REVIEW BY NANDINI BHATTACHARYA

—

“So ashamed of our failed nation, we hide our faces behind masks,” writes Ken Chen in his elegy for a dying nation, “By the Oceans of Styx, We knelt and Wept” (Four Quartets, 91). What does it mean when a mask represents not so much a disguise, but a consensual acknowledgment of existential precarity manifesting in the form of the Nation-State subjugated by a viral pandemic? This is a core question that Four Quartets: Poetry in the Pandemic, an extraordinary bardic chant and threnody for humanity, makes us ‘face.’ The choice to ‘face’ this question with masks on or off, the choice of kind of mask, and the choice of acknowledging that we have already, for some centuries, being living in a society of extreme masquerade is, of course, always ours.

As the editors Kristina Marie Darling and Jeffrey Levine write in their foreword, this has been a year when the iconography and rituals of an actual earlier cultural artifact called ‘the Masquerade’ have returned with colossal force: “an incoming tide of masks literally remakes the faces of every country on earth” (Four Quartets, ix, emphasis mine). Historically, the ‘Masquerade’ was an eighteenth-century European entertainment that was also a tango with danger and a memento mori, in part commercialized by the Entertainment Industry overlord (a comparison to such a personality in our own times feels inevitable here) John James Heidegger, who saw a ‘monetization’ opportunity (as always) in the human penchant for crossing and re-crossing boundaries of purity and danger for the sheer titillation and euphoria of transgressive risk-taking. ‘Masquerades’ became popular nocturnal ‘raves’ in many European cities, briefly but tantalizingly inverting social, sexual, class and other hierarchies and dissolving the boundary between purity and taboo. Naturally, what happened with the mask on had to be left behind at the masquerade, a perfect recipe for a world turned upside down.

A masquerade is a performance, and all performance intrinsically implies a temporary death or at least suspended animation of the ‘person’ behind the ‘performer.’ Besides, masks are intrinsically unsettling because they are the ultimate, uncomfortable reminder that we may never truly know who the person next to us really is. They foreground the idea that any identity is a performance, a kind of deceit or the potential for it. In the eighteenth-century ‘Masquerade ball,’ ‘masking’ as pageant and entertainment entailed not only a flagrant, exhibitionist performance of the instability of all identities, but even a carnivalesque, theatricalized and often libidinous death drive, a macabre one-night stand with death or dissolution. Excess and transgressive frenzy were never far from a melancholic recognition of death as an ‘underworld’ eternally undergirding life, of life as ashes and dust moving toward ashes and dust. A mask is also a metaphor, and all metaphor is, of course, an evocation of the absence of the thing being invoked. It is a reminder of a potentially infinite abyss that could be hiding almost anything. The early modern masquerade and today’s COVID-19 medical mask are both representations of the open-ended implicit consensus that the coming plague might be just around the corner, and so carpe diem. Perhaps in this spirit, in their poem titled “During the Pandemic” Rick Barot points out that “the canvas that was painted uniformly black could be open-ended and be a consensus at the same time. Like a plague” (Four Quartets, 282).

Comparing the eighteenth-century masquerade—a voluntary, often transgressive performance of a transgressive desire for transgressive desire—with today’s medically mandated COVID-19 mask may seem fatuous or cruel. However, while a mask by any other name might always be a public health contract, any mask is always a reminder of the rift between appearance and reality as well as the hopelessly overdetermined site of simultaneous ‘open-ended’ ‘consensus’ that the coming plague is indeed around the corner. The mask’s promise might never be commensurate with its performance. So while COVID-19 masks are one performance of the promise of good citizenship, of modern rationality, the masked look itself is at the same time archaic and riddled with precarity masquerading as safety. Even when the mask is epidemiological best practice, can it erase millennia of the mythos of masking as charade and make-believe (even going back to Greek choruses and Kabuki actors)? This begs the question of whether some Americans have resisted wearing masks and even denied COVID-19 because they didn’t want to be reminded of the essential hollowness of their beliefs and bets? If a carefully orchestrated status quo—’Trump and Pence will Make America Great Again’—suddenly begins sinking into an epistemological sinkhole called a real Pandemic requiring real masks, if we can’t continue to believe that things are as they seem and this is the best of all possible worlds as Voltaire’s Pangloss insisted in Candide, what kind of existential crisis does that land us in, and why should we allow that? Welcome to COVID-deniers.

