234 pages, $19.95

Review by Denton Loving

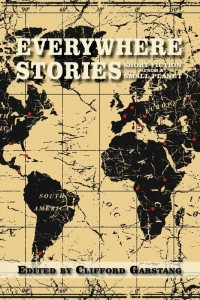

“You just don’t know who your enemies are. And your enemies are so often your friends, Molly. It will always be like this, I fear,” says Lana, the narrator of Alden Jones’ “Heathens,” one of twenty stories collected from twenty different authors from around the world and edited by Clifford Garstang in Everywhere Stories: Short Fiction from a Small Planet.

Lana is an American teaching in a village in Costa Rica. She is well loved by her students and the community, but in the story, she is caught up in teaching a lesson of a darker kind to Molly, a teenaged innocent visiting Costa Rica as part of a group of fly-by Evangelical missionaries.

Lana discovers that the world is dangerous, which is also Garstang’s first thought in his introduction to the collection. These diverse stories range from every continent, from toothless bikers in New Zealand to young women approaching adulthood in the Congo, from a boar attack in a German park to a suicide bomb in Israel. If these stories share a single theme, it is of this danger that permeates our human existence, regardless of our geographic location. Continue reading

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)