(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2019)

—

REVIEW BY CLARA B. JONES

SOMETHING

night as you go

lend me your hand

work of a teeming angel

days commit suicide

why do they?

night as you go

good night

Alejandra Pizarnik

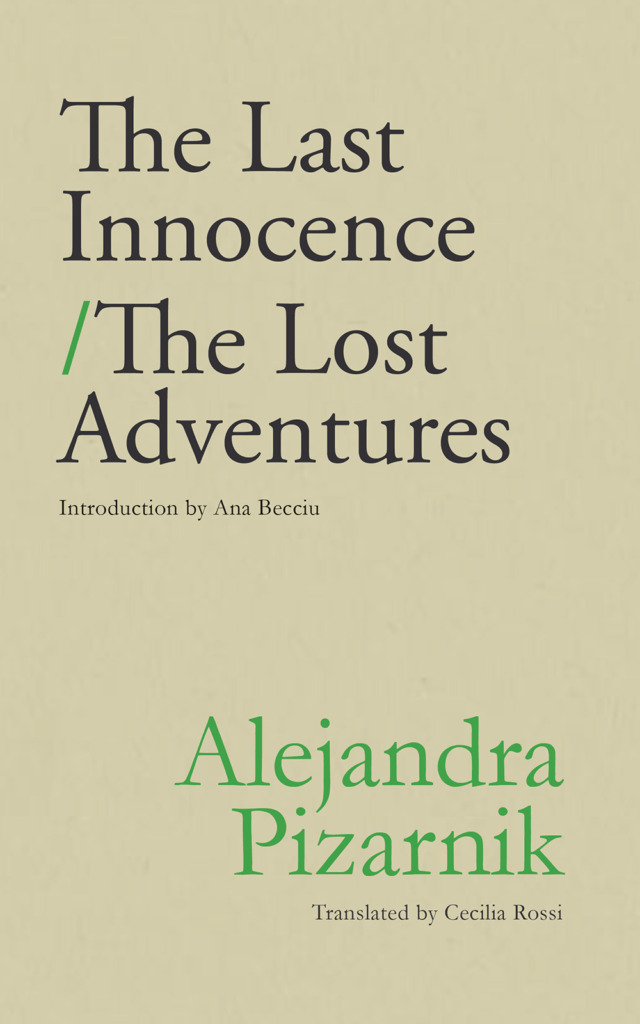

Ugly Duckling Press sponsors a Lost Literature Series that “publishes neglected, never-before-translated, or scarcely available works of poetry and prose.” Painter and writer, Alejandra Pizarnik (1936 -1972), is among the avant-garde writers highlighted—a daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants to Argentina who died from an overdose of Seconal while on furlough from a mental institution. Most of the online and textual sources that I consulted label her death, “suicide.” It is well-documented that Pizarnik endured challenges growing up, particularly problems affecting her physical appearance (acne, weight gain) and social presence (stuttering). However, she coped sufficiently during some periods as a young adult, living and studying in Paris for four years and traveling widely on Guggenheim and Fulbright awards. I first became familiar with Pizarnic when conducting research on Marosa di Giorgio, another South American poet resurrected in Ugly Duckling Press’ recovery project. Marjorie Agosín’s edited volume* provided useful “portraits of Latin American women writers,” documenting that, of the sixteen included in the book, six died tragically—among these, four poets who died by suicide.

The Last Innocence/The Lost Adventure comprises two poetry collections, published 1956 and 1958, respectively, of mostly short pieces revealing Pizarnik’s self-absorption and dark mien, presented in styles that are difficult to classify, though she is generally placed among the literary Surrealists (unconscious motivation, dream analysis), with a current of Romanticism (inner world, feelings, emotions). Like her noteworthy visual art, however, Pizarnik’s poetry demonstrates an affinity to Expressionism’s emphasis upon emotion, exaggeration, anti-realism, and psychological reality. It was also an important movement in the fine arts in Argentina during the 1960s, according to Edward Lucie-Smith (Thames & Hudson, 2004). It is not clear to me why Pizarnik switched from literary studies to painting and then to writing; however, an online source suggested that she considered one of her teachers—“pre-Surrealist” Giorgio de Chirico— to be a poor artist, and therefore possibly a source of disillusionment for the young student.

Argentina has the highest per capita number of psychoanalysts in the world, and one online report is titled, “Almost everyone in Buenos Aires is in therapy.” In addition, Argentina has high rates of depression and suicide. Pizarnik wrote in this psychosocial milieu, combined with a political context characterized by authoritarianism and military dictatorship. Although Pizarnik was a lesbian (or more probably bisexual) the scholar David William Foster pointed out that, “Her poems reveal only scant same-sex markers,” a characteristic that Foster attributed to the need to remain conventional under repressive regimes. On the other hand, a 2015 article by journalist and editor Emily Cooke demonstrates that, in letters to her analyst, León Ostrov, to whom The Last Innocence is dedicated, Pizarnik spoke openly, even flirtatiously, about her sexual attractions and fantasies (especially in Letter #10 dated 12/27/1960) and that she was consciously aware that she (and, he?) had entered the Freudian stage of “transference,” where unconscious sexual motivations transfer from patient to therapist and vice versa.

Indeed, the letters discussed by Cooke suggest to me that Pizarnik’s correspondence to Ostrov may have been manipulative, though, to what end? The letters leave the impression of a playful girl, and Enrique Vila-Matas, writing in Lit Hub in 2016, states, “The dark force of her Immaturity produces an irresistible attraction,” different from today’s “academic lyric poetry.” Pizarnik had a history of rebelling against the academic establishment, a characteristic that she shared with the Expressionists. But The Last Innocence/The Lost Adventures, collections written before her residence in Paris (1960-1964), has more affinities to Surrealism as compositions representing the poet’s unconscious psychological states of being and deep motivational drives (e.g., epigraph poem).

