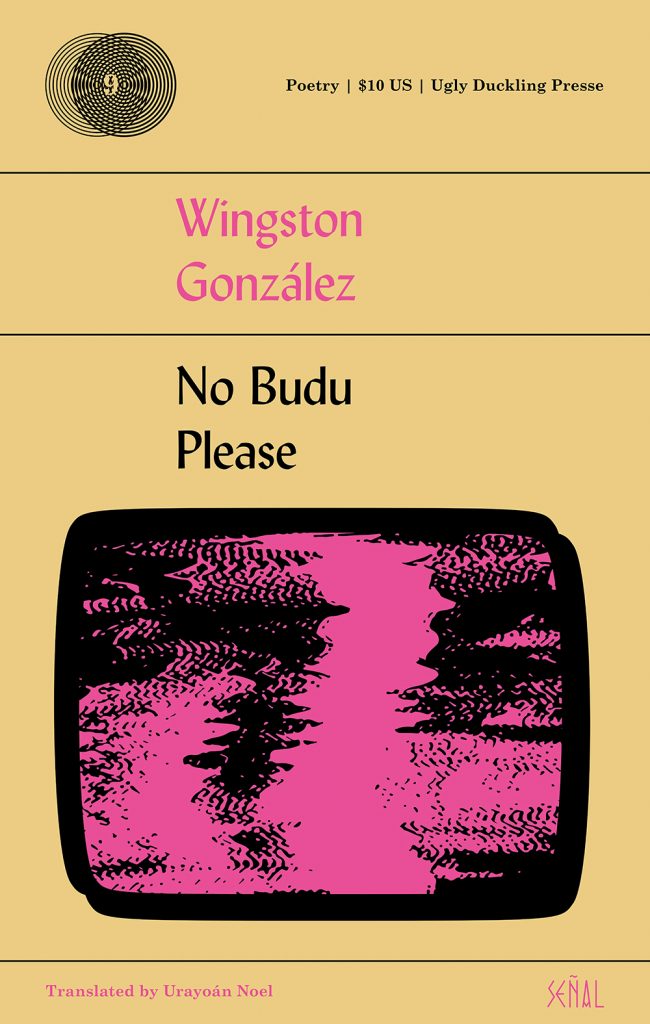

(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2018)

REVIEW BY TRISH HARTLAND

—

On a street corner leeched of humus, of warmth, of sun No Budu Please has me scratching the air with YESSÌYESSÌ. Ugly Duckling Presse’s edition grants the reader Wingston González’s Spanish and Urayoán Noel’s English translation of it, set inside the book so that both of their ends touch in the middle, 69-style. Hold the book in closed position, flip it vertically once in your hands, and you arrive at the beginning of the other version. Which is the ‘other’? The edition grants us permission to answer: there are no others. Or maybe it’s more complicated. It’s as if the physical book materially incarnates what is at the crux of No Budu Please: “dis language represents da other. translashun jentlemen.” Language becomes taken in hand then eclipsed by poetry, made to twist and mutate in service of the poet-tongue. The reader-writer-translator triumvirate here jointedly emanates out from a shared axis of post-disillusion, something like the spectral “butterfly robotic misfortune” being teemed from this tongue’s own liminal spaces, rendered by technology and colonialism and ingurgitated-regurgitated interior-cum-exterior conflict: “da false memories of history […] Babagüicho. Belise City. don’t touch your dead great-grandparents food. HBO an 50 Cent.” There is no surveillance here because all agents have already-always been complicit in the making of this world, and in the naming of this speaking-self “as a boyasabambamm.” Versions do not oppose each other, Spanish odd pages aren’t pitted against English evens as in more conventional “facing-page” books of poetry in translation, in part because neither ‘version’ sits tamed in their originary language. This layout is political.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence, then, that we arrive at the first poem/a: “myth/mito de/of otro/another self/mismo.” Here, epitaph-ing off of Walt Whitman, the I/he/we/they of many sentientized organically-cyborg artifacts twist and writhe until all [non-/] present presentnesses fuse into one, amalgamate their movements in a more-than-choreographed gestus à la Brecht and formulated for the page. Movement speaks. Movement transforms itself. Movement transforms meaning through its folds/unfolds. Return to the site of your footmark in a puddle. Swirl what you’ve already displaced until what was disturbed, shook-up into watery suspension now makes a new song, and you might see something akin to what’s shaken-up into newness here.

All of our we’s move into/toward an instigation. A probing. A re-twist: “what will become of the gothic boy/ for whom culture/ is an accumulation of ideas/ provided to be erased/ by entropy. nothing/ written sculpture, everything/ at the mercy of an unknown/ energy that spreads, that divides/ the inanities of the people/ who tomorrow, at this time/ will have forgotten their own/ frozen blood”. The reader is no voyeur. The reader is too far inside to be passive-witness. We are in the action of this language. González & Urayoán draw us magnetically into the site of a brissage, a crack in our-now-shared tongue’s foundation, from which the Fecund propulses, from which the Fecund finds and inhabits us, our language/z: “da tung approaches, da tung cits down/ an orders a drink/ da tung breiks da rules of speling/ yet he/ now only knows how to see da lites/ an period.” Come here for breaking. Stay for what grows from it.

—

Trish Hartland is an MFA candidate at Notre Dame and enjoys translating works that insinuate themselves into bendable tongue-borders. Recent samplings of poetry and translation can be found around the internet, and her co-translation of Raphaël Confiant’s Madam St. Clair, Queen of Harlem is forthcoming with Dialogos Books.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)