(Nightboat Books, 2018)

REVIEW BY ERIKA HOWSARE

—

If landscape is one of the primary wellsprings of poetic urgency, landscape design—the human intention that arranges ground, plants, walks and walls for the human eye—is a less common subject for poets. But there are numerous ekphrastic possibilities for a poet wanting to engage with nature, where nature is not untouched wilderness, but rather the raw material for a designer’s work.

Just as many nonfictionists have worked to untangle the relationship between the way we look at landscape paintings and our seeing of actual landscapes—Rebecca Solnit comes to mind here—a poet might find fertile ground, so to speak, in contemplating the way a garden design produces an experience for the visitor.

Cole Swensen has explored this question in more than one book, thinking about how we learn to see beauty and also how we physically, deliberately build our notions of beauty in actual places. “If you stare long enough the image / gilds itself over the eye,” she writes in Park, and again in Greensward: “…a garden is, in short, an open link bent on forming more, ever outward, a line between humans and other species…a following thinned to an horizon with all its attendant aesthetic principles of balance, rhythm, motion, etc., and the ethical principles inherent in them, and in both directions, i.e., it comes back to us.”

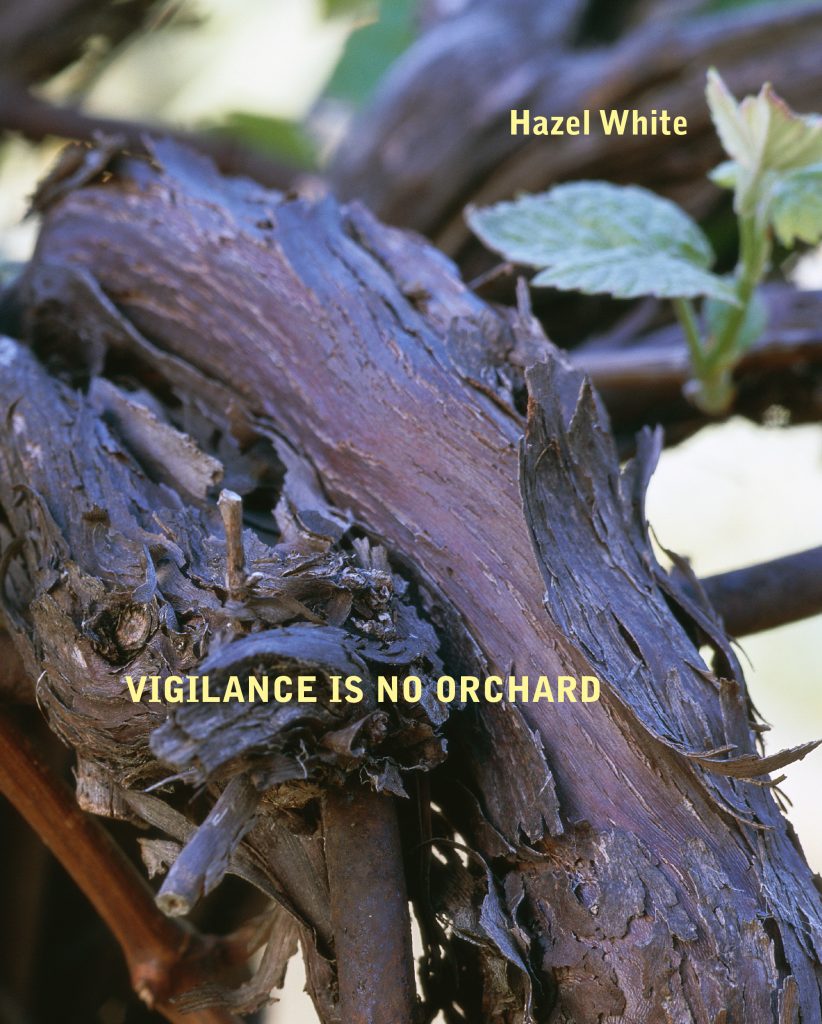

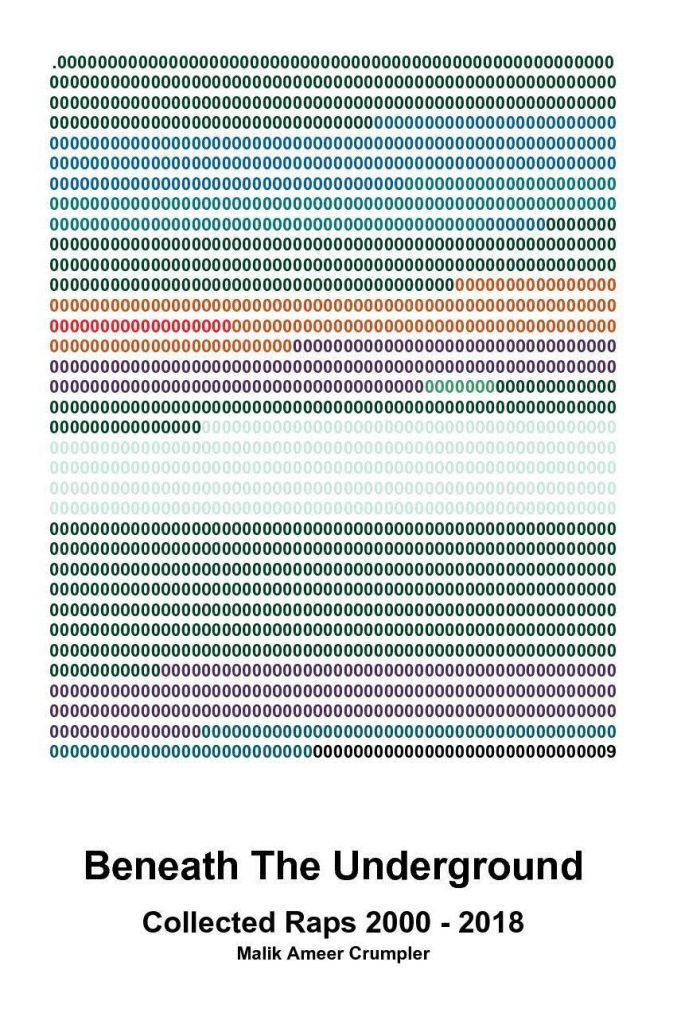

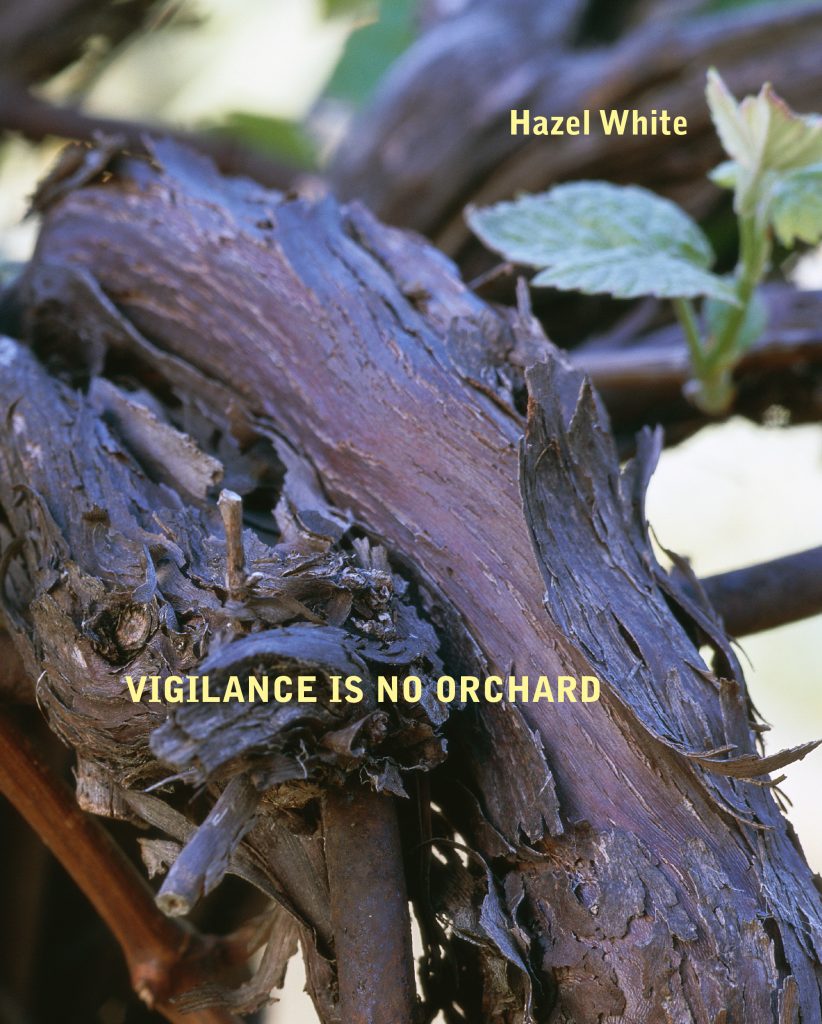

Poet Hazel White, in her new book Vigilance is no Orchard, takes the project a step further, to include the investigation of her own writing process as she grapples with the overwhelming aesthetic impact of a private Southern California garden designed by landscape architect Isabelle Greene. The book is much more than a simple account of walking through the garden; it includes quotes from conversations between White and Greene, and it repeatedly circles through a thicket of inspiration, influence, writerly ambition and writerly despair.

