W.W. Norton & Company

384 pages

Review by Désirée Zamorano

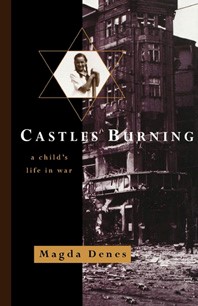

The Girl Who Lived

Nearly twenty years ago I picked up Castles Burning, A Child’s Life in War. It seared me as I read it; I did not put it down until I had finished it. Since then, each time I hear of war in the world, whether in Syria or the Ukraine, the Boko Haram or Iraq, I think of it again.

In the opening paragraph Magda Denes recounts how she as a small child begged for stories from her older brother, Ivan, stories they both loved: “The tales were always intrinsically just. They progressed from peril to joy; they spoke of an ordinary predictable world, where the virtuous were rewarded and the wicked were punished…Losses were restored and the near dead revived. Lack of caution was not a fatal error.” The author has announced precisely what this tale will not be.

Magda Denes’s ferociously unsentimental memoir starts in prewar Budapest in a Hungarian family of nearly aristocratic proportions. Within pages we watch the secular Jewish family move swiftly from a household of more servants than family members to the impoverished tenement apartment of Magda’s begrudging grandparents. The reason for this sudden change of lifestyle? The father sold all of their possessions to pay debts, buy 12 suits, 45 shirts, as well as first class passage for himself, and himself alone, to flee to America. From this first abandonment, our hearts are with this little girl.

Gifted, fierce, protective, and with a deep adoration of her older brother, who at one point is a member of the Zionist resistance group Hashomer, she observes seven years of events unfold with a clear sightedness unmatched by the surrounding adults. Self-involved yet self-aware, we watch her life shrink and expand and shrink again through a tuberculosis sanitarium, the horrors and deprivations of the war, the terrifying “liberation” by the Russian Army, and ultimately as a shell-shocked, traumatized refugee.

Throughout there are startlingly vivid details of this long ago life. Starving, she declines an offer of food at an elegant home because her brother had taught her that it was rude to accept. Hidden above a floral shop, (again, she feels abandoned) she is forbidden to make noise, to even scratch her head. She remains silent, and instead of scratching tallies up the numerous lice that have infested her scalp. Although absent, the impact of her father’s arrogance and highhandedness with those he considered inferior comes back to taunt the Denes family as they reach out to others.

Food is a dramatic presence: her grandfather makes chewing a mouthful of raspberries into a public rebuke of his unloved wife; a gesture of kindness and conciliation turns into projectile vomiting. A son, returning from the camps, transforms his first meal home into a Kaddish; an unexpected feast in Spain curdles, as more courses arrive, from happiness into sorrow.

We have moments of lighthearted glee, as when Magda is the beloved center of attention of Ivan, as well as Ervin, her cousin. And we hold our breath as we read, knowing it would be impossible for all the family members to survive. Who will die? And how will the survivors, how will Magda endure it?

She will endure, with an angry dignity, with a fascinating and admirable ferocity.

Anger is her weapon, and she wields it against those she despises as well as those she loves. It gives her satisfaction, but it fails to console her. In postwar Budapest, isolated from her classmates she thinks,

“Loneliness is always spoken of as a matter of lack. But loneliness is also a condition of surfeit. It is too many runaway thoughts, too great a pull of gravity, too much attraction to the grave, too many shadows that turn into shades, too full a moon on which to wish in vain.”

Magda, Magda, there are so many times your story moved me to laughter and tears in the same sentence. I wanted reach out, to console you, to offer hope, but you hated pity and the need for compassion. You wanted only what had been taken from you.

It is because of this book that a Hungarian Jewish girl is now a part of me. I think of her rage for survival, then I glance at the news. Open the covers of this memoir and you will not be able to stop. When you have closed the book against the harrowing story within, lift your gaze around you. Where is the child you can help, right now?

***

Désirée Zamorano is the author of <em>The Amado Women.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)