Poetry in the Pandemic riffs on the COVID-19 mask that so exquisitely reinforces this existential doubt: the approach of the masked stranger or friend signifies, paradoxically, both safety and danger, and friend or foe. In the wake of an explosion of designs and styles in COVID-19 masks—including the infamous and ‘humorous’ ‘death’s head’ mask, for instance—we saw ambivalent staging of such caution always already infected with knowledge of precarity. A death’s head, the quintessential memento mori, works precisely by chaining representation inexorably to what’s represented, forcing sign back into symbol—the skull is death, not just its sign—but without relinquishing the joke, the fun, of the viewer’s ambivalent reception of the full enormity of the cruel joke. Most importantly, moreover, the precarity the COVID-19 mask staged as well as intensified has proven unfairly and exponentially more acute for underrepresented groups in the ‘best of all possible worlds’ in 2020, a point we will soon return to. And it is this plethora of meanings and messages, double-edged and relentless, that poetry in Four Quartets showcases. Poets in word and image—revolutionaries incanting the ‘human condition’—rise in response to the Pandemic’s terrifying reminder of the chasm in the human experience of modernity and progress. The COVID-19 mask is a memento mori particularly in a society where BIPOC Americans are murdered with impunity and also fundamentally precariously situated—some masks are more ill-fitting than others— when it comes to healthcare and all other life-saving and life-giving resources, including the (non-)empathy of a mad (non-)POTUS.

Almost a century ago another bard of the human condition named T.S. Eliot wrote poems collected into another collection named Four Quartets. They covered many of the themes found in this present collection. During the intervening century, the striving T. S. Eliot foresaw hasn’t brought about the salvation and redemption he sought, unfortunately. So his successors try again. Perhaps the editors have consciously collected here poems that formally and thematically invoke the mask that has become the dread hallmark sign of our Annus Mirabilis, CE 2020, or perhaps these poems have collected together—since we, readers and writers cannot—as a cri-de-coeur of a collective unconscious protesting an apocalypse we arrogantly fooled itself into thinking no longer possible for our ‘advanced’ species. Nearly every poem in Four Quartets: Poetry in the Pandemic is an affective diptych hinged on apparently divergent but clearly connected and in fact co-constituent crises: the pandemic of environmentally apocalyptic war against the planet, and the pandemic of socially apocalyptic war against BIPOC, the poor, the chronically ill, the dispossessed, and the disenfranchised.

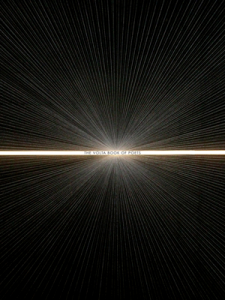

One need only connect pandemics of greed and disease to see them fit together. In doing so, the poems both resurrect and challenge their apparent binary. The connections between environmental and social apocalypse are depicted, whether in disturbingly eloquent words or in the black and white photography of B. A. Van Sise in their collection The Infinite Present, a series of photos recording a Dante-esque infinity of hellish chronotopes, found also in Mary Jo Bang’s poem “The Present Now,” in which every sentence starts with “Today.” Both in Van Sise and in Bang, all those “Todays” add up to an indifferent, infernal eternity and infinity—no yesterdays or tomorrows—exactly the poetic conceit for Dante’s hell. For instance, in Sise’s photos, hell is where looming, lolling figures, damned souls, wait before closed liquor stores in gutted city neighborhoods, evoking by their frail hovering public spaces turned phantom and taken over by a sign saying “Before I Die,” or puppets eating cake at an empty “reserved” café table.

In Jimmy Santiago Baca’s “Buffalo Prayer,” buffalo thunder through cities where streets revert to original canyons, “wombs of cliffs” (Four Quartets 17), “with heat made hooves/ heat-hooves sure as flames/……/ more heat, more hoof, more breath/ more heart/ hoof music heats us back/……/ Buffalos/ All over the city/……./ armored military goon-squads in Bradley tanks/ roam the night/ with orders to kill the four-hoofed creature/ but/ Buffalo are coming/ down the Appalachia trail and Continental Divide/ grinding false patriots beneath typhoon hooves” (Four Quartets 6-8). The alliterative thunder and pant of the verse reminds anyone who’s traveled through the American West and Southwest exactly what this buffalo stampede could look like and mean. Baca’s prayers include that the time of the buffalo’s return will also be “The Time of Gardens” (Four Quartets 19), but with the Corona virus as king, emperor (Four Quartets 17), “When the wealthy/ got on their jets and yachts and hid on their private islands,/ gangster viruses hunted them down and took them out—/ I mean, how radical is that, right?” (Four Quartets 20).

