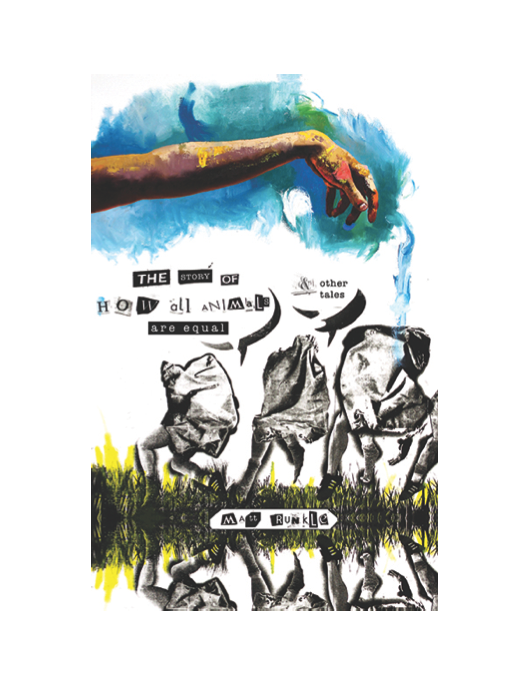

158 pages, $15.95

Review by Anna Mebel

Matt Runkle is both a writer and a visual artist currently studying at University of Iowa’s Center for the Book. He writes short stories and prose poems, makes collages, comics, and art books. Though The Story of How All Animals Are Different & Other Tales is his first book of short stories, Matt Runkle has also published a zine called RUNX TALES. As an artist, he is interested in assemblages, juxtapositions, things that most people would discard. These artistic practices filter into his writing. In The Story of How All Animals Are Different & Other Tales, Runkle mixes fairy tales, love stories, satire, dystopia, prose poems, and careful observations of the ordinary.

The stories are often very short but always efficient, showing us flashes of worlds similar to our own, yet slightly off—an apocalyptic scenario in which people live out of their cars, a supermarket located on the border between two countries, a town in which the punishment is election to public office. He finds “places where comings and goings occur from every side,” where borders dissolve and relationships become unstable, letting worrisome aspects of human nature emerge. Continue reading

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)