(Marsh Hawk Press, 2018)

REVIEW BY JOAN GELFAND

—

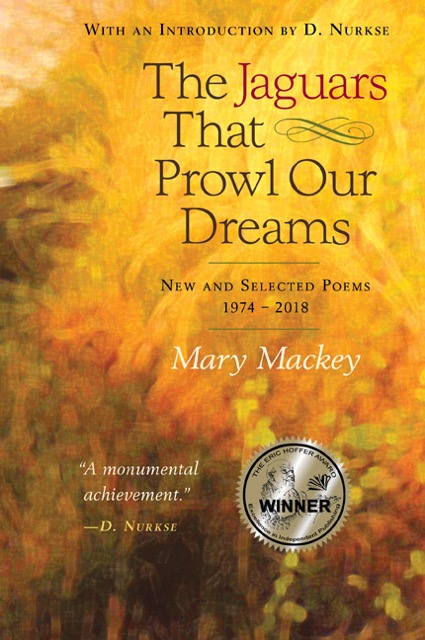

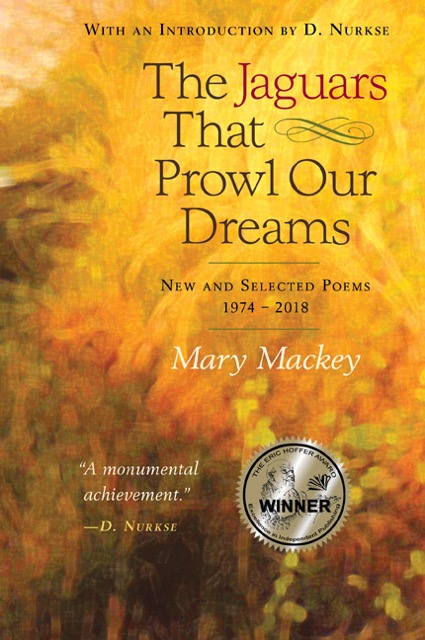

Having just won the Eric Hoffer Award for the Best Book Published by a Small Press in 2019 and a Women’s Spirituality Book Award, The Jaguars that Prowl our Dreams: Collected Poems 1974-2018 is a stellar work. In the span of forty years, Mary Mackey has published 14 novels, most with big five publishers (two under the pseudonym “Kate Clemens”) and eight collections of poetry, one of which, Sugar Zone, published by Marsh Hawk Press, won her the PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Award for Literary Excellence.

Added to these accolades, two of Mackey’s quirky and sensual poems from the series “Kama Sutra of Kindness” (Travelers With no Ticket Home) were featured on Garrison Keillor’s The Writer’s Almanac. All this was accomplished while teaching Film and Creative Writing at California State University Sacramento for over thirty years.

Mackey is a magnificent thinker with broad passions: pagan cultures, literature, anthropology, ecology and history are subject explored in “Jaguars.” After graduating with her PhD from The University of Michigan in 1970, she arrived in Berkeley, California, and began publishing in earnest. Her first novel, Immersion, was recently re-released. An ecofeminist novel, which takes place in the jungles of Costa Rica, it is a portent of climate change.

Serious topics such as ecofeminism, history, and ecology might sound dry, but like many magnificent thinkers before her, Mackey is in full possession of a wild and wacky sense of humor that always puts her readers at ease. I’ll also say here that while her mind is magnificent and her interests broad, her work, while stunningly layered, is always accessible.

I first fell in love with Mary Mackey’s poetry when she arrived at the open mic at the Gallery Café (San Francisco), a series that had a reputation for attracting exceptional poets. Mackey’s vibrant jungle imagery mixed with her confident and mellifluent Portuguese enchanted and enticed me to learn more about her work.

From Sugar Zone:

“Eles estão comendo they’re eating

purple snails powdered viper venom

lagartas esmagadas flowers that dye their lips

the color of blood singing of cities of blue glass

and the jaguars that prowl our dreams”

We are not in Kansas anymore, I whispered to myself. Or even San Francisco. It was thrilling.

