain distinct.

This is all a round-about way to answer your question: I do see distinctions between genres, and even when I combine them in a single section (the literary analysis in After the Death of Shostakovich Père also includes material about my personal experiences of reading the Borges stories), I’m keen to be clear about what refers to me, what is speculation, what is factual. Many thanks to my students Sarah Bitter, Boston Chandler, and Devon Houtz for the discussion, and to Rose Metal Press for their anthology Family Resemblance, which introduced us to thinking about the hybrid as a mythological creature.

EB: What excites you about judging the Big Book Nonfiction contest for [PANK]?

MS: These days both fiction and nonfiction are capacious, and I love that. Nonfiction in particular is a great big tent, including speculative essays and rather straight-forward memoir, essays about something big and important—or tiny and important—out in the world conveyed through a personal lens, essays that borrow forms from other sorts of writing and essays that proceed through collage or logic. I’m just excited to see the different sorts of nonfiction I’ll get to read.

EB: After the Death is listed as memoir / personal essay, but in a lot of ways it does its own thing to create an elegy for your father that mirrors the musical elegy Shostakovich wrote in the wake of his own father’s death. Was (mostly) nonfiction the obvious choice for this project?

MS: When I started this particular project, I actually planned to simply write a short story based on Shostakovich’s experience of losing his father during the Russian Revolution and going on to write the duet for two pianos. Pretty quickly, I realized his many biographers had already covered this, and I began to allow all sorts of material about dead fathers to accrete to the project. The ghost story that makes up the third section came from a novel I had never completed. I decided to write about the Borges stories because I was (and still am) in the midst of several other projects in which I pair a real ancestor with someone I think of as an artistic forbearer. I knew this project would be about my father, but I didn’t turn to including the material from his notebook until after I had figured out the structure of the piece. Each section corresponds to a movement in the piano duet, and within each section, the different literary and photo threads correspond to changes in melody and/or tempo. I suddenly had many different threads I needed to create and the material from his notebook fell pretty neatly into a separate categories

EB: What are you hoping to see in the submissions for this contest? What, in your opinion, should a book of nonfiction do? What are you hoping to feel while reading a winning work?

MS: I honestly cannot make an over-arching claim about what a book of nonfiction should do, but when reading a winning work, I’m hoping to feel hit between the eyes—that I’m reading something really unexpected, forced to see or experience or think about things in a new way. I know—what does that mean? I want to read prose that is aware of its own power and has developed its own style, rather than attempting to be transparent. I want to read memoir in which the writing persona questions and re-questions itself or makes bold claims about itself. I want to read essays about the big bad world that are still somehow personal. I want to read lyric essays that get their components to sing to each other, hitting that sweet spot where the subtle and the obvious cancel each other out. I want to read content or form or style that I can’t even imagine as I answer this question. This is not to say winning works need (or could!) do all of the above. Some might do only one.

EB: The Finale section of After the Death includes a meditation on Borges’ “The Library of Babel” which was a literary touchstone you found ridiculous later on. Is revealing a state of balance like this (or perhaps coming to terms with the necessity of cognitive dissonance) the project of writing?

MS: As perhaps you’ve seen by now, I don’t think there’s only one project for writing to complete or accomplish, so I’m not really sure how to answer this. I like states of balance, cognitive dissonance, and friction in writing, but I also love a good novel that sucks me right in to its world. I love the calm world of a book like Sarah Orne Jewett’s Country of the Pointed Firs! In my current writing projects, I’m trying to explore both-and, rather than either-or, thinking.

PS—I hope my continuing love, tempered now by many re-readings, of “The Library of Babel” still comes through. [It does!]

EB: If you could encourage the writers who will be submitting their work to [PANK] for this contest to read one book before they hit send, what would you choose?

MS: Ah, not before they sit down to write, but before they hit send! Before they sit down to write, they should read whatever book they love most and take inspiration from it. Before they hit send…. I’m not sure. Again, I can’t think of any one book that would give writers a quick window into my predilections.

