Little, Brown and Company

224 pages, $24.95 hardcover; $8.99 paperback

Review by Lisa Rabasca Roepe

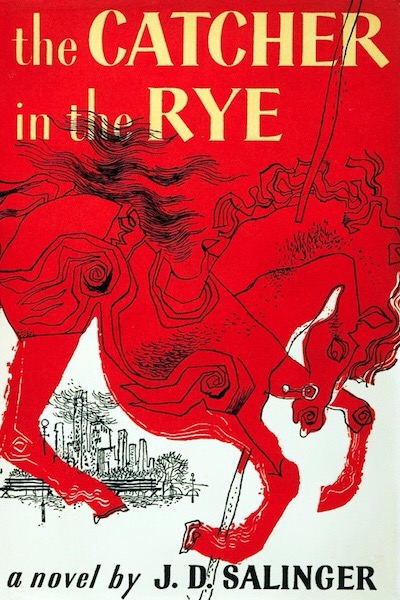

I first read The Catcher in the Rye when I was in high school and I was best friends with one of our class outcasts—a boy, much like Holden Caulfield, who was misunderstood, who was smart but yet managed to be failing most of his classes, and, like Holden, was kicked out of school. Although, unlike Holden, my friend’s departure from school was only a temporary suspension brought on by him setting a fire in the guidance counselor’s office in an ill-fated attempt to destroy a test he had failed miserably.

At the time, this book showed me it is OK to be an outcast, and Holden Caulfield, with his dislike of phonies and movies, and his concern for the ducks in the lagoon in Central Park South and his friend Jane Gallagher, became my hero.

The novel follows three days in the life of Holden Caulfield. Many have speculated that Holden is telling the story to a psychologist while inside a mental institution. “I’ll just tell you about this madman stuff that happened to me around last Christmas just before I got pretty run-down and had to come here and take it easy,” Holden says.

His tale begins on a Friday night, the weekend before Christmas break, and just after Holden has returned from New York City with the fencing club. The team had to forfeit their meet because Holden, their manager, left all the equipment on the subway. We also learn that Holden has been kicked out of Pencey Prep for failing every class except English, and it’s the third school he’s been asked to leave. His history teacher, Mr. Spencer, asks Holden if he has any concerns for his future. “Oh, I feel some concern for my future, all right.” Holden says. “Sure. Sure, I do. But not too much, I guess.”

Holden goes back to his dorm room and goes to the movies with friends, even though he hates movies. It seems like a normal Friday night on campus until his “handsome roommate,” who is on a date with Holden’s friend, Jane Gallagher, comes back to their room. They get into a fight and Holden decides he’ll just leave school early, go to New York City, check into a hotel for the next three days and then go home.

Over the next three days, we see Holden struggle with loneliness and depression (“I was feeling sort of lousy. Depressed and all. I almost wished I was dead.”) Eventually he sneaks home to see his sister, Phoebe, and leaves a note for her saying that he is moving out West and asking her to meet him at the Natural History Museum so they can say goodbye. Phoebe shows up with a suitcase and says she is going with Holden. Holden’s story ends with Phoebe on the carrousel and Holden standing in the pouring rain watching her and crying because he was “so damn happy.”

Since high school, I have probably read this book a half a dozen times. I have devoured everything else by J.D. Salinger—Franny and Zooey, Nine Stories, and Raise the Roof Beam, Carpenters—at least twice. I feel the same way about books as Holden does, “What really knocks me out is a book that, when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it.”

When I was younger, I wished I could have called J.D. Salinger and discussed Holden with him and told him about my friend who reminded me of Holden. I wasn’t aware of J.D. Salinger’s history with young girls and, in fact, I didn’t know about it until I attended the University of Iowa Summer Writing Festival and our teacher had us study For Esmé—with Love and Squalor. A few of the students were offended and refused to read or discuss the piece. I remember being annoyed with them because I just wanted to learn how to write like J.D. Salinger. Who wouldn’t?

It wasn’t until last year when I read My Salinger Year by Joanna Rakoff and Salinger, the 720-page biography by David Shields and Shane Salemo, that I started to feel creeped out. The story of how a 53-year-old Salinger wrote a letter to Joyce Maynard after reading her article, “An Eighteen Year Old Looks Back on Life” in The New York Times makes me uncomfortable, especially since she dropped out of Yale to move in with him. Maybe she wanted to learn how to write like him, too.

But I can’t turn my back on my one of my favorite literary heroes, Holden Caulfield. The Catcher in the Rye is a book that, regardless of its author’s life, I just can’t quit.

***

Lisa Rabasca Roepe is a freelance writer living in Arlington, VA. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Mid, Mommyish and Good Housekeeping.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)