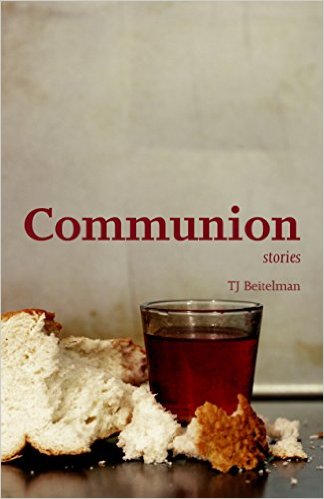

Black Lawrence Press, 2016

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN DUCKWORTH

–

“Most things don’t take root, and that is as it was intended.”

The above quote, a cryptic line from the story “Sister Blanche” in TJ Beitelman’s Communion, captures much of the magic and tragedy suffusing the collection’s stories—stories of marriages halfway ended, affairs partway consummated, vows only partially kept, and conversations only begun but never finished.

The full title of Beitelman’s new book is Communion: Stories, but that doesn’t quite describe the animal that is this book. While in places a reader may well be lulled into thinking they’re leafing through an ordinary short story collection, such as in “Antony and Cleopatra,” or “Joy,” other sections will lead to questions of genre. The early short pieces of the collection (“Artic Circle,” “Masks”) could be read both as prose poetry as well as flash fiction, testament to Beitelman’s lyrical dexterity as well as his strength at setting a scene and selling a mood. In a further departure, the book’s longest piece, “Notes on an Intercessory Prayer,” is less a story and more a lyric essay with brief fictional incisions into what is by-and-large a tribute to the late Benazir Bhutto. The last flush of stories (“Hope, Faith, and Love,” “Communion”) toward the end of the book can stand as individual pieces as well as chapters to a larger surrealist work that tells the myth of a working-class Messiah and the family he leaves behind without saving.

While most of the stories in Communion are set in Southern locales, their characters traditional (after a fashion) Southerners of working-class extraction, there are some notable exceptions. One of my favorites, “Yoi, Hajime” centers on a Japanese chicken-sexer reflecting on his time working in Atlanta, Georgia alongside a young black woman who he longs for but never gets around to courting. The model guiding most of Beitelman’s stories is less the lopsided pyramid taught in creative writing workshops around the country and more the asymptote: the curving line that draws closer and closer to the line that would be its mate without ever touching. The endings are often open-ended: pots left simmering on the stove. A wonderful example of this is the excellent flash piece “Blackface,” which leaves the reader with a powerful and pervading sense of mystification mixed with enlightenment as we see a drunken teenager break into a neighbor’s house only to come face to face with his own mother—naked and in blackface. The motivations are irrelevant, as are the consequences to the characters in the aftermath—all that matters is the powerful moment of recognition between the mother and son before the son flees the house.

TJ Beitelman’s Communion is not a conventional short story collection, nor is it the sort of collection that one could use as an easy, marketable model for putting together a first book. It is, however, memorable and equal-parts troubling, affecting, and inspiring.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)