96 pages, $18.00

Review by Carley Moore

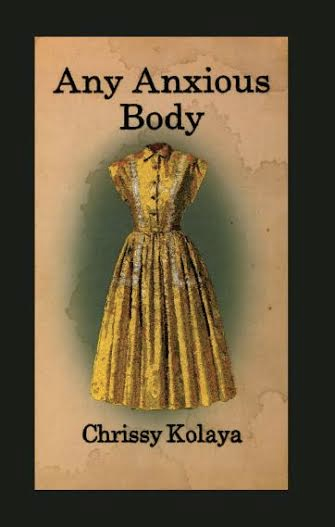

The cover of Chrissy Kolaya’s first collection of poetry, Any Anxious Body, is a drawing by Jess Larson of a yellow short-sleeved shirtwaist dress with a full skirt and white piping along the lapels and pockets. The dress floats in the blue and white watermarked background, as if on a dress form, inhabited by no particular body. Still, the dress is iconic and reminds one of the working-class American women in the 1950s who wore these dresses—mothers, aunts, grandmothers, wives, and girlfriends, all of them workers who tried to make a place for themselves as first- and second-generation Americans in small industrial towns. The dress is a ghost of sorts and the book haunts us, reminding us of the stories of love and loss, death and sacrifice, abuse and secrets at the center of family lore and history. Continue reading

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)