The Up Drafts is an ongoing series of essays and interviews that examine creativity, productivity, writing process, and getting unstuck.

—

BY NANCY REDDY

Hannah Rule is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at the University of South Carolina, where she teaches graduate and undergraduate courses in first-year writing, writing and embodiment, a survey of composition studies, and the teaching of writing. I first came across her work in 2016, when I attended a panel at an academic conference of writing teachers and researchers, the Conference on College Composition and Communication Annual Convention, where she presented research that attempted to capture the writing process through video recording her own hands on her keyboard as she worked. This video– mundane as that may sound–was fascinating, and the image of writing captured in real-time, with all its pauses and backspaces and bursts of energy, has stuck with me for years. I think of it often as I’m sitting at my own keyboard, particularly when my own hands are still. Since then, she’s published articles that examine how writers interact with their writing environment, as well as how students use freewriting, and her book, Situating Writing Processes was recently published. The open-access version is available through the WAC Clearinghouse, and the print version is forthcoming from the University Press of Colorado.

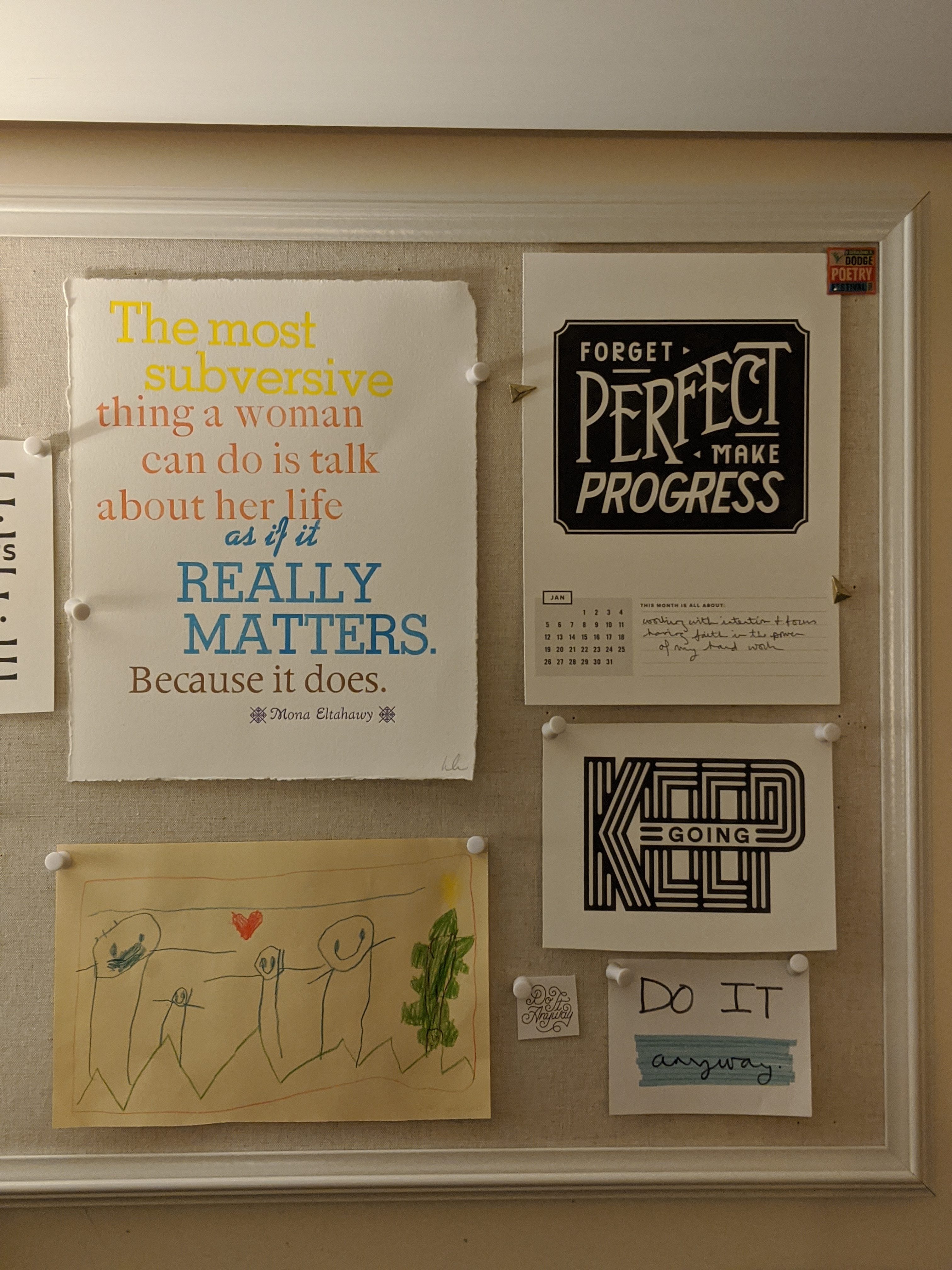

Her new book, Situating Writing Processes, calls up an idea that many of us take for granted– that writing is a process and requires brainstorming, drafting, revising, editing–and makes it new again by considering the “physical, material, and located dimensions of processes.” In other words, Rule is interested not just in how writers get from ideas in their head to a finished product, but in how the physical world enters into that process. As she puts it in her article “Writing’s Rooms,” she’s interested in “the environmental minutiae of where writing takes place—the walls, desk, objects, and tools; the bodily movements, interruptions, and sounds of keys clacking.” Given how deeply Rule has thought about how writers actually write—where and with what materials and through which distractions and at what speed—I wanted to interview her to help me think more about writing and speed and how to get unstuck.

