(Gauss PDF, 2019)

REVIEW BY CLARA B. JONES

—

“[Elon] Musk holds a substantial monopoly on the contemporary gaze.” s. maynard, musk (musca\muscus\mus)

Stella Maynard is a writer in their early 20s living in Australia, “interested in attending to things that sit at the intersection of gender, queerness, technology, the law and desire.” Their pamphlet, musk (musca\muscus\mus), a semi- “found,” appropriated, collaged, and annotated document (difficult to classify within literary categories or genres), was longlisted for The Lifted Brow‘s 2018 Prize for Experimental Non-Fiction. As the title indicates, the text addresses various philological roots of the word, “musk,” as if they were derived from the person [and, persona], Elon Musk [the subject], the billionaire “techno-capitalist.”

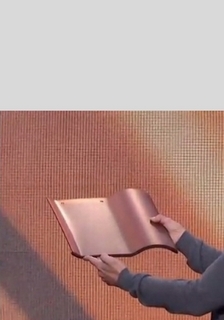

Though unpaginated, the verso-recto format of musk is integral to the pamphlet’s symbolism, significance, and validity as an example of “experimental” and Flarf-like composition since left-hand pages present copies of internet-based material related to Elon Musk—tweets, Google and Facebook entries, photographs—that, in most cases, echo topics addressed on the opposite page. Right-hand (recto) pages present Maynard’s running essay or, perhaps, their long-form prose poem that, because of copious footnotes on virtually every page, reinforces the importance of “found” and appropriated images and text, bringing to mind a comment by the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poet, Susan Howe, “I love the play of footnotes.” By relying upon “found” and appropriated material, Maynard places their work in the company of female writers, such as, Katie Degentesh, Sharon Mesmer, C.D. Wright, and Juliana Spahr.

For purposes of discussion, musk can be divided into five parts—an introductory section, a section on each of the three sub-topics [musca, muscus, mus] and their metaphorical relationship to Elon Musk, as well as, a final, brief conclusion. In the first section, the subject is introduced as “a Man of textual superabundance” due to his constant exposure via social media, the press, advertising, and the like. Maynard goes on to say, “Fundamentally, Musk is infrastructural: a man of tunnels, cars, batteries, energy grids, high-speed trains, giga-factories, wires, and inter-planetary transport.” These associations highlight, not only, the protagonist’s masculinity and phallic display, but they, also, imply his access to power as a symbol of patriarchy. Just as significant, Musk is a powerful figure with whom many men identify and through whom many live vicariously, leading me to consider the manner in which Musk’s attraction may be viewed as a kind of homoeroticism.

The next section expands Maynard’s discussion of Musk “as a trace or index of masculinity” by highlighting the relationship between the subject’s defining characteristics and “musk” (musca), technically defined as testicle, scrotum, as well as, a male sexual hormone. Iterations of the subject on the internet are, in Maynard’s words, “instructive in illustrating the ways in which Musk and his vernaculars of techno-masculinity are habitually taken up, reproduced, and updated, eventually becoming naturalised forms of embodied subjectivity.” This techno-male, then, is a mytho-poetic construct—part real, part fake, part object, part copy, part fantasy—“ready-made” (Marcel Duchamp) for an ubiquitous “neoliberalism.” Throughout their text, Maynard extends their analysis to the roles played by Musk and other techno-masculine figures in perpetuating the destructive, mediating, and dehumanizing effects of Capitalism.

In the third section, Maynard employs the idea of a moss plant (muscus) as an interface between “the plant, animal, and human worlds.” They transfer this fundamental, and powerful, function to the subject, stating that, “Attending to our ‘mossy’ networks necessitates an engagement with the ways in which Elon Musk’s infrastructural developments are changing the present and future organization of life.” Maynard introduces Naomi Klein’s term, “philanthrocapitalism,” referring to “a billionaire class who posit themselves as the problem-solver of crises that have been historically (un)settled through collective action, dismantling or the public sector”…representing “a form of corporate environmental paternalism whereby the ultra-rich ‘generously’ tackle some of our greatest crises using their loose change.” Though it is easy to sympathize with Maynard’s concerns and to validate their analysis, the statements may be problematic for some readers since, from a purely artistic and formalist perspective, their didactic, literal nature potentially detracts from the otherwise seamless flow of the text (which should be read at one sitting for maximum effect) and since the overwhelming scale of current global crises, such as climate change, ecosystem collapse, and poverty, all but require solutions produced by concentrated wealth. Nonetheless, in musk, Maynard presents themselves as a political poet concerned, as Adrienne Rich was, with using the “oppressor’s language” [Rich] in revolutionary ways.

The fourth section addresses “the index of ‘musk’: mouse” [mus]. Again, the philanthrocapitalist is presented as a mytho-poetic symbol of power. Maynard writes, “In August, 2017, SpaceX delivered 20 mice to the International Space Station. In fact, Musk’s desire to make human life multi-planetary began with the dream to send mice to Mars; his intention was that the mice would procreate in space, and return to Earth with interplanetary offspring.” Maynard advances Nathan Eisenberg’s notion of a gendered subjectivity, “discursively infused with a system of values that would reinvigorate the men of the nation to deliver salvation.” Invoking the Futurists as representatives of “the Modern fascist man” (e.g., Ezra Pound), Maynard does not mention the paradox that the Futurist movement, though short-lived (~1909-1920), was noteworthy as an artistic project and was the source of some of the creative techniques Maynard, herself, employs (e.g., verbal collage, “found” material: see Marjorie Perloff, 2003, University of Chicago Press). Nonetheless, philanthrocapitalists are empowered by unregulated markets and [masculine] competition, and, as Maynard puts it, “The quest to make humans multi-planetary represents a kind of pseudo-colonial environmental-fatalism whereby men of the capitalist elite give up hope on their environmental survival, and quite literally abandon the planet they have all but destroyed.” Related to this, the author suggests that these men are having unfettered fun at the world’s expense by way of “a pervasive youthful playfulness.” Power play, then, is a gendered game.

Maynard ends their text (each page paired with one or more found images referencing the subject) implicating “white masculinist possession,” calling, instead, for Jordy Rosenberg’s plea to “summon the counterforce of our own desire.” Presumably, this is a statement concerning the power of feminist principles to forge solutions via a “collective state of lived resistance…founded in scenes of ambivalent desire and intimate attachment…beyond (and against) the pheromonal energies of Elon Musk, directed towards new discursive formulations.” In the final analysis, then, Musk is not a fantasy, or an abstract case, but a real threat, and Maynard focuses their creative abilities upon using art in the service of feminism and politics—nationally and internationally. This debut pamphlet marks this young author as a writer to watch as their artistic talents and political sensibilities expand and mature. I recommend this volume to anyone interested in a creative activist, feminist, and civic voice deserving a wide audience. musk (musca\muscus\mus) provides its readers with a unique visual, symbolic, and literary experience, a worthy example of avant garde collage, conceptual, and appropriated composition, and I look forward to reading Maynard’s future work.

—

Clara B. Jones is a Knowledge Worker practicing in Silver Spring, MD, USA. Among other works, she is author of Poems for Rachel Dolezal, published by Gauss PDF in 2019

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)