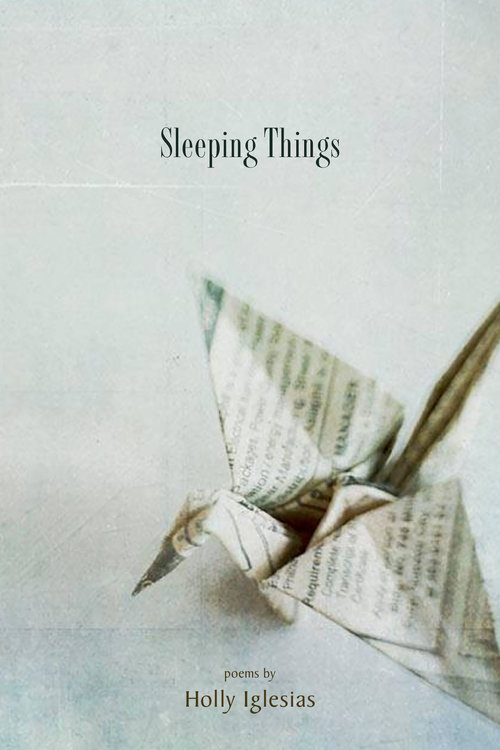

(Press 53, 2018)

REVIEW BY CLARA B. JONES

—

Holly Iglesias is a prose poet, a critic, a translator (Spanish), an educator specializing in documentary and archival poetry, a feminist, a lesbian, a traveler, a recipient of fellowships and awards, as well as, a member of the Cuban diaspora in the United States. As her poems attest, she has a strong sense of memory and place, in addition to an abiding concern for the status and welfare of children and women. Sleeping Things (2018), her third full-length collection, includes poems highlighting her thesis, advanced in her critical essay, Boxing Inside The Box (Quale Press, 2004), that the prose poem, a form of ancient origin, symbolizes the constraints borne by women [all oppressed groups?] boxed into bedrooms, kitchens, churches, bodies—literally, figuratively, and psychologically: “Oh, victim soul, don’t bite back. Instead, sink deeper/and deeper into the bed, into sheets thin as pity, pillows/flattened by the weight of piety.” (p 18, Sleeping Things); “Mother is the superior of our kitchen, her habit an/ apron.” (p 20). I first met Iglesias after a reading in a bar, Crow & Quill, in Asheville, NC (p 69), filled with a group of her dedicated admirers, with whom I soon identified.

Sleeping Things, a volume in three parts, is titled and introduced by Federico García Lorca’s words, a poet referenced elsewhere in Iglesias’ writings. Clearly, she has been influenced by Lorca’s Surrealism (“automatism,” unconscious processes: “ A Child’s Book of Knowledge…”, pp 14-15, 21; “Remote Control”, p. 26) and his “deep song” form (“The body sojourns but briefly in the material world…”, p 4; “The grandeur of possibilities soothed/my shame. Should I stand shoeless for days in Alpine/snow…?”, p 24). Part I of Iglesias’ new, handsomely crafted and illustrated book, presents poems with multiple layers of significance, demonstrating the ways in which her childhood experiences, musings, and recollections relate to historical and current events documenting the author’s routes to an awakening of socio-political consciousness: “We were a system, a sociology, a discipline of black/and white, its strictures softened by Gregorian chant/and myrrh, by the nuns pacing left and right [sic] as they/tapped the maps with a flourish—Holy Roman Empire,/Barbarian Invasions, Counter-Reformation.” (p 7). The poet’s vivid historical, psychological, spiritual, and metaphorical tapestries reveal her ongoing interest in causal, situational, interconnected, as well as, multi-level memory, time, place, relationships, and identity inherent to personal, local, regional, national, and international domains (see, for example, “Hit Parade”, p 27).

Part II of Sleeping Things reprints poems from her chapbook, Fruta Bomba [tr. Papaya or female genitalia; Making Her Mark Press, 2015]. Although Iglesias may be viewed as a “political” writer, these poems, like others throughout the book, demonstrate her lyrical, intimate style transcending sociology, literalness, and didacticism: “No words precede the reef, none follow. Only sea fans,/brain coral, clouds above the surface. Glint of sun, of/barracuda and baitfish in flight, the Gulf Stream/sweeping by, squeezing between Florida and Cuba….” (p 31). Iglesias often refers to events in Cuba, Miami, and St. Louis, especially, the physical and emotional distances between these places, as well as, other locations. Her poems about tropical areas authentically reflect their sensuousness—color- passion-soul (components of Lorca’s duende), exoticism, mystery, and, sometimes, the potential for violence (“The boy, crying, clutches the neck of his rescuer as a/federal agent in riot gear yanks him away.” (p 44). Though Iglesias has clearly renounced the [optimistic] Modernism characteristic of José Martí and Lorca, the poems in Sleeping Things are not depressing or nihilistic. They reflect, rather, an awareness of the complexities and contradictions of the post-World War II political landscape, refusing to advance unifying solutions, as the Modernists did (e.g., Science, Psychoanalysis, Communism). Nonetheless, each section of this book demonstrates that Iglesias’ compositions are part of the experimental tradition, particularly, in their forms (e.g., pp 14-15, 17, 21, 42, 45, 56).

Part III is the strongest section of the book, in part because it highlights Iglesias’ strengths with words—double-meanings, word-parings, complete sentences, as well as, whole poems. Many titles, for example, are playful conceits (e.g., “Lobal Warfare,” “Uncivil War…,” “The Game of Crones”). Also, my favorite line in the volume occurs in Part III (p 60): “It was still life [sic] after she’d gone—hair in the brush,/scented talc, the impress [sic] of her younger self in the/cushions of the couch.” Further, the most lyrical, metaphorical, and imagistic poems can be found in this part: “The first time I saw the Mississippi from the air,/I knew my place, and I knew that home was a sinuous/ribbon lacing east to west, past to future, bondage to/possibility, appearing and disappearing like a snake in/new-mown hay as the sun flashed on its surface.” (p 51). In my experience, music and meter, Formalist criteria, do not often characterize contemporary prose poems; yet, Iglesias achieves these heights over and over again. Sleeping Things contains some of the most beautiful prose poems I have ever read.

Reflecting upon Iglesias’ body of work leads me to recall Louise Bogan’s line: “Women have no wilderness in them; they are provident, instead.” I wonder whether Bogan and Iglesias, are underestimating women and other oppressed or suppressed groups—their capacities for change, transformation, as well as, agency? Having said that, I think the reader will agree that many of the compositions in Sleeping Things are noteworthy, deserving a wide audience. Among feminist poets writing today, Holly Iglesias is one of my favorites, and, if her canon were larger, she would certainly deserve critical attention relative to Adrienne Rich, Alice Walker, and Elizabeth Bishop. Iglesias’ compositions are mature examples of the prose poem sub-genre, and, at their best, the writings stun in their ability to combine “color” with theme (additional Formalist criteria). I have learned a lot about style and metaphor from studying Iglesias’ project, and I am always left hungry for more after reading her books. Absorbing Sleeping Things was a pleasure, and I highly recommend this significant collection to anyone interested in compelling innovative literature.

—

Clara B. Jones is a Knowledge Worker practicing in Silver Spring, MD, USA. Among other works, she is author of the poetry collection, /feminine nature/, published by GaussPDF in 2017.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)