Reddy: My background in creative writing trained me to think of freewriting as a way of accessing the unconscious – something like the kind of automatic writing that the surrealists practiced. The more contemporary version of this is Julia Cameron’s “morning pages,” which Cameron describes as “three pages of longhand, stream of consciousness writing, done first thing in the morning.” Many of the people I know who do morning pages or who use other freewriting practices describe it as something like clearing their throat or running the rusty water out of a faucet until something drinkable comes out. I’m curious how you think about the purpose of freewriting in your own teaching? When you ask students to freewrite, what are you hoping it will do for them?

Rule: I think I’m about to take the scenic route here, but I promise I’ll get to the question of purpose! I became a Peter Elbow fan and eventual freewriting evangelist while I was working on my doctorate at Cincinnati. I was reading a lot of his work; I found his writing so alive and intellectually admirable (he has this way of thinking out loud in loopy but coherent fashion). Elbow’s own struggle with academic writing in graduate school was what led him to freewriting, as a matter of survival really – something to do when doing seems otherwise impossible. Just write and don’t stop. He also came to see freewriting as an antidote; he thought students’ language was deadened, flattened by school. Writers, he thought, should shed all outside influence, silence the noise of others, discover their thinking in their own words.

I found freewriting enabling – in grad school I started writing emails to myself of utter freewriting nonsense about a conference or research paper I was drafting. I still do this. I “wrote” some beginnings and hard parts of my recent book in Google Docs, using the speech-to-text feature (because at times even physically typing felt too hard). I very much like having writing started (I am the living embodiment of that Dorothy Parker quote about hating writing but loving having written). My teaching mentors were always talking about and having us do freewriting too, so it became a big part of the composition classes I was teaching. I dutifully described to my students what freewriting was and what it did; I learned about directed freewriting and “center of gravity” to help students work with their freewrites.

