(Smiling Mind Documents, 2020)

REVIEW BY CLARA B. JONES

—

They were parents, but when?

And were they considered sourced

or let go on account of victory

sounds like a damp accompaniment

regardless of how great it felt

as one who had never experienced

at least there’s no screaming alone

over stints; it’s a thank-you

you rummaged

in an ice bucket for and found water.

J. Gordon Faylor (2020, p 56)

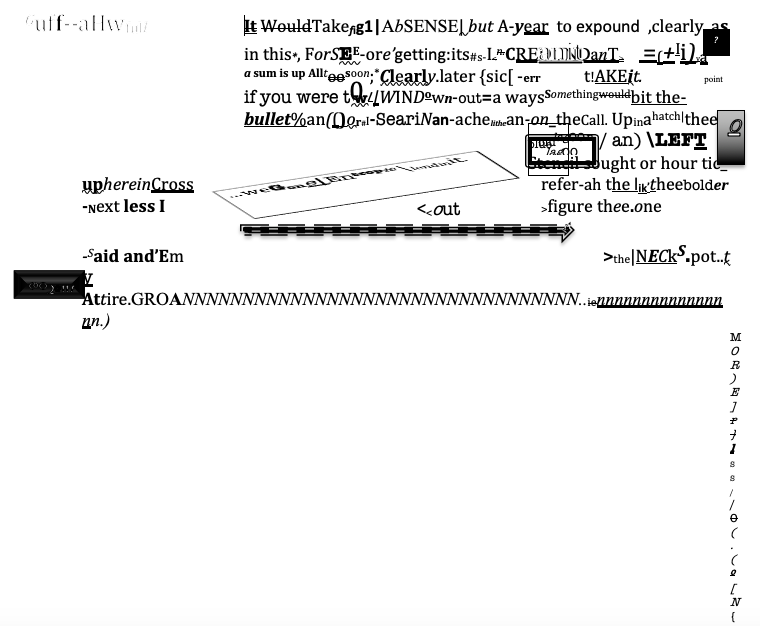

J. Gordon Faylor, Editor-Publisher of the online platform, GaussPDF, is the author of several books, as well as, a few collections in association with his colleague, Brandon Brown. Of particular note is Faylor’s 2016 novel/long poem, Registration Caspar (Ugly Duckling Presse), a collector’s item and a brilliant example of innovative writing that is, at once, a “transrational” experience and a psychological journey for the main character and the reader, alike. In my review of this book I asserted that, “The interpretation of Registration Caspar that I advance…represents my subjective experience as a reader of the novel. I do not claim to understand Faylor’s serious or playful intentions; however, I am of the opinion that the book is both serious and playful as a work of art.” I would make a similar claim about Antoecians, Faylor’s new volume of experimental poetry. Asked to reflect on his collection, the writer stated [via email], “I suppose I’d just note that it’s very much a work made in a state of quarantine, and which comes out of protracted solitude and frustration in and with that solitude, but which I also see—however abstractly—as the kind of concluding book in a trilogy that also includes People Skulk and Want [both available from Lulu.com]. Hesitant to speculate more on how they’re connected beyond sheer chronological proximity….” Herein, I will provide obligatory commentary on what I mean by “experimental” poetry, as well as, discuss Antoecians as an exemplar of Postmodern innovative, avant garde writing that expands our understanding of what associative, “collage,” and political poetry entails.

The word, “antoecians” can be [over]simplified to mean entities existing in separate, though, not unassociated, spatial domains, like the discontinuous yet distributed landscapes that the collection under review represents. In a 2012 essay, the Stanford poetry critic, Marjorie Perloff, a promoter of literary experimentation, advanced the idea that, “in recent years, we have witnessed a lively reaction” to the culture “of prizes, professorships, and political correctness” by a growing group of poets “rejecting the status quo.” In characteristic fashion, Perloff goes on to create a binary between poetry with and without traits that we generally attribute to the lyric, in particular, the personalized, “I,” as well as, music. One might argue that the poems in Antoecians lack the formalized musical elements that the mainstream reader expects [but, see below]. However, such an assessment—a standard—begs the questions: What do we mean by “music?” and Can we re-frame “music” in a manner that is consistent with poetry as an artistic enterprise rather than as an “ism” with invariant definitions and boundaries? As a student of experimental literature who regards Formalism highly, I am always curious about the seeming “tug-of-war” between conventional poetics dominating our narratives about “good” poetry, on the one hand, and poetry that challenges, even, opposes, received wisdom about what a poetic masterpiece should be, on the other.

