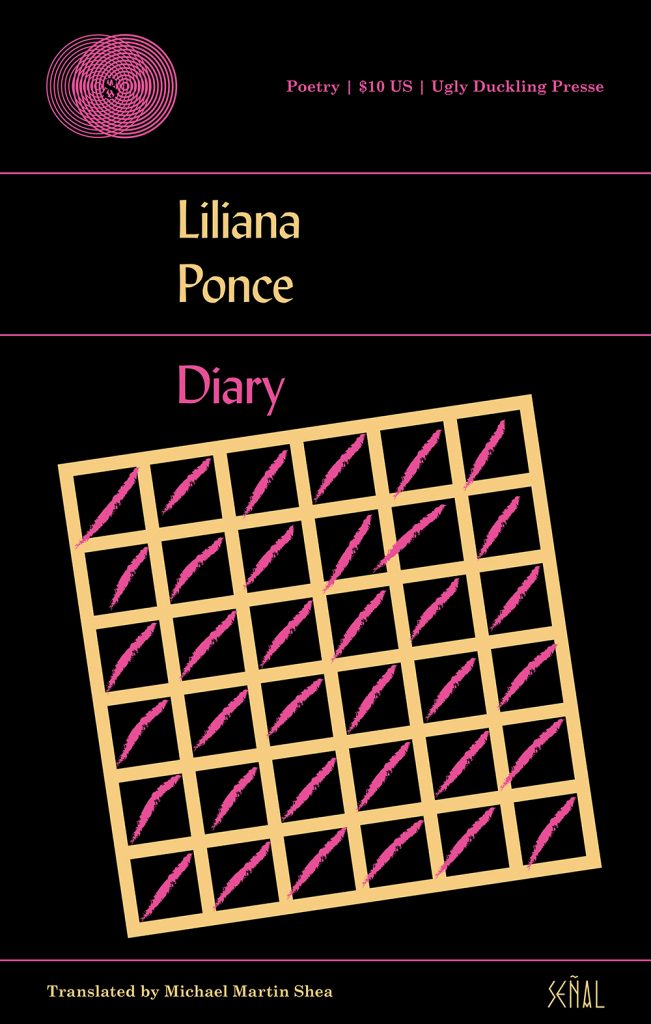

(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2018)

REVIEW BY MAXIME BERCLAZ

—

In the second entry of Diary, on the first page, we are met with the desire to return to the beginning: “I want to start over. It’s an exercise of abstention—to/develop the sensibility of the air.” This desire repeats, is actualized, moves from a wanting to a declaration, then an explication. From “I want to start over,” to “I begin again,” to “What is it that begins again? Writing,” or “What is it that I begin again? Writing,” whichever variation you prefer, the poems circle around a perpetual renewal of their own making, their own writing.

The writing that Ponce begins again and again is that of the construction of “another nature,” an impossible forest in summer, that through her language she makes immobile in its re-creation. The nature described is crystallized by abstraction, an idea that springs not from its own center but rather originates in the trace made of it by the sun and wind. Questions, concepts, and epigrams become halfway concrete while naturalistic descriptions undergo an equally partial sublimation. Rhetoric and image swap clothes, faces.

The oscillation between the two, this modulation of nodularity and hollowness, leaves the writing precarious. It is a writing suspended over the abyss of its birth because of its refusal to turn away from it, always on the point of collapsing back into silence. Yet this instability gives the language a density, a brightness of resonance, made possibly only by this proximity to its source, the site of its un-and-remaking. In the monotonous body of summer, Ponce sculpts a closed circuit where air can chase the beginning like a hound. Against the line of progress she makes a circle where “trees grow on top of silence,” where she can start over, again and again, free from history.

Or she would if not for the titular form. Yoked to the diary, the poems are pressed into the net of calendar time. It may be time at its most bare, twenty numbered entries, nothing to indicate a chronology other than the series itself, but the slip of forward motion is there. In Diary, “The future is like a hole,” one that leads to “the sinking into that diffuse space, that diffuse time, in which we will not be,” and yet the very organization of the book produces that hole in the act of reading. Despite the congealment of language it flows at zero viscosity, into the depths of the future.

Against the line, against the circle, we move into the spiral. Writing becomes coterminous with history. There are repetitions, moments of alignment between coils; crises of production, riots, revolutions, failures, but we can never go back to the beginning. We embrace the collapse that threatens language, we turn to the abyss not as a place of rebirth but a pure uncertainty. Through silence we find utopia, the space and time where we will not be. Only there can we find the pleasure of writing Ponce describes, “its anarchic joy.” Anything less would be suicide.

—

Maxime Berclaz is a first year candidate for an M.F.A. in Poetry at the University of Notre Dame and an Editorial Intern at Action Books. He has been published in Poems for Freedom, an anthology of poems put together in support of the anarchist bookstore Freedom after its firebombing, and The Grape, Oberlin’s alternative newspaper.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)