I was always curious, though, about what my students were actually doing when I gave them freewriting instructions. I’d basically stare at them, sneak looks over their shoulders, examine their facial expressions, speak to them like a yoga teacher to urge them into a “free” state of mind. Are they really riding the waves of language or were they crafting sentences that answered my question, that satisfied my expectation? This is what lead me to my 2013 study of a freewriter and to affirm that that freewriting is far from natural, easy, or automatic. I think of it now more as an invitation, a deliberate habit. If it’s tapping the unconscious, it’s a repetitive, express, intentioned effort to do so. And we’re never free as writers, of influence or fear or others. So I find myself more actively these days trying to push writers to write on their toes, to subvert the assumptions they have for writing (especially writing in school, that it must be careful, developed, deliberate, correct). I tend to prompt freewriting-type exercises now more with pace (quickwrites) than with “freedom.”

Reddy: In your article on freewriting, “The Difficulties of Thinking Through Freewriting,” I was interested in the moments when you had to intervene to coach your student about what to write. It made me think about what we believe freewriting is doing – especially as opposed to other practices that might help us come up with or clarify ideas, like talking or doodling or visualizing, or even just thinking without committing anything to paper. Why is freewriting such a canonical part of invention, and why do you think talk is more often reserved for revision? Is this primarily about how we think about ideas, property, individual genius – or are there other things at play as well? (Perhaps there’s just not been a Peter Elbow of brainstorming chat, for example. ;))

Rule: Yes, more Peter Elbows! I think that part of the value of freewriting is in the volume of tries you get at articulation, the chance that you’ll discover a phrase or word that can be lifted out as a seed to continue growing in a draft.

And yes, I agree, freewriting and invention practices (like cubing or webbing) reinforce writing as a matter of words and individual brains in isolation. At the same time, many teachers of writing have stretched this idea for me – I’m thinking of Patricia Dunn’s Talking Sketching Moving: Multiple Literacies in the Teaching of Writing, Sondra Perl’s Felt Sense: Writing with the Body, Karen LeFevre’s Invention as a Social Act. I’ve definitely made invention more social, I think, recently: with my research writing students, I do an activity where we all write a potential research question on a sheet of paper anonymously. We pass our sheets, read what’s there, and add a totally different question or reframe one already written. We repeat this passing and adding many times. I compile the sheets as a book of potential, and we return to it in various ways as students eventually commit to a project. Mostly I like how this practice prevents students from deciding their direction too soon – often freewriting and other invention practices too quickly close off possibilities and crazy (good) ideas!

Reddy: One of the things I’m trying to figure out across this series is what we mean when we talk about productivity in writing – and speed is certainly part of that. Part of the reason why your typing video stuck with me so much, I think, is that it really resonated with something I was trying to teach myself at the time – that writing actually isn’t typing, or that it’s not just typing. I often have to move from computer to notebook or post-it note, or get up and walk around until I can think better – and sometimes that thinking better takes actual time, like months or years. And part of what’s interesting about the freewriting protocol you describe in your article is that it does actually insist on some amount of speed, or at least fluency: writers are told to not stop writing, even if they don’t have anything to say, but to instead write something like “I don’t know what to say.” So I’m curious how you think about speed and fluency in writing, perhaps especially in freewriting or invention, but also across the writing process. What does your research show about the impact of continuing to just write, even if you don’t know what to say?

Rule: In those hands-to-keyboard recordings, I think I was trying to see some of the most basic movement of writing but also, as you say, acknowledge how terribly limited that view is. Writing isn’t just in the space between fingers moving and fingers stopping. I’ve talked about this in my research with what I’ve called “romping.” Writing isn’t contained in the mind or in the relay between mind and page; it rather romps all over – into cars, classrooms, night shifts, nurseries, showers, walks, laundry, chats, everywhere! But romping is pretty antithetical to how we tend to picture productivity – when does writing as romping tip over into procrastination or avoidance?

There is something to that freewriting mantra, just keep writing. But I think it’s in a wider-reaching momentum. There is this great book, Understanding Writing Blocks, where the author Keith Hjortshoj talks about writing as a nonstop invitation to stop: writers can stop at any time; they can stop after a sentence or word; after a bad review or an uncomfortable blocked session, or simply in favor of doing something else. Successful writers, Hjortshoj says, are those that have figured out how to stop stopping, to make a habit of not stopping. I think that’s brilliant. The trick is to first spin the plate of writing fast, and then keep it going.