It’s worth knowing that White, along with one previous book of poetry, has published many instructional gardening books, and one can sometimes detect in Vigilance the tension between the experimental and commercial modes of writing—or, perhaps, a torque happily applied to the latter mode, as the poet begins to set herself free within the field of language, composing lines that would not rest easily in an average how-to book: “Terraces that step down gently were a clue that Greene intended a seamless departure. My feet anchored in groundcover, my head could ride the lines there, on / air’s back.”

But although White’s break with conventional language provides her with a lodestone and a methodology, the book’s true subject is her struggle with the admiration and envy she feels toward Greene’s accomplishment in the Valentine garden in Montecito. The garden is considered a landmark in modernist landscape design, but for White the source of unease is more personal and, indeed, bodily:

“I bowed low to Greene’s motion. Accepted the blow of it—I must know the how of its thinnest leaf on its strongest breeze, be sure, as my back was bending in astonishment.”

Being deeply affected by another person’s aesthetic accomplishment is a joy that immediately turns to exigency. “Beauty is not shelter, it necessitates a forward momentum,” White writes, in a perfect encapsulation of the discomfort that an artist can feel toward another artist’s work—the desire to produce a response that possesses, that wraps the original work in one’s own, even larger, vision. “…though the phrasing small and never named as envy: I would/I wished/I would/write about her.” Those final three words take on spatial shades—“write about” as in “encompass.”

