(Alan Squire Publishing, 2019)

REVIEW BY RISA DENENBERG

—

In a poem titled “on the road,” Reuben Jackson introduces a motif that recurs throughout his new collection, Scattered Clouds: New and Selected Poems (Alan Squire Publishing, 2019). This poem—the first one in the book—tells the story of black family taking a car trip in 1959, in which the son convinces his dad to stop for the night in Columbia, South Carolina, at “the frontier motel,” but then, it takes this turn,

It worked,

So why did he return without

room keys?

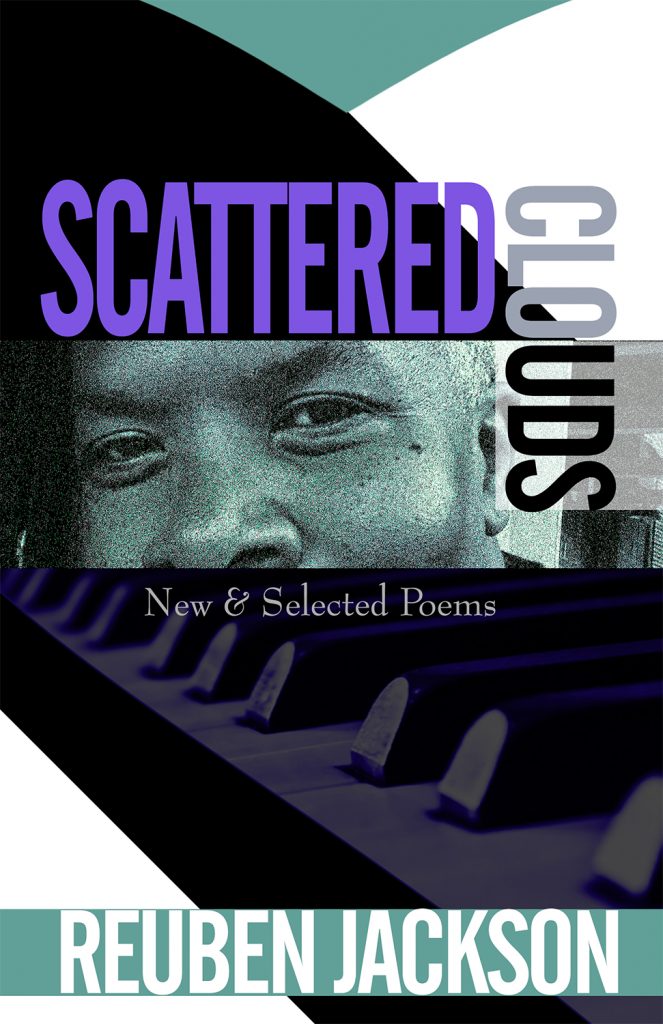

In his sixties now, Jackson possesses a formidable curriculum vitae, with overlapping careers as music scholar, jazz archivist, teacher, mentor, radio host, and poet. Scattered Clouds mingles poems from his first collection, fingering the keys (Gut Punch Press, 1990) with newer poems, creating a tome that is both retrospective and contemporary.

The title, Scattered Clouds, seems to suggest free movement, which is in synch with the many poems that feature jazz musicians—Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Gato Barbieri, Johnny Hodges, Big Mama Thornton, Ben Webster, among others. These poems are a history lesson in 20th century jazz and funk. Reading them, I felt well-schooled. In the poem, “thelonius,” about jazz pianist and composer Thelonious Monk, Jackson offers this reflection,

bizarre?

mysterious?

i say no.

for he swung like branches in a march wind.

reached down

into the warm pocket of tenderness.

