WORDS BY ANDY MARTRICH

“Le temps et le monde et la personne ne rencontrent qu’une seule fois.”

– Hélène Cixous, Dedans

In the 1996 novel Pussy, King of the Pirates, which is a rendering of Treasure Island, Kathy Acker documents the exploits of a timeless Antigone as a surrogate of Stevenson’s protagonist Jim Hawkins. Through a mesh of narrative voices, Acker disputes the validity of time as a categorical imperative, suggesting that its necessity in the adventure of “buccaneers and buried gold” is coupled with its role in sustaining a patriarchal dogma that inflicts trauma indefinitely:

Out into the future, what will be time. In this arena between timelessness and time, the most dangerous thing or being that can come into being is time. (68)

The present, as the embodiment of a certain perniciousness, contains traces of its assemblage alongside the implication of its intactness. Although this appears intrinsic to its archival disposition (i.e., as a palimpsestic record), this symbiosis likewise connotes its fragility, since that which appears dynamic (as the result of things having happened) only does so by both succumbing to and imposing limitations that are otherwise transitory. Acker presents this idea in a narrative continuum, where things documented aren’t necessarily taking place within a chronology. Compliance to time refracts as the indulgent rationality and morality of a particular (male) sympathy. As an impetus filtered through privilege, it adheres to deep-seated preoccupations with rules that have the semblance of coming from nowhere, yet are blindly reiterated by cryptic authority.

Teresa Pepi’s L|in|P;L|in|D;L-o (Gauss PDF, 2015) confronts time as a similar snare, albeit with born-digital connotation. Contextually, Pepi makes use of Gauss PDF’s blog format (i.e., Tumblr) and publishing structure, which enables one to present files in lieu of normative art/poetry productions, allowing for the construction of new models and the supplementing of older ones. L|in|P;L|in|D;L-o is a zip file containing three Microsoft Word documents and forty-six jpegs. Most of the files are labeled by page number (although some pages are missing) and a succinct, generic title. The blog post itself contains a preface/personal note, which cites grim indicators. Even before opening the zip file, time is characterized in a reductive sense as the brutality of entropic order that portends an interior agony. It simultaneously coerces interiority while encompassing it, granting it an exploitative creative omnipotence. Yet, in lieu of its sinister, violent, and powerful character, time is susceptible to its own deterioration; it’s in disassociation from time (perhaps in its complete decay) where we might slip its terror.

The initial document in the zip file contains a poem titled “Drive.” There’s a loose employability, as it (along with the other two Word documents) is left to the possibility of editing, changing, and even redistribution. It also provides anatomical continuity to ideas expressed in the preface by reflecting the implied malleability of an “inbetween”—an undecidability that churns within an association of certain dualities (e.g., clean/dirty, health/disease, identity/anonymity, etc.). The poem is rant-like, while at the same time incurring a detached lucidity:

What do I look like, I don’t look like anything

the vehicle is the window, time is the window

drive to become clean, but you need to change

I am the window, I get dirty, you get clean

I enter the crowd

the bacteria entered the window pretending to be clean, the new space is diseased

locate the disease, find the source

trace the trail

but now yourself is diseased

you yourself must go through a window

to get clean

[…]

the window through the window to be clean, time through time to undo it

“Driving” expresses an active energy—a propulsion through time and space within a place of confinement (i.e., the fragile interior of a vehicle). In general, it connotes inadequate escape, as it can only reframe the complications at the core of locality; one inherently brings one’s own time and space into the time and space of others. There’s mutual exchange of contamination (the worst things have already infiltrated), yet Pepi must get through the window, identified as both the self and time, in order to avoid all corruption. Pepi must access the intermediacy of contrasting conditions.