EB: Anything else you’d like to share with [PANK]? [PANK] would party with you any day.

MS: I would party with [PANK] any day to

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)

18. Bruja by Wendy C. Ortiz. What Ortiz does for the memoir here is comparable to what Flaubert’s Madam Bovary did for modern realist narration or what Capote’s In Cold Blood did for the nonfiction novel. Simply put, Ortiz’s “dreamoir” is a new thing and this book will be the starting point for a movement as well as the go-text for all upcoming memoirs that inhabit the interstitial space between reality, memory, very personal surrealism, and dreams.

18. Bruja by Wendy C. Ortiz. What Ortiz does for the memoir here is comparable to what Flaubert’s Madam Bovary did for modern realist narration or what Capote’s In Cold Blood did for the nonfiction novel. Simply put, Ortiz’s “dreamoir” is a new thing and this book will be the starting point for a movement as well as the go-text for all upcoming memoirs that inhabit the interstitial space between reality, memory, very personal surrealism, and dreams. 17. Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones. Going into a poetry collection without being familiar with the author’s work is always an adventure. With this book, the adventure yielded a treasure trove of southern imagery, a screaming celebration of roots and culture, and an unapologetically raw view of the female African American experience. This is brave, beautiful, necessary poetry that should be taught in schools and that undoubtedly becomes more important with each dumb step the country takes backwards.

17. Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones. Going into a poetry collection without being familiar with the author’s work is always an adventure. With this book, the adventure yielded a treasure trove of southern imagery, a screaming celebration of roots and culture, and an unapologetically raw view of the female African American experience. This is brave, beautiful, necessary poetry that should be taught in schools and that undoubtedly becomes more important with each dumb step the country takes backwards. 16. A Collapse of Horses by Brian Evenson. Evenson is one of the most talented living writers in the world, and this collection is full of stories in which he proves it time and time again. Sad, strange, creepy, touching, surreal, scary; if you can think it or feel it, Evenson does it here. The best short story collection of 2016 and yet another superb entry into the oeuvre of a man who seems to only get impossibly better with each new offering.

16. A Collapse of Horses by Brian Evenson. Evenson is one of the most talented living writers in the world, and this collection is full of stories in which he proves it time and time again. Sad, strange, creepy, touching, surreal, scary; if you can think it or feel it, Evenson does it here. The best short story collection of 2016 and yet another superb entry into the oeuvre of a man who seems to only get impossibly better with each new offering. 15. Black Wings Has My Angel by Elliott Haze. The folks at the New York Review of Books know how to pick their classics, and this one is my favorite so far. A narrative that still resonates in modern noir’s DNA, this is a dark, twisted tale of love, violence, secret agendas, and the way plans have a tendency to crumble.

15. Black Wings Has My Angel by Elliott Haze. The folks at the New York Review of Books know how to pick their classics, and this one is my favorite so far. A narrative that still resonates in modern noir’s DNA, this is a dark, twisted tale of love, violence, secret agendas, and the way plans have a tendency to crumble.

