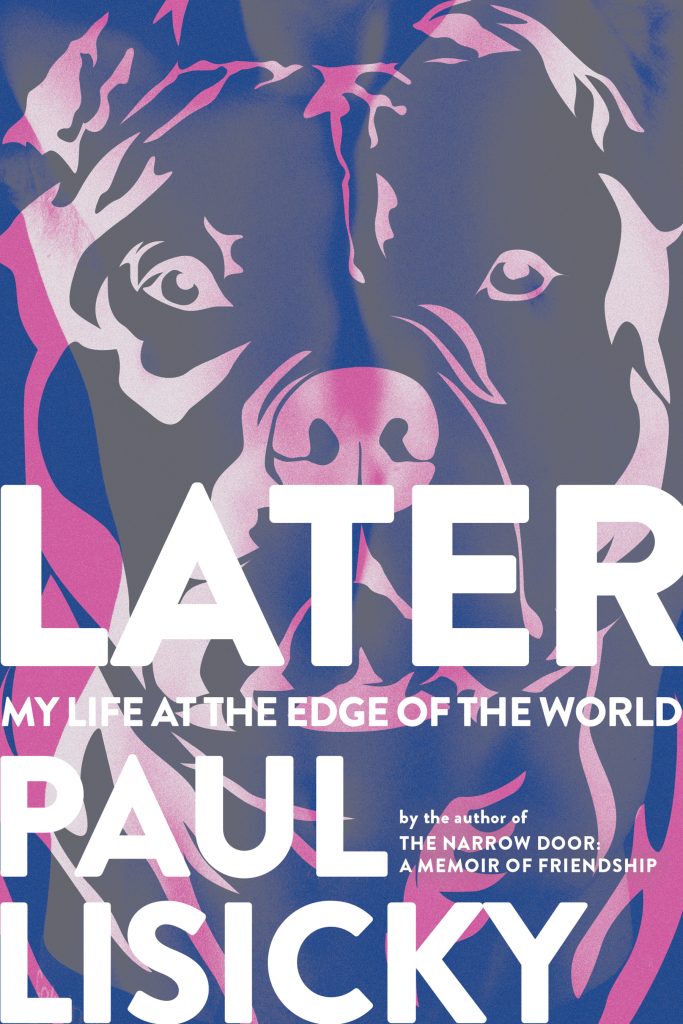

Graywolf Press, 2020

—

REVIEW BY DWAINE RIEVES

There are places we go to by choice and others where we simply wind up. The far tip of Cape Cod is, in Paul Lisicky’s new memoir Later, one of those places where your presence may only seem a choice. This captivating tale opens in the early 1990s, a time when the artists and writers in Provincetown, or “Town” as we come to know it, are constantly shadowed by AIDS. It is AIDS and the risk of the disease that, once you’re in Town, seems the ultimate decider. In the opening scene, we find a young writer arriving at the local arts center, his initial thoughts preoccupied with his family’s fears, especially his mother’s worry. “She is afraid of my living among my kind, especially now that so many young men are dying of AIDS. She is expecting me to die of AIDS.” It seems one’s fate in Town is one with AIDS, and the choice to live here—even if only for a year or two as a developing writer—is no cause for celebration.

A major theme in the early literature of AIDS was urgency. The poet Bill Becker titled his 1983 collection of poems An Immediate Desire to Survive. Immediacy was a warning, lateness no poetic conclusion. The journalist Randy Shilts constructed And the Band Played On along a timeline that leaves one breathless, the need to do something about this situation far too critical for anyone to sit and ponder. In Paul Monette’s memoir, Borrowed Time, the story races over only a few months. From the 80s until the mid-90s, the years for gay men were summarized in body counts, time always too short, science always lagging. Reflection, the ability to dwell in a place and contemplate this untimely world, was no unrushed option for a young gay man, that time-out simply inconceivable given the chase of the virus.

In Later, by contrast, we have a gift of time: a place for contemplation even as the shadow of AIDS still chases us. Such is the magic of living among the artists trying to create an art of life itself “at the edge of the world.” Lisicky writes, “Town moves on two tracks at once.” There’s the typical forward time and also “lyric time, which has nothing to do with the clock.” The residents of Town thrive on lyric time, this patchwork of images and actions they share with us in this luminous read. “It’s time as enacted in a painting or a poem or a song.” Lyric time is set up as the opponent of AIDS time. Lyric time allows us to sit with ourselves and think, for “lyric time moves off to the side and stalls: lateral instead of linear.” Lyric time in Later allows us to sit with the lives we’ve witnessed and will witness, including the lives within us. We flit with the narrator from lover to lover because flitting is all that this brief world allows us. We dwell with the one who seems to care. He moves on, and another steps up from the shadows. Or should, his arrival only a matter of time. Time is the beautiful lover luxuriating in the heart of Later.

Later also carries us from the years when AIDS seems inevitable for many gay men to 2018, a time when the risk for AIDS can be profoundly lowered and the disease itself treated. The narrative sweep in Later is linear, the inhabitants of Town faithful in trying to help the new arrivals find their own direction. These new residents have, after all, chosen this place where time and risks constantly mirror the body’s urges. Who we are, including our sexual nature, is a given, but where this nature might take us can be a choice. In Town, life itself feels a choice, the shadows close but also understanding.

The forward push of Later allows for detours. We are presented with the narrative in parcels, short sections that could be taken as patchy prose poems within each chapter with rich, challenging language. The structure of such finely stitched sections may easily remind you of a quilt, a collection of carefully stitched life stories, people and legacies to contemplate, the risks and rewards in where we choose to live, love, and in our all-too truncated time, develop. Not an AIDS quilt now in prose, not really. More a comforter as people in Town might stitch it, more purpose than opinion. In Later, we’re given the opportunity to feel deeply the places where we’ve been, the lives in which we now find ourselves, and the places where we must yet go. Later gives us time to suffer and also create, a place to comfort ourselves in our choices.

—

DWAINE RIEVES was born and raised in Monroe County, Mississippi. Following a career as a research pharmaceutical scientist and critical care physician, he completed an MA in writing from Johns Hopkins University. His poetry has won the Tupelo Press Prize for Poetry and the River Styx International Poetry Prize. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Baltimore Sun, Virginia Quarterly Review, The Georgia Review and other publications.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)

Indeed, the letters discussed by Cooke suggest to me that Pizarnik’s correspondence to Ostrov may have been manipulative, though, to what end? The letters leave the impression of a playful girl, and Enrique Vila-Matas, writing in Lit Hub in 2016, states, “The dark force of her Immaturity produces an irresistible attraction,” different from today’s “academic lyric poetry.” Pizarnik had a history of rebelling against the academic establishment, a characteristic that she shared with the Expressionists. But The Last Innocence/The Lost Adventures, collections written before her residence in Paris (1960-1964), has more affinities to Surrealism as compositions representing the poet’s unconscious psychological states of being and deep motivational drives (e.g., epigraph poem).

Indeed, the letters discussed by Cooke suggest to me that Pizarnik’s correspondence to Ostrov may have been manipulative, though, to what end? The letters leave the impression of a playful girl, and Enrique Vila-Matas, writing in Lit Hub in 2016, states, “The dark force of her Immaturity produces an irresistible attraction,” different from today’s “academic lyric poetry.” Pizarnik had a history of rebelling against the academic establishment, a characteristic that she shared with the Expressionists. But The Last Innocence/The Lost Adventures, collections written before her residence in Paris (1960-1964), has more affinities to Surrealism as compositions representing the poet’s unconscious psychological states of being and deep motivational drives (e.g., epigraph poem).