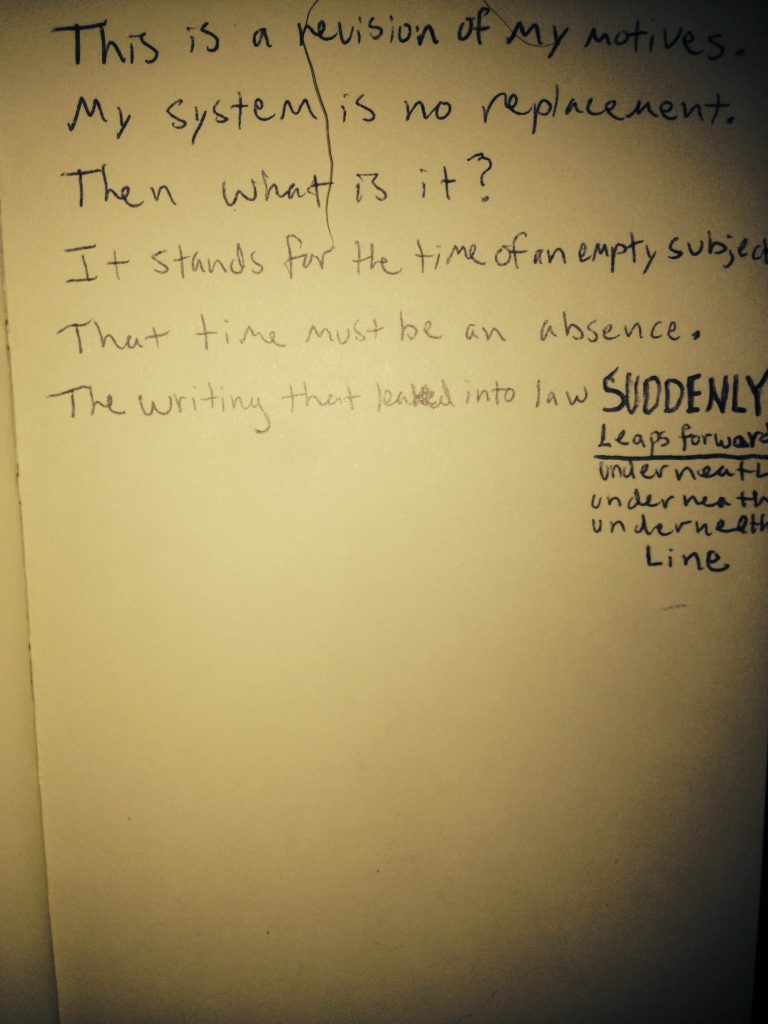

“Driving” is followed by an unsettling jpeg titled “Multiple Revisions (1),” an image of text scrawled on a wall in a dark room. Here, Pepi refers to time as “an absence,” which suggests that withdrawal from it can’t be as linear as a process of driving:

In lieu, unhinging from time requires a kind of presence. The revision of Pepi’s “motives” rescinds the proclamation that one must propel into the “inbetween,” but rather dive beneath it. This idea is bolstered by three “Lint Paintings,” minimal portraits of a small gradient immersed in a vacant landscape. The lint paintings impress contemporaneous releasing/compressing—as if floating in a vacuum, or drifting into a kind of microcosmic, isolated realm. They appear to be topographical, delineating the locality of time as it occurs in hypothetical blankness as a speck of dust. Time (as lint) is small, gray, and spectral—yet connotes a portal out of scale, a puncture leading to material abyss. Eyes are drawn to it; one follows and resides in it.

Sure enough, we next encounter Pepi on the inside, or rather in the “Inbetween Space,” the first of three jpegs depicting a process of self-burial. “Inbetween Space 1” is an image of Pepi half-buried in the ground, reaching out to a nearby wall with dirt-caked fingers. Pepi appears trance-like, as if in communion or contact with something otherworldly. There is heavily contrasted golden light and deep shadow, with the latter descending through Pepi to the wall. Again, we come upon muddling dualities (e.g., light/dark, hidden/exposed, etc.), represented here by Pepi’s body. This is followed by “Inbetween Space 2,” an extreme close-up of the unoccupied hole, suggesting the reversal or disorienting of time, perhaps the effect of Pepi’s transfer, as self-burial takes place out of sequence (“Inbetween Space 3,” which shows a blurry figure (likely Pepi) digging the hole, is found at the end of the zip file).

With Pepi wedged in the gateway, L|in|P;L|in|D;L-o flickers in and out of time’s sadism, where technological authorities—including language—start deteriorating. Duration is in a process of annulment, affecting any kind of historic regulation. In a note to J. Gordon Faylor (publisher of Gauss PDF), Pepi comments:

There’s this thing in which one’s own personal life is allowed to make sense only through addressing the past without an image of it. You can’t have legal documents in other words. So I had to make them up.