As I became increasingly familiar with Mackey’s new collection, I was beguiled, awestruck and amazed at her ability to embrace the beauty of the world while being able to hold the frighteningly challenging, particularly in Brazil where real and present dangers were omnipresent. Rather than recoil, Mackey remained alert to the terrors and danger, external and internal threats:

“Sempre me amendrontou I have always

been afraid tankers strung out along the horizon

like a necklace of black

seeds a idéia de ter um filho of the idea

of having a child let’s get drunk

on cachaça forget her outstretched

hands her face the delicate angle of her nose

Mackey allows anxiety its full due, asking questions with no answers, setting down posits that lead nowhere except to more difficult questions.

tell me why they are burning

palm trees on the road to the airport

why the water tastes like ashes

why the windows of the cars are blind?

(Sugar Zone)

As a poet and reviewer, I had spent time researching Elizabeth Bishop’s source documents at Vassar College. In my essay, “Elizabeth bishop’s Alternate Worlds,” I explore Bishop’s development as a poet and novelist and the work she did before and after her experience in the Brazilian jungle.

I had delved into the boxes of archives guarded by the college where the young Bishop had studied and been taken under the wing of the well-connected Marianne Moore. As I worked, I began to make connections between the two poets.

Connections yes. But I want to make something clear before we go too far down the road: Bishop’s visions that resulted in a series of mystical and magical poems were inspired by experiences in the Brazilian jungle with ayahuasca – a half century before the hallucinogenic substance became a household word. Mackey is, and has always been, stone cold sober.

From the poem: “I Went to the Jungle Seeking Hallucinations”:

“I drank nothing I ate nothing

yet the fevers made me prophetic”

The daughter of a medical doctor, her experience with “an alternate world’ and visions began at a young age with an unfortunate predilection for running dangerously high fevers; an experience which terrified her parents but gave her the first opening to another reality.

From “Breaking the Fever”:

When I was young

fevers were attacked

the grown-ups would rub you

with alcohol

wrap you in wet sheets

refuse you blankets

fan you, feed you

plunge your wrists in cold water

In this poem, we have the entry into the world of a child disabled by illness in the form of a ravaging fever. Mackey uses a fine, but almost sickly rhythm here that telegraphs that this forced bed rest is just the beginning of the saga. Using recombinative rhyme (echoing/ wrap you, refuse you blankets, fan you feed you), we are in unflinchingly dire territory that is about to get worse:

“…At 105 I would start to hear voices

soft and lulling

at 106 faces would appear

swimming around me

stretching out their hands

they would gesture to me

to join them

I was always very happy then

floating out on the warm brink

of the world.”

No ayuhuasca required.

The second and third pages of the poem are absolutely magical, but it’s a spoiler if I tell you where this poem goes.

Whatever the outcome of that 106-fevered experience, one thing is certain: it opened Mackey to a world she could live with, so that years later, when she is struck in the Amazon jungle, she maintains the strength and presence of mind to pen another brilliant poem. For example, in her recent poem “105 Degrees and Rising,” Mackey writes that fever:

‘lifts [me] from my bed/in an ascending spiral /whispering my name over and over”

If what comes before prepares us for what comes next, Mackey has been prepared as a child by those fevered visions, once striking in the safely of her parents’ home, now striking in the far away, primitive jungle. In both cases, she hangs tight.

It is in the “Infinite Worlds” section of Jaguars that Mackey begins to let loose with imagery that is memorable, remarkable and absolutely frightening, but always adhering to poetry’s rules and codes and aesthetically pleasing in the darkest ways:

From “Ghost Jaguars”

by day you told us the dead crouch in the jungle

arms wrapped around their knees

heads down blind

living in a great blueness

that expands to the horizon

like an infinite ocean

at night, they rise

and hunt ghost jaguars

drink the black drink

fuck the trees

If you allow yourself to see this collection as a metaphor, I would suggest it depicts a poet drawn to fire, to destruction, and to experiences so intense they force you to question your life, your priorities and your raison d’etre.

It is true that, for many writers, the edge is where they feel most vital and at one with themselves. Take the journalist Marta Gellhorn, who craved war coverage as much as Hemingway needed to fish or Neruda needed his political disruptions and protests. But unlike an Ezra Pound, or a even a Carolyn Forche, there is never a sense of judgement or partisan politics in Mackey’s work. The poems stand on their own.

And then there is the figure of Solange, a figure Mackey first introduced her readers to in her award-winning collection Sugar Zone. Solange appears repeatedly through out Mackey’s later poems. Is she real? A lost friend? I don’t know, but I do believe that if Mackey had not been opened to an alternative reality early in life, Solange, the mythical and magical creature, could never have manifested.