The quest thus identified, White sets off (“urgently”) into cycles of poetic advance and retreat. Vigilance is a self-referential account of its own making that makes frequent use of Greene’s words to generate slippage between the landscape design process and the writing process. “To make a garden or a text show up—one needs the connections to be manifold,” writes White, and then quotes Greene: “‘But I hate geometry.’”

The writerly struggle, in White’s account, has many facets, and her commitment to an honest narrative about the difficulty of conceiving, and completing, a project is refreshing. Many of her readers, after all, will be poets who can intimately relate to the various conundrums she describes.

It takes White a while, for example, to settle into the scope of the project, to name all its imperatives. She must “have an environment whole…not parceling or steering into writing.” She must stay connected to her own physical experience in the garden: “Awareness of its forms alerts the body, so if I am quick / I can prod spatial pleasure for the texture of attention.” She must track inspiration as it “crosses into space never looking back,” like an exuberant toddler one must follow and contain without controlling too tightly. Above all, she must stay “at the edge inventing.”

“Drought / Worry of direction,” the title of the middle section in Vigilance, is of course a major part of the writing process: that parched, sinking feeling that the text one has been laboring over is ill-conceived and will add up to nothing. Drought for a garden is like doubt for the poet. “The work arcs and fails,” White assesses her own progress halfway through the book, and a page later, quotes Greene, who’s enjoying the fruits of a long and successful career: “My shows at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and the UCSB Museum were an immensely enlarging experience. There was ME!”