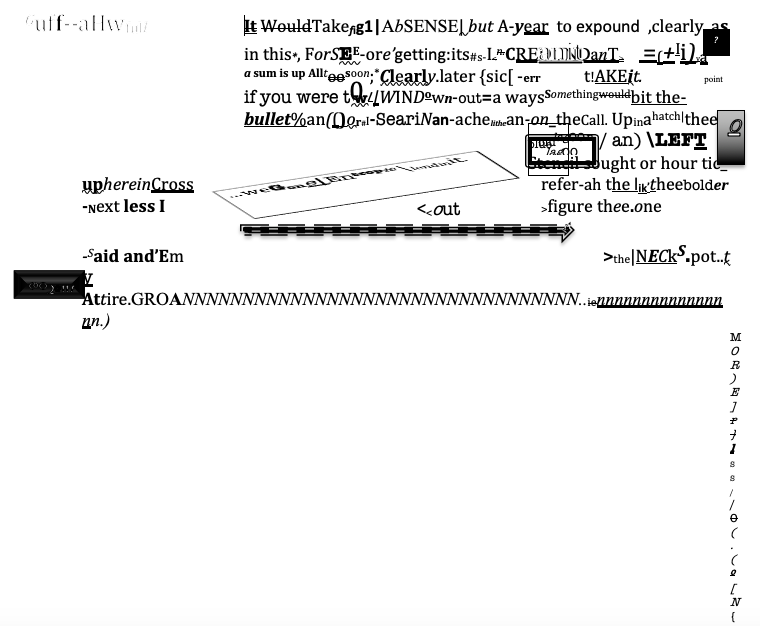

One refracts former and prospective selves, experiences, relationships, and traumas into an imageless void. Indeed, Pepi constructs legal documents from this space—fabricated legalese composed of garbled text and symbols, perhaps reminiscent of spam, code, or found language. Legal documents are situated around the jpeg of the hole, connoting an extraterrestrial (non)communication via mystical expression or an arcane symbology (although rendered through a familiar filetype) from the “Inbetween Space” itself:

With the thread of authoritative evidence in peril, the delusion of the rule-based self-as-result is confounded by the breakdown of time. The legal documents are the last “texts” we see. There’s no longer a language, or any device for that matter, through which to recognize time’s jurisdiction. Pepi articulates its absence in a hiccuping continuum of digital photographs. Easily the most extensive part of L|in|P;L|in|D;L-o, thirty-nine of its forty-six jpegs are dedicated to a nearly identical shot—what Pepi refers to as “Overhead Light,” a ceiling fan and lamp framed from the same angle in varying light and shadow. The images are for the most part labeled in order (i.e., “Overhead Light 1,” “Overhead Light 2,” etc.), aside from a few missing numbers in the sequence. Yet like the “Inbetween Space” photos, they don’t seem to follow any particular duration beyond how they appear arranged in the zip file.

Many of the images include ghostly backscatter, implying spectral presences. One gets the sense of claustrophobic domesticity—that of being trapped or hiding in a room. The repetition and eeriness of a common household object suggests something conspiratorial at play, drawing parallels to Lynch/Frost’s use of the ceiling fan at the Palmer house in Twin Peaks, which is cryptic enough for fans of the show to speculate numberless roles, although most certainly embodying an essential function regarding the on-going violence, trauma, and ghoulishness of the series’ narrative. Pepi’s “Overhead Light,” on the other hand, appears to be more deliberate regarding its apparent inertia, although, once again, blurring the boundaries of chronology. But given the monotony of imagery and implicit paranoia (as to what is happening off camera), what are the effects of Pepi’s transfer to the “inbetween”—is Pepi liberated, captured, or none of the above? And where does that put the reader?

In L|in|P;L|in|D;L-o, time is a cliché that produces, compartmentalizes, and enacts cruelty within a solipsistic fantasy that ensnares us all. Amid the oscillation of extraneous conditions (e.g., as articulated in gradual disjunction out of time), Pepi appears rhizomatic (as per Deuleuze/Guattari’s conception of it)—planted within the intermediary, rooting and shooting into unknown perpetuity. There’s boundless interconnection in the presence of indefinite possibility beyond time’s snare. Perhaps, then, L|in|P;L|in|D;L-o suggests a peripatetic literature, contingent on activism against a foundational curse. On the other hand, the preface concludes that “this project is about nurturing,” asserting that Pepi found comfort, healing, and solace in the exploits of a self metamorphosed into a timeless Antigone. But with the terrible sadness of Pepi’s passing in 2015 at the age of twenty-one, L|in|P;L|in|D;L-o is not only more painful to revisit but also leads one to wonder if it isn’t an explicit gesture.

Self destruction is what it is

it’s a collective wish that

what is exists

—

Andy Martrich is the author of Ethical Probe on Mixed Martial Arts Enthusiasts in the USA (Counterpath Press), A manifest detection of death-lot in banking games (Gauss PDF Editions), and Iona (BlazeVOX Books), among others. Some essays have appeared at Jacket2, The Volta Blog, and ON Contemporary Practice. Andy works on Hiding Press with Mark Johnson and Jonathan Gorman, and lives in France.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)