Indeed, the letters discussed by Cooke suggest to me that Pizarnik’s correspondence to Ostrov may have been manipulative, though, to what end? The letters leave the impression of a playful girl, and Enrique Vila-Matas, writing in Lit Hub in 2016, states, “The dark force of her Immaturity produces an irresistible attraction,” different from today’s “academic lyric poetry.” Pizarnik had a history of rebelling against the academic establishment, a characteristic that she shared with the Expressionists. But The Last Innocence/The Lost Adventures, collections written before her residence in Paris (1960-1964), has more affinities to Surrealism as compositions representing the poet’s unconscious psychological states of being and deep motivational drives (e.g., epigraph poem).

Vila-Matas refers to Pizarnik’s story as “an unstoppable myth,” and much has been written about the themes of childhood, not-belonging, woman-as-hostage, and silence in her oeuvre. In 2006, scholar Susana Chávez-Silverman referred to the poet’s “complex textual self” expressed in “a variety of…voices”—dolls, little girls, “automata,” animals, the wind, etc. Pizarnik’s writing has often been compared to that of Silvina Ocampo, Emily Dickinson, and Sylvia Plath—Ocampo because of the tendency to “decouple emotion and action”: “…a dead bird / is flying toward despair / in the midst of music / when witches and flowers / cut the hand of the mist. / A dead bird called blue.” (49); the other two poets because of an emphasis upon death, dying, and interiority: “…there is something that tears the skin, / a blind fury / running through my veins.” (21).

In a 2019 Bookforum article, Cooke discussed Plath’s letters to her (female) therapist, showing the poet to be supplicatory, demanding, desperate for attention and aid, and, in the words of poet Vijay Seshardri, “psychologically sensitive.” While Pizarnik’s letters to Ostrov are clearly attention-seeking and, possibly, unconscious cris de coeur, she performs her writing with vigor and feigned or exaggerated self-confidence rather than Plath-like neurasthenia. Nonetheless, some psychologists speak of the “Sylvia Plath effect”—the purported association between creativity and mental illness. Indeed, following an American Psychological Association article, Aristotle wrote “that eminent philosophers, politicians, poets, and artists all have tendencies toward ‘melancholia.’” It is a simple point to observe that Pizarnik’s persona is consistent with the Plath effect; however, unless I am mistaken, the validity of the hypothesis is controversial among psychologists and feminists—open to interpretation, gendered, and lacking hard evidence.

In a recent New Yorker interview between editor Kevin Young and Seshadri, Plath was discussed in terms of several traits, some applying readily to Pizarnik. For example, in contrast to the classicism of Elizabeth Bishop, Seshadri pointed out that Plath’s writing is “absolutely individuated—it’s very hard to see Plath as an exemplar of anything but her own situation and condition.” One might consider this characteristic to be an artistic limitation; however, both Plath and Pizarnik have proven to have lasting popularity, particularly among women and the young, raising issues of “gendered and sexualized” self/ other contrasts as well as spectors of “power and powerlessness,” topics discussed in numerous scholarly and critical papers available online. Seshadri goes on to point out that both Bishop and Plath wrote poetry that communicates “wildness” and animality, also features of Pizarnik’s writing as noted above.

To speak of self/other raises questions about “alterity,” a topic fundamental to the Lacanian psychoanalytical traditions in Argentina. For Lacan, the Other is the subject—symbolically and metaphorically, and the role of the Other is to mediate its relation to the unique, “individuated” subject in a dialectical manner. Thus, Pizarnik’s “you” may be understood to be herself: “this dismal obsession with living / this distant madness of living / it’s dragging you down alejandra don’t deny it” (17), suggesting a circular, internal, “individuated” relationship of the poet to the environment that is, presumably, unconscious– “I must go / but on you go, traveller!”(25). Perhaps this characterization of Plath and Pizarnik relies too heavily upon a conceptual framework implying narcissism; however, more than one scholar has interpreted Pizarnik’s self-absorption in this manner (see, for example, Stephen Gregory, 1997, Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, vol. 74). To speak of self/other or subject/object incorporates another of Lacan’s essential ideas—“mirroring.” the process of objectifying the Ego, typifying “an essential libidinal relationship with the body-image”: “alejandra alejandra / beneath I am me / alejandra” (29). Pizarnik entered psychoanalysis at a relatively young age, demonstrating a precocious grasp of its canon in letters to Ostrov; thus, authentic and accurate critical scrutiny of her oeuvre must include evaluations of Lacanian psychoanalysis on her state of mind, behavior, socio-economic-political contexts, values, attitudes, opinions, and writing.

Vijay Seshadri noted that Plath’s poems are “not just held together by form.” Similarly, Pizarnik’s compositions rely not only upon innovative uses of lineation, punctuation, and other grammatical conventions, but also upon complex semantic, imagistic, and musical features transmitting powerful emotional content open to multiple interpretations, including possibilities for identification—no doubt major determinants of Pizarnik’s appeal and endurance, particularly for women and young adults. Cecilia Rossi’s sensitive translations will widen Pizarnik’s readership and contribute to the increasingly common recovery projects of female writers and visual artists forgotten, lost, passed over, overpowered, or dismissed. Too many of these women lived or died tragically; the least we can do is to honor their work.

*Borinsky Alicia. Alejandra Pizarnik: the self and its impossible landscapes. pp 291-302 in Marjorie Agosín, Ed. A dream of light & shadow: portraits of Latin American women writers. (1995) University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

—

Clara B. Jones is a knowledge worker practicing in Silver Spring, MD, USA. Among other works, she is the author of Poems for Rachel Dolezal (Gauss PDF, 2019). Clara also conducts research on experimental literature and art & technology.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)