Here is a recent poem in which Mackey introduces us yet again to this alter ego/goddess/mythic figure:

“Solange in her Youth”

sometimes you froze among the briars

deaf to our pleas to come back to the boat

froze as if you were listening

to a great slow rush of water

that would someday bear you away

I identified Solange as a spirit sister, and I love her, and I think in many ways, Mackey must love her too. Take for example, this excerpt:

“for a whole week, I missed Solange

Por uma semana eu tive saudade….

for twenty minutes I

stood in the deserted street . . . looking

for something

no longer there”

This progression of an image from book to book is exactly the beauty of a collected work: It engenders analysis; it gives readers the chance to discover how a poet arrived at point c from point a. It is, in its best form, a roadmap of a poet’s oeuvre.

Not all authors progress as Mackey has from her initial deeply personal to increasingly spiritual work. We don’t all go from the concerns of the immediate (career, partners) to thoughts of the world or to cultivating the ability to look at the wider world with compassion, patience and empathy. Not to mention, we do not all possess the mettle to position ourselves in the middle of a remote jungle where, given our proclivity toward fever, we would likely face another bout of illness.

Reporting that Mackey has progressed from personal to global is not meant as a blanket laudatory statement. Mackey is very much a product of her times, having started publishing in the 70’s when women writers were seeking to analyze their personal lives – the correctness of their politics, their sexual relationships and their career choices. One must remember that Mackey began writing her poetry just as an entire movement of women was breaking the chains of invisibility, just as entire classes of people today ache to break the chains of poverty, drug warlords and .

And for all of this poet’s serious looking, connection making, and reportage, Mackey is in full possession of humor; she takes life, but not herself, seriously. This humor puts us at ease. For example, I find it impossible not to laugh when reading “L Tells All,” Mackey’s rewrite of the myth of Leda and the Swan, reincarnated as a confession in a supermarket tabloid. Apparently, Leda’s relationship with Zeus did not go well:

“we had nothing in common

his feathers made me sneeze

I was afraid to fly

he was married

(of course

they all are)

we even had religious differences

This critique of a collection of Mackey’s best poems from a total of eight of her ten collections, leaves four collections I have not given their full due. To summarize: the early collections function as the foundation of Mackey’s magnificent mansion: we have a stand-alone section entitled “A Threatening Letter to Shakespeare,” and four previous book length collections: Split Ends (a deeply personal collection – 4 poems included) One Night Stand (3 poems on the topic of sexual politics,) Skin Deep and The Dear Dance of Eros 13 poems total on the topic of a young woman choosing to move through the world, the walls she hits, and the doors she pushes open.

Like the painters Gaugin, Picasso, Manet, this poet would never have found her rhythm had the early poems not been written. They are part of the journey and the training of the muscles of listening and opening, crafting and communicating.

And, finally, in 2018, along with writing new poems about the tropics, Mackey began to explore her Kentucky roots. These Kentucky poems form the section “The Culling” open the collection. Personally, these poems, as much as I support delving into one’s heritage and being transparent, are like an astronaut taking up gardening. It’s a fine pursuit, but we know that she must have the dream of space on her mind. These poems read like an addition to the family archives, an exposure of a painful roots, but they do not possess the same fully inhabited, magical, exotic and inspired worlds of the other collections. Perhaps because the information came down in family lore rather than immediate experience, they lack the same emotional investment, and even curiosity.

Still it takes a confident poet to lay down the tracks of a family whose matriarch was mangled by a hog, where guns prevailed, horrible catastrophes were common, and men were summarily valued over women. The hazard here, is that by opening with this series of poems, Mackey runs the risk that her readers may not not recognize the depth of her talent and the pyrotechnics she displays in her recent mystical poems and the award-winning books that have catapulted her to fame.

—

Author of “You Can Be a Winning Writer: The 4 C’s of Successful Authors” (Mango Press), three volumes of poetry and an award-winning chapbook of short fiction, Joan Gelfand‘s novel set in a Silicon Valley startup will be published in 2020 by Mastodon Press. Recipient of numerous awards, nominations and honors, Joan’s work appears in the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Huffington Post, Rattle, Prairie Schooner, Kalliope, The Meridian Anthology of Contemporary Poetry, Levure Litteraire, Chicken Soup for the Soul and many lit mags and journals. Joan coaches writers on their publication journey. http://joangelfand.com

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)