The virus is indeed a gangster, but it also a part of an animistic sacred that imbues landscape and poetry and finally stands up to viral greed and genocidal capital. And like that animal/animus, the virus is also shape-shifting predator for Rachel Eliza Griffiths’ narrator in “Fever” from her aptly named collection Flesh and Other Shelters: “I burn in the frame of me, leaning against dark beams of bone/……/ I am in the teeth of my temperature” (Four Quartets, 195). When the king virus arrives, who then will be inside versus outside, masked versus unmasked, self versus other, living versus dying, occupied versus alienated? Greed and consumption would also do well to think of what they are greedily devouring.

The enjambment of environmentally apocalyptic and socially apocalyptic pandemics is centerstage in Denise Duhamel’s plainspoken diagnosis of the unspeakable collusion of Late Capital and ancient prejudices to destroy both planet and human community because with “George Floyd … the protests began, the best minds of the next generation chanting, demanding sanity from the worst King America who was clearly out of his mind” (Four Quartets, 262). Do, as E.M. Forster said, “Only Connect.” Two pandemics, one crucible. A container for an evil can itself be infected by that evil and thus in the end inseparable from it as an image or idea; the black mask meant to contain the black plague will forever after resurrect the memory of the black plague; effect seems amniotic in cause because cause and effect are actually the same and also successive; so the crowned king of Duhamel’s society bent on exterminating the ‘weak links’ (“the terrible thump of Trump through the wall,” Four Quartets, 261), can also be the virus with a kingly name produced by the very society fatally infected with greed and hatred, at tireless war against nature and life in the name of ‘rational’ thought and ‘rational’ markets.

In such a society, in the room “Where my sisters/ read the news of melting ice-caps/ and the virus named after a crown” (J. Mae Barizo, “Sunday Women on Malcolm X Boulevard,” Four Quartets 110) one is held down head first in learning “how to love the cough, the test/ the social distance, the canceled prom, the empty gym/ The steady slide into impoverishment,” as Jon Davis writes in “Ode to the Coronavirus (Four Quartets 159). That lesson might also hold the answer to Dora Malech’s question in “Dream Recurring”: “This is History. Where are you supposed to be?” (Four Quartets 123).

In Traci Brimhall and Brynn Saito’s “Ghazal that Tries to Hold Still,”(Four Quartets 248) against its very nature, the poem’s fourteener couplets end in the repetitive end-rhyme words ‘shelter’ or ‘shelters,’ giving the verse the hymnal yet balladic quality of the ancient Arabic ‘ghazal’ that spilled worldwide—like a poetic pandemic—via Sufi mysticism, uniting the positive affective diptychs of spiritual ecstasy and wounded earthly love, equal hallmarks of the form. In Brimhall and Saito’s “Ghazal,’ though, the tormented lonely cry of ‘shelter’-in-place demanded by COVID echoes the tormented crying in those other ‘shelters’ where ‘illegal aliens’ are herded by ICE before being returned to familiar circles of familiar infernos. Their torments are not unlike those of the ‘patient’ in Maggie Queeney’s “Origin Stories of the Patient” whose “name, from the Latin, from the French, is not rooted in pain but her ability to bear. To endure” (Four Quartets 231).

The formal virtuosity of the poetry in Four Quartets also demands attention. A tercet is a verse form characterized by words flowing like rolling waves. It can be hard to create a sense of flow in three terse lines of tercet. And yet, when it is done brilliantly and expertly, the form seems the most natural vehicle for emotion that is so violently turbulent that it can only emerge in the tightly controlled and sparse economy of the tercet or terza rima. Written intentionally as interactive, improvisational tercets (Four Quartets 24), Yusef Komunyaaka and Laren McClung’s excerpt from Trading Riffs to Slay Monsters parenthetically invokes the archetypal and foundational ‘call and response’ poetics of African-American experience, ancestor of jazz and hip-hop, and folds it firmly into the archaic classicality of the tercet form. Their polyglot call and response style of making song, making meaning, out of unspeakable horror, out of the tortures of the master’s house, is the linguistic underground railroad for the febrile, hybrid ‘visual’ that is the COVID mask: a polyglot, overdetermined, puffing, laboring response to utter precarity and uncertainty. Can the unknown familiar, the unseen addressee, laboring at some other plantation, hear me even there, and come to my rescue, even protect me? Komunyakaa and McClung might be asking in their intentional choice of the call and response form in responding to the grotesquerie of ‘a locked-down night sky’ (Four Quartets 36). Their choice of the tercet form reaches its thematic and metric apogee as a vehicle for controlled violence in describing those old ocean waves carrying enslaved humans packed like canned sardines to a living death in a New World (Four Quartets 32 ff.). In that weave of verse they resurrect the desecrated souls of BIPOC, the ‘many thousands gone’ still mourning the modern world birthed as blood and ejecta of colonialism and slavery, in “Look, I am hurting to go back to 1544/ When the Portuguese struck the heart of Africa/ & prodded souls on schooners/ down in the midnight hold for weeks/ across the Atlantic, to a New World,/ where oldest greed swallowed its own/ barbed tail, & centuries later we are/ here to question & leech the past,/ speaking bluesy elegies to the future” (Four Quartets 33).