There’s another important difference, in White’s account, between her own struggle to create work that satisfies her and Greene’s seeming confidence, lightness, with the materials of her craft. Greene works with trees, rocks, water, “‘cow parsnips riffling among quaking aspens.’” She carries “‘a feeling for the crease in an arroyo, down in it and way back up the other side.’” This delicious physicality contrasts with the writer’s tools, which can only ever be abstract: “a fragmented narrative,” a plot that “dissolves to tableau…a gaze through glass toward no particular direction.”

Even the setting comes into play—White, who grew up in rural England, is permanently out of place in California, which is Greene’s native state. The oneness of Greene with her environment and its indigenous flora offset the sense of being a foreigner in another person’s vision.

White manages to report on these disparities between her own uncertainty and Greene’s artistic fulfillment in a way that is gracious and responsible, and makes clear that Greene is a warm, generous friend as well as an articulate commentator on her own work. Yet she also recounts at least one episode of questioning Greene’s aesthetic: “Wait– // Working low to the earth—is Greene timid and showing no tail?” White goes on to describe another, very different garden, one whose soaring verticals create an effect that’s more aggressive, almost violent (“Time Before whistles in from the outside. It…threatened to take down my pants”) compared with Greene’s horizontal, “explorative” or “solicitous” style.

This is not only the arcane shop talk of landscape designers; it echoes White’s own search for the right approach to poems. Elsewhere in the book she finds a parallel between the empty page (“White page a slick of construction talk”) and land that’s been violently cleared: “Scrape the hillside. / Loud bulldozer erases topsoil, turns, / piles it. / White real estate.” Even if the author isn’t punning on her own surname here, she does seem to be criticizing a certain mode of relation to a field of possibility.

A few pages later, a resolution suggests itself—a listening attitude, a way of allowing rather than forcing significance. “Move into mouth’s house: but don’t write myself into / a miniaturized shelter on paper.”

Physical reality, the garden itself and the body moving through it, are the keys both to White’s finding a way through her subject and to making this book an account of something more than a poet’s inner process—a real communication. The lines about the Valentine garden thrum with sensuality: “A field day, as wasps know, crawling split fruit.” And: “Brilliance of neon pink crabapple bloom / shatters around itself.”

Even as White suggests a parallel between conventional, strictured language and landscape design that imposes an external vision on a site assumed to be passive, she also echoes and reenacts Greene’s innovativeness, building a quiet rebellion against centuries of tradition surrounding nature poetry. The inclusiveness of her language makes clear that this voice belongs to someone who, though passionate about plants and gardens, is not writing from an idyllic vacuum.

That voice invites many kinds of language to become part of a search for “a manner in which language might push out and touch us.” Greene’s words, both quotes from conversations and bits of what must be written communications, form a collage with White’s deliciously unpredictable lines. The dominant mode recalls Mei-mei Berssenbrugge’s prose-influenced, abstracted style, but White is a collagist and a word-sculptor, who can deftly skid among registers, and

“pivot/

into

thinning

bruising

switch-

eroos.”

She has a keen ear for idiomatic speech and a designer’s eye for white space, and can slip between addressing the reader and seeming to address herself (“Try talkback…Make a rustle”).

The invitation to language-awareness parallels the call to place-awareness. One must be present to the presences (as Greene, quoted here, exclaims: “‘The persimmon tree is intensely red just this minute!’”) and mindful of imminent loss and decay (“Gardens flicker in and out of existence”). Being outside, being in a space, being attuned to one’s own body and conscious of the mind riding that body through a special, ordered environment: These are a salve for the condition of habitual thought and worn metaphor, a “coherent deformation” that acknowledges imperfection: “scars in the blue bloom of agave leaves.” These are the anchors that allow a new kind of language about nature to come into being.

It’s as though White strives to deserve, through writing, the experience she’s already had in the garden. The final chapter of this effort is ultimately not described, but rather manifested in the existence of the book itself, with all the moments of doubt, resolve, and labor elegantly woven into the work’s polished form.

—

Erika Howsare is a Virginia-based poet and her second full-length book, How Is Travel a Folded Form? was published this year by Saddle Road Press. She previously published a book-length meditation on waste, co-authored with Kate Schapira, called FILL: A Collection. She has also published several chapbooks and served as a coeditor at Horse Less Press for eleven years. Her reviews, interviews and essays have appeared at The Millions, The Rumpus, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and Taproot.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)