So I’ve been thinking about the virtues of sometimes “hurrying up.” In writing instruction, going fast isn’t something we value basically at all. I mean, the whole paradigm of teaching writing as a process was the recognition that writers need more time, lots of time and space to draft and develop what they want to say and how to say it. But I think sometimes hurrying up is good! When I first start a project or revision, it’s best when I hurry up and start right away, without thinking about it. Avoiding delay makes continuing to write feel much less Herculean. In my classes, now I often time writing activities: I give a question I want to start discussion with, I ask students to turn to their neighbor and see if they can name two potential answers in 30 seconds. For invention in my personal essay class, I ask students to list 10 things that bother them in 60 seconds. The point isn’t if we can meet the goal; the goal is attempting to beat the clock. Writing feels weighty and serious, but I think this no-stakes hurrying can be a good way to trick us into creativity or into saying something we wouldn’t have otherwise.

Reddy: You’ve spent years and years now researching how other people write – and of course, you’ve also been doing your own writing all that time. Could you talk about your own writing process, and perhaps how researching process and the materiality of process has shaped how you write? And since this is a series in part about getting unstuck – what do you do when you’re feeling stuck in your writing?

Rule: One of the coolest results of my research is the responses. People have confessed things to me about the weird things they do, about what they can’t write without. I love thinking about this stuff. And certainly I have considered my own ways—I am, for example, a writer who needs minimalism whereever I am. I cannot bring myself to even deal with books I’m quoting (all of my reading has to be separate and compiled into notes).

I’ve also come to appreciate, though, that what we alone do as writers, or think we do, is only a tiny sliver of what’s going on when writing is emerging. Process is about habits, arrangement, curation but it’s equally about accidents, improvisations, making do, catching a little time to jot while we’re waiting on line or at the mechanic. Processes may be more reaction than ritual or control, more a team sport than a solo performance.

Reddy: Now that you’ve completed your first book, what’s next? What’s happening in your writing life?

Rule: I’m recharging after the book! I’m also early on in a project on annotation as writing (rather than a private record of reading). And in my teaching, I find myself worried a lot these days, about the stakes of everything: how can we move the needle on information literacy, combat fraudulent news and misinformation, undermine the impoverished ways we “debate” online and in media, resuscitate evidence and agreed-upon facts? Who will tackle these issues if not writing teachers?

—

NANCY REDDY is the author of Double Jinx (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a 2014 winner of the National Poetry Series, and Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Gettysburg Review, Pleiades, Blackbird, Colorado Review, The Iowa Review, Smartish Pace, and elsewhere, and her essays have appeared most recently in Electric Literature. The recipient of a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and grants from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Sustainable Arts Foundation, she teaches writing at Stockton University. She’s working on a narrative nonfiction book about the trap of natural motherhood.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)

NANCY REDDY is the author of Double Jinx (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a 2014 winner of the National Poetry Series, and Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Gettysburg Review, Pleiades, Blackbird, Colorado Review, The Iowa Review, Smartish Pace, and elsewhere, and her essays have appeared most recently in Electric Literature. The recipient of a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and grants from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Sustainable Arts Foundation, she teaches writing at Stockton University. She’s working on a narrative nonfiction book about the trap of natural motherhood.

NANCY REDDY is the author of Double Jinx (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a 2014 winner of the National Poetry Series, and Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Gettysburg Review, Pleiades, Blackbird, Colorado Review, The Iowa Review, Smartish Pace, and elsewhere, and her essays have appeared most recently in Electric Literature. The recipient of a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and grants from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Sustainable Arts Foundation, she teaches writing at Stockton University. She’s working on a narrative nonfiction book about the trap of natural motherhood.