This discordant core of meter and verse mirrors masquerade as just the hobbled form needed to ‘embody’ the history of slave trading, the middle passage, slavery, and the world they have “now built that is not the one man/ inherited. I mean, factory smog & filth/ yellow the horizon to reveal a broken skyline/ where birds reckon into the wrong direction/ There’s not a prayer that can undo the scythes/ taking down the forests, or the fires burning/ where bandicoots & kangaroos disappear in billowing smoke” (Four Quartets, 32-33). Which has, thereafter, built the world—ours, COVID’s—where “bats fly/ into a market & unleash nature’s wrath” (Four Quartets 33). And the following verses recall the paradox of masquerade: “Don’t worry, love, there’s nothing/ in the world of mirrors that is not you/ looking back. A sip of this or that reveals/ undying darkness we all keep hidden/ but hocus pocus can leave one bitter” (Four Quartets 34). These lines, where the voice addresses a lover, also address or serenade a society (still loved) of the masquerade—our own, after all—sequel to a society of the spectacle, that has brought masking back as necessary mode and metaphor for world-splitting crisis, the apt defining visual of a consumer capitalism built on habitual and intrinsic deception, including the silly, designer, or even still-slipping masks of COVID: declaration of intent to protect and potential to kill.

The motif of call and response also appears in A. Van Jordan’s “How You Doin’?”: “Calling and responding to this gesture/of seeing one another that, for once, won’t/ be forgotten with the noise of the day/ So, when I think of my encounters with others/ who are quarantined, sheltering in place/ social distancing to stay alive, I ask them/ and —is it possible? for the first time?/ I truly wanna know” (Four Quartets 212). Stephanie Strickland’s Jus Suum asks many of these same questions, raising a call to know “whether they be freemen … for a single moment” (Four Quartets 45), to which “One Sentence to Save in a Cataclysm” responds “Belief/ in/ the existence of other human/ beings as such is love” (Four Quartets 54).

Mary Jo Bang’s “The Present Now” is full too of anxiety for responsiveness, for connections and contacts turning bloodless during COVID, all identities in that poem having become proxies as in the letter ‘X,’ a placeholder for all actual living, flesh and blood people. Only the cantos of Dante’s Purgatorio that the poet/speaker is translating retain heft, flexibility, and animation in being not just ‘X,’ but ‘XIX’ or ‘XX’ or ‘XXXII’ or especially ‘XXVII,’ a reminder that poetic language and words—seen as stand-ins or symbols or representations for ‘the thing itself,’ for the underlying Heideggerian physical world, or even as masquerades for a supposed hard, immutable, ‘real’—maybe the only truth left in a world where one seems to live inside an endless covering, coughing up “Keatsian blood” (Four Quartets 61). This is a world where enforced isolation and sensory deprivation generate language like “I don’t know whether I’ll ever be able to go out into the world without risking death” (Four Quartets 62), quite re-spinning Jean-Paul Sartre’s aporetic “Hell equals les autres” (62). This poet/speaker’s fallback dictum that ‘the dead don’t suffer” itself takes on a whole new valence when the living are buried inside COVID masks, the walls of one’s home, and the grief of seeing the faces of one’s loved and known ones vanish, become ‘X’—‘X’ suffices because what is identity behind a mask anyway?—is cousin to death or being in ‘Purgatorio.’ Bang’s emphasis throughout “The Present Now” on Dante’s Purgatory XXVII—a known disquisition on lust turning into care/love— casts new light on what COVID has done to humanity in its advent as a new memento mori, reminding us of what really matters: care/love above lust. In that canto, to describe that transformation, Dante uses the metaphor of goats frisky at noon becoming pliant and tired at sunset—goats famously being emblematic of unbridled lust suggesting Trump is that goat, the ‘craven’ creature concerned with lust—for what’s needed is the shepherd who offers care/love rather than lust, and instead “the country is being run by someone so craven” (Four Quartets 65).