Scattered Clouds also suggests a sheltering sky that is overcast with shrouds of racism, suicide, and brutality. This more menacing aspect is evoked in many of these poems, for example, the poem, “Key West,” where Jackson again portrays a youth traveling in the South with family, in which the young speaker notices a white woman, and is admonished by his mother,

. . . to turn my eyes

Toward Heaven

Where it seemed

Even the sky and clouds

Sat

Apart

The book’s first section is comprised of the poems from fingering the keys. These poems are intimate, revolving around childhood, family, neighborhood, school, and a mounting awareness of black musicians, black music, and black political struggle. The interesting, rather than affected, use of no caps throughout fingering the keys confers an ethos of authenticity to these poems (democracy with a small ‘d’), as if Jackson is saying: These are for me and you, I will sing if you care to listen. His language, always accessible, is graceful and emotionally powerful.

In the book’s second section, “2: city songs,” Jackson returns to the many of the same motifs, often captured through a wide-angle lens. In “white flight, washington dc, 1959,” he recounts,

no more playmates

staring

quizzically

at the negroes

on my father’s

album covers

sarah goldfarb

reminded me

of a girl i saw

in an old mgm movie

even though her father said that

like my crush on her

was impossible

Jackson was raised in Washington DC. His year of birth—1954—was the same year the Supreme Court ordered desegregation of public schools throughout the U.S. Of course desegregation has never achieved integration or parity in education for black children. Still, it is notable that DC schools were among the first to implement the Brown v. Board of Education decision, and so, for a while during the late fifties (prior to ‘white flight’) public schools in DC were integrated. I am a Jewish woman born in DC, who also attended DC public schools in the fifties. Jackson’s poems about his childhood make me feel we might have been classmates. You could substitute risa denenberg for sarah goldfarb. We have all suffered the effects of segregation, a point I think Jackson makes most eloquently here, just as he describes its most insidious effects on African Americans.

Consider these devastating lines from “thinking of emmett till,” where the speaker’s experience brings the lynching of Emmett Till to his mind,

stars winked

above the diner

where I asked

a blonde waitress

for sugar,

and got

threatened by

a local

with

bloodthirsty

smile.

The last section of the book, “3: sky blues,” contains a sweet surprise, a delicious and light dessert after a nourishing, but somewhat heavy, meal. To appreciate the origin of these poems, you need to know that for several years, Jackson relayed stories about his friend from Detroit, Amir, via Facebook posts. In an introduction to this section, titled “Amir & Khadijah: A Suite,” Jackson describes how he “first met the late poet-barber-romantic curmudgeon, Amir Yasin, at a party,” and “in the spring of 2017” Amir “met Khadijah Rollins.” They fall in love, Amir writes some poems, and the couple was “not so secretly married.” We are also told that “Sadly, Brother Yasin died in his sleep in early 2018.” Jackson concedes that he shares a birthday with Yasin, and claims that it was Khadijah who “thought it would be nice” to include “a few of Yasin’s love-struck musings.” Whether Amir was a poetic persona or an alter ego, whether the romance was actual or imaginary, hardly matters. I can’t help but wish that I had followed Jackson’s social media musings.

There is a tonal shift in Amir’s poems that we don’t find in Jackson’s. They are short and lyrical— and downright romantic. From several poems titled, “Dearest Khadijah,” we find these lines,

To touch your face is to

Feel my fingers pray.

And,

She is a buoy

in the harbor

at dusk.

In this section we also find this Jackson-penned poem, titled “For Trayvon Martin,” in which the speaker-as-angel walks 17-year old Trayvon home from the store with soulful tenderness—an act which is also a prayer. It ends with these two stanzas:

We shake hands and hug –

Ancient, stoic tenderness.

I nod to the moon.

I’m so old school –

I hang until the latch clicks like

An unloaded gun.

Abashedly, I admit that I had not read Jackson prior to reading Scattered Clouds. But that is exactly why this compilation of poems from his first book with the two sections of newer poems is such a gem. If some of the poems are familiar, you will nod as you read them. And if not, you will feel like you’ve been missing something. Scattered Clouds further establishes Jackson’s role as a steward of Americana.

—

Risa Denenberg lives on the Olympic peninsula in Washington state where she works as a nurse practitioner. She is a co-founder and editor at Headmistress Press; curator at The Poetry Café Online; and has published three full length collections of poetry, most recently, “slight faith” (MoonPath Press, 2018).

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)