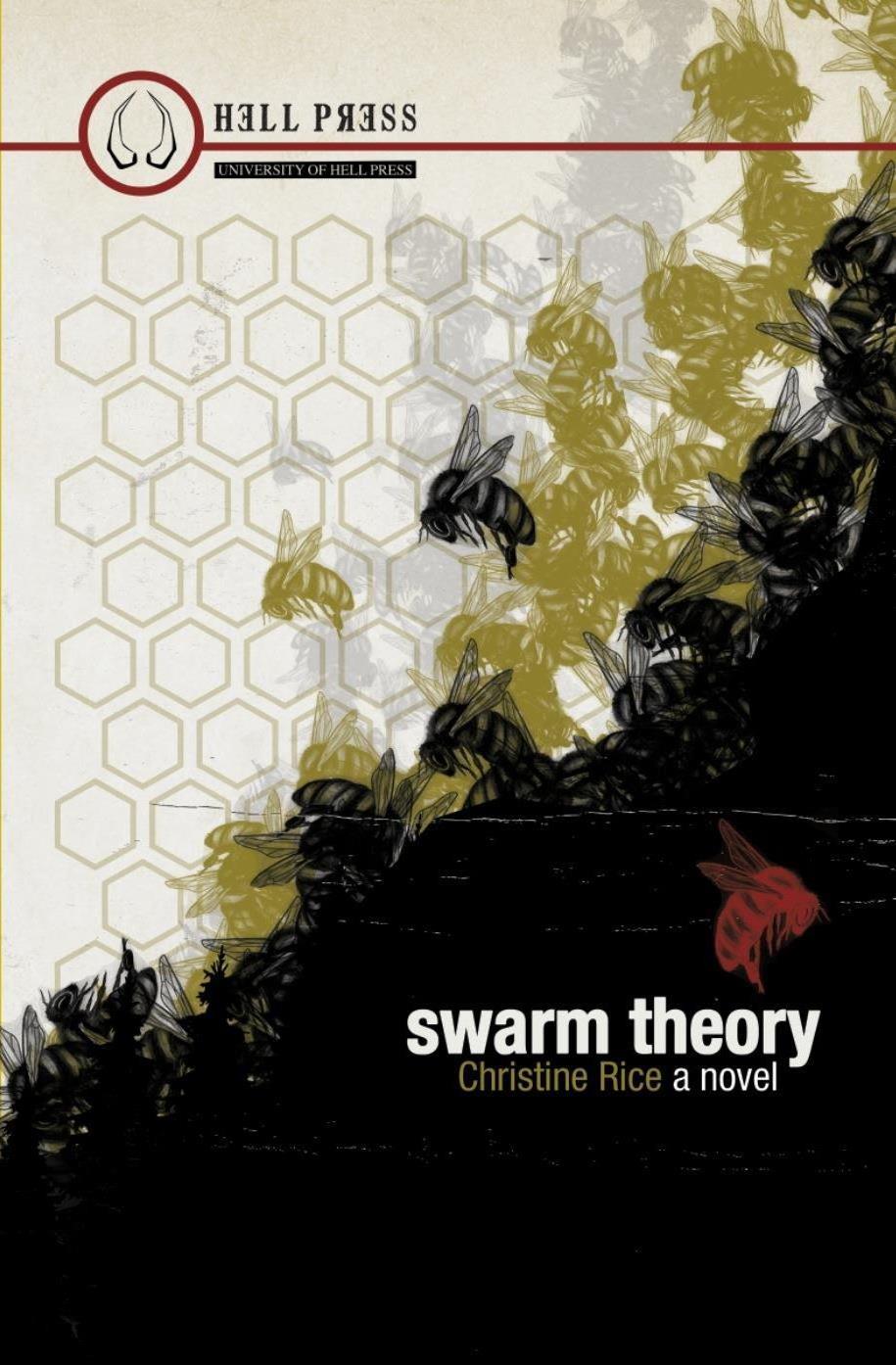

2. Swarm Theory by Christine Rice. I could write ten pages on the way Rice weaved together a narrative about a whole town and all its denizens, but that would probably bore you. Instead, I’ll say this: Swarm Theory is the most impressive book about a town/plethora of characters that I’ve read since devouring Camilo Jose Cela’s The Hive, and remember that Cela got a Nobel in Literature in 1989.

2. Swarm Theory by Christine Rice. I could write ten pages on the way Rice weaved together a narrative about a whole town and all its denizens, but that would probably bore you. Instead, I’ll say this: Swarm Theory is the most impressive book about a town/plethora of characters that I’ve read since devouring Camilo Jose Cela’s The Hive, and remember that Cela got a Nobel in Literature in 1989.