Indeed, the days of COVID can be described as days when “thoughts against thoughts in groans grind” (Four Quartets 66; from G. M. Hopkins’ “Spelt from Sibyl’s Leaves”), as also days when the pressure of feeling one hasn’t “gotten much work done since, only what has to be done” (Four Quartets 66) looms over empty/crammed hours in all their paradox masquerading as coping. Yet, “What use to us are those meanings that don’t reach each other?” as Lee Young-Ju writes in “Guest” (Four Quartets 182)? So Ken Chen imagines refugee and migrant experience recently blazing across headlines of America and the world, speckled with ash from the apocalyptic social pandemic of hatred that necrotic political regimes have visited upon those bodies. Aptly calling it the ‘underworld,’ the Hades of Greek mythology, Chen describes the ‘illegal’ ‘alien/a/nation’ phenomenon thus: “Each passing day, the waves of Styx break new ground, spilling/ out/ national specters” (Four Quartets 92).

We need masks in case they save us; we need poetry because it saves us. In the face of the sheer enigma of the modern experience such as “We lived in giant tin eagles we used rags/ Wrapped around human bones as torches…” (“When Our Grandchildren Ask Us,” McCrea, FQ 85), we need poetry because COVID has proven that there are purgatories—pandemics of disease, racism and hatred—from which only poetry will save us, as Dante, or T.S. Eliot, whose own Four Quartets attempted many of these enigmas more than half a century ago, knew.

Poetry in the Pandemic is about having the iconoclastic, hard-hitting conversations about class, race, age, access, and privilege that COVID-19 has summoned up in the public sphere. The various inequities that drive and design our world when it comes to safety and security for the planetary and the human have been shockingly and painfully exposed in the firestorm of this pandemic, and in this astounding, brave and brilliant collection of poems, raging dissent against systemic and brutal racism forces open the doors kept solidly shut against full disclosure of systemic and historical privilege. The mask is a perfect device to draw attention to a hidden problem; it is a symptom and representation of imminent disaster that exceeds its physical format as a covering on single, individual faces, a flagging of ever-possible and ever-present collective, aggregate catastrophe. A mask is, in other words, a sign that betokens its utter inadequacy as only a sign. This is also what COVID-19 is: a clue that something is deeply, terrifyingly wrong with what we have done to nature, scientific endeavor, internationalism, humanism and humanitarianism. Poetry is the truth that unmasks that mask, as the impassioned poets of our time show us in Four Quartets.

—

Nandini Bhattacharya is a Writer and Professor of English at Texas A&M University. Her fields of expertise are South Asia Studies, Indian Cinema, Postcolonial Studies and Colonial Discourse Analysis, Women’s Studies, and Creative Writing. She has published three scholarly books on these subjects, the latest being Hindi Cinema: Repeating the Subject (Routledge 2012). Her first novel Love’s Gardenwas published in October 2020. Shorter work has been published or will be in Oyster River Pages, Sky Island Journal, the Saturday Evening Post Best Short Stories from the Great American Fiction Contest Anthology 2021, the Good Cop/Bad Cop Anthology (Flowersong Press, 2021), Funny Pearls, The Bombay Review, Meat for Tea: the Valley Review, The Bangalore Review, PANK,and more. She has attended the Bread Loaf Writers’ Workshop and been accepted for residencies at the Vermont Studio Center and VONA. Her awards include first runner-up for the Los Angeles Review Flash Fiction contest (2017-2018), long-listed for the Disquiet International Literary Prize (2019 and 2020), and Honorable Mention for the Saturday Evening Post Great American Stories Contest, 2021. She’s currently working on a scholarly monograph about how colonialism and capitalism continue to shape India’s cultural production, and a second novel titled Homeland Blues, about love, caste, colorism, and violent religious fundamentalism in India, and racism and xenophobia in post-Donald Trump America. She lives outside Houston. You can find her on Amazon, Twitter; Instagram, Facebook and her Blog.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)