In her consideration of a lyrical : experimental divide, Perloff highlights questions fundamental to the ways that form, content, and meaning are understood as literary criteria. For example, the esteemed critic raises these questions: What makes a lineated text a poem? Does a poem require some sort of closure or circular structure characterized by a beginning, a middle, and an end? Should the poet speak via her/his/their own “person?” Should the poet divulge intimate, autobiographical details? I suggest that, like the poems in Antoecians, the avant garde poem can meet formalist standards [if that is a valuable pursuit at all] if we view words, phrases, sentences as units of wholes [whole poems, whole compositions, whole structures] capable of standing on their own not only as units subordinate to and secondary to the whole. Such a re-framing of what we mean by a poem raises elements, components of the whole to levels equivalent to the whole that exist on their own terms capable of standing alone or as parts—in combination with, even, greater than, the sum of the parts of the whole—a [literally, politically] radical transformation of a hierarchical into an egalitarian form or structure. Such a redistribution of the power of parts—of words, phrases, and their additional combinations [and re-combinations]—provides a bridge from the grand conceptual frameworks of Modernism [Marxism, Psychoanalysis, Capitalism, “Genius,” Utopianism, Idealism] to the “fractured,” fragmented, even, relative, realities and landscapes of Postmodernism, as exemplified by the poems in the volume under review.

Importantly, if we are to argue that Faylor’s compositions are not inconsistent with—if not, actually, continuous with—the poetry of Modernism and the rules of Formalism, and that Faylor’s text is anti-establishment, but not a rendering of anti-fascist or anarchic literature, it is necessary to demonstrate that Antoecians is a collection of rule-governed poems—a formal property that can be viewed as choices and as “intentional,” to employ Perloff’s term that she used to argue that Conceptual poetry is not “uncreative writing.” This perspective is not intended to suggest that Faylor selected or wrote each word, phrase, etc. in a conscious, aware manner. However, it is to suggest that Faylor’s consciously or unconsciously positioned elements, components lend cohesion to the composition itself—a form of literary integrity. In experimental writing, repetition, classically represented by the writing of Gertrude Stein, is widely acknowledged to be the most recognizable “glue” or technique unifying an experimental, avant garde collection. Faylor’s repetitive method is apparent on every page, in every stanza, of his new volume—repeating words comprised of double-letters, resolving what might seem to be a paradox between whole and part or between unfragmented and fractured. Perloff might see this as a trait or flavor analogous to what she calls “circular structure,” characteristic of conventional writing [see paragraph 3 above]. However, though I am in constant search for evidence of formal characteristics in experimental writing, Faylor would probably discount or, even, dismiss, any significance such comparisons may seemingly embody.

Other intentional or “rule-governed” features of the compositions in Antoecians, permitting fracture to coexist with unity, are word play [Ludwig Wittgenstein], including, the creation of neologisms, methods employed—apparently, but, not necessarily, consciously—to generate novelty, expanding parts and wholes—virtually, creating new forms and meanings. Thus, “Windatry Dontcry. Your amyxial Slaty-Gray;” “Was the leg-dump Thermaltake;” “the dim boat Scramsilence;” “the planet ruined people I saw as empaths.” Off and on throughout the text, Faylor repeats sounds: “godwit;” “sunlit;” “unlit.” With these and other techniques, Faylor combines and recombines form, content, and meaning—creating independent, as well as, interdependent, functional units. Other traits include the occasional incorporation of conventional elements, components—possibly self-referential material—[“As before, as foretold, I doze off at work. I make less money than I did before.”; “an already simple Oakland worry makes”]; beautiful images [“imagination gone corpulent”]; emotion, including, loss and love [“couldn’t read that for years after you left”]; and, on p 14, lines can be found that approximate music—or, rhythm, for sure.

Other features of the poems in Antoecians expose the hand of a professional, rather than, an amateur writer—a serious, highly-evolved poet with a mature, “intentional” poetics. In particular, not only, repetition, but, also, one- and two-syllable words, as well as, hard consonants are employed to full artistic effect, resolving—or negating—another seeming paradox between balance and skew—again, whole : part or unfragmented : fractured. I find Faylor’s deference to the political to be, particularly, noteworthy—the establishment of an understated, non-intrusive, respectful relationship with his readers by placing “interpretive power” [as per Formalist, Helen Vendler] in the reader’s person—a solidly Postmodern methodology. To the extent that Antoecians can be said to embody [fractured] content, as well as [fractured] form, meaning, also, is a function of the beholder’s body and mind via sensations, feelings, emotions, thoughts, images, associations, and abstractions stimulated through interactions with words on the page—not necessarily contiguous elements, components on contiguous pages. Finally, though I recommend Faylor’s new book, especially, to those who are experts, students, or consumers of—or who are curious about—experimental writing, broadly defined, this collection will appeal to any reader who values literary invention and an opportunity to engage with art of a high, though not rarefied or pretentious, order. In addition to Faylor’s other works, Antoecians deserves a wide audience.

—

Clara B. Jones is a Knowledge Worker practicing in Silver